By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

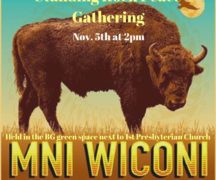

More than 60 people gathered on the green space in solidarity with the protesters, many Native Americans, trying to stop a pipeline at Standing Rock, North Dakota.

Megan Sutherland, who organized the gathering, said that the event was meant to show solidarity with the non-violent protests in North Dakota and with “an impassioned hope that together we can change our world for the better.”

The speakers at the gathering, though, said the conflict in North Dakota has resonance globally and locally.

Fawn Crawfoot

“These people are not victims,” said Bowling Green State University Professor Neocles Leontis, “”these people are fighting for all of us … fighting for our future, fighting for our children’s future.”

Rev. Mary Jane Saunders, from the First Presbyterian Church, noted how faith leaders have crossed sectarian lines to join together to protest the pipeline that traverses lands sacred to the Lakota.

Standing Rock has resonance in history and legend, and impacts into the future.

Chris Frye, who teaches at Bowling Green State University, connected the protests in North Dakota to the opposition of indigenous people from northern Canada to South America to large scale mining, lumbering and drilling projects that damage the environment.

That is further connected, he said, to the water problems in Lake Erie, Flint, Michigan, Lima and other places closer to Bowling Green.

Barbara Mann, a member of the Bear Clan of the Ohio Seneca and a professor at the University of Toledo, recounted Native American legends that prophesied the coming of Europeans and the devastating effects on native people as they moved westward.

Europeans wrote down these legends, she said, but what they didn’t write down was how it would culminate in environmental disaster.

Madeline Bengela, a student from the University of Toledo, gave a brief history of the Standing Rock protests. She noted that originally the plan called for the pipeline to cross the Missouri River upstream from Bismarck, but the white residents there protested, and the pipeline was moved upstream of the Lakota Reservation at Standing Rock.

The Lakota residents protested that the pipeline violated their treaty rights and crossed sacred land. Many Native Americans and others rallied to their cause.

They’ve been confronted by security and law enforcement using rubber bullets, pepper spray, concussion grenades and sound cannons.

Meanwhile, she said, the pipeline draws closer to the Missouri each day.

Macklin Becenti, a Navajo now living in Bowling Green, said he knew the value of water. He grew up with his grandparents. They didn’t have running water, so he had to fetch it every day.

In the 1970s Navajo protested the uranium and coal mining and oil drilling on their lands, he said. The government facilitated the projects that displaced natives and caused serious long-term health problems.

The Navajo, he said, are continuing to fight to keep their fresh water from being taken away and against the dangers of dirty water created by fracking.

Terry Lodge, a Toledo attorney, said Standing Rock is another battle in the “energy wars.” He is fighting the Nexus natural gas pipeline that will run through the area within a short distance of the Bowling Green water treatment plant.

He criticized a Bowling Green Board of Utilities approval of an easement through city property for the pipeline. (The easement must still be approved by city council; the resolution is scheduled to get a first reading at Monday’s council meeting.)

The pipeline is going through a particularly fragile geologic structure under the Maumee River.

Lodge said these local issues are connected to the continuing global conflicts including the war in Syria and the invasion of Iraq.

Leontis, a biochemist, tied the Standing Rock protest to global warming. “The only way we can keep temperatures within limits is if we keep fossil fuels in the ground.”

He told those gathered they didn’t have to go to Standing Rock. They could act locally.

He encouraged people not to bank with those institutions are financing the $4 billion Dakota Access Pipeline. He cited five banks that have a local presence – PNC, Citizens Bank, Chase, Bank of America, CitiBank and Comerica as well as the investment firms Goldman-Sachs and Morgan-Stanley.

He also urged people to take advantage of Columbia Gas home energy audits, so they use less fossil fuel.

BG City Councilor Daniel Gordon also said there are issues that can be addressed locally. He urged citizens to lobby city officials for bike lanes, community gardens and other projects that would make life better and more sustainable in the city.

“The reality is we are not passive bystanders unless we choose to be,” he said. “We can’t just sit back and expect others to do it for us.”

After the gathering a number of participants assembled to drape a banner down the I-75 overpass on East Wooster Street.

One of those was Brianna Drevlow whose family is in in Morton County, North Dakota. The pipeline, she said, was not just affecting the reservation, but also the water supply of nearby family farms.