By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Stop the Bleed started in the wake of tragedy.

The trauma surgeon who treated the victims of the Sandy Hook Elementary shootings realized that some of them could have been saved if someone had staunched their bleeding.

Stop the Bleed’s goal is to teach people a way to do just that the same way they are taught CPR and the Heimlich maneuver.

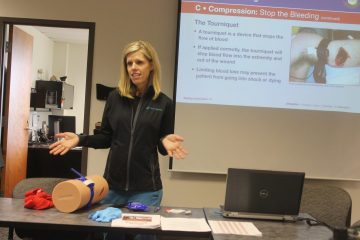

Nicole Knepper of Mercy Health explains compression

It’s needed not just in the case of a mass shooting or bombing. Victims of car accidents, job injuries or household mishaps could have their lives saved if someone can stop them from losing blood.

Nicole Knepper, who was at Bowling Green State University Friday to train campus police officers, said these techniques were used when her father-in-law was injured while cutting wood.

“We’re just giving people the knowledge to act immediately to save someone’s life,” she said. “You never know when this would be needed.”

Acting soon is essential, said Knepper, a training coordinator for Mercy Health.

A person weighing 150 pounds has about five liters of blood. Losing 40 percent will cause the person to fade into unconsciousness.

The two techniques to stop critical bleeding are applying a tourniquet and packing and compressing the wound.

Stop the Bleed provides kits at their website (bleedingcontrol.org), but common objects at hand can be used. A t-shirt and a pencil can be used as a tourniquet.

Even a dirty sock can pack a wound, Knepper said.

Stopping bleeding will save the person’s life. You can’t give antibiotics to someone who is dead, she said.

If possible though the first choice is a tourniquet. That marks a change in training. Knepper who has been a trauma nurse for 25 years said medical professionals were told never to use a tourniquet. The fear was that cutting off the flow of blood to a limb would result in the need to amputate the limb.

But there have been no documented cases of amputation from tourniquets on for less than two hours, she said.

In any event, she said, the approach is to save a life even if it means losing a limb.

Officer Clay Myers applies a tourniquet while Officer Daniel Polin looks on.

The tourniquet will hurt, a lot. Pain is not a reason for easing up or thinking it’s not on properly, she said.

But tourniquets cannot be applied to some areas, the neck and groin. That’s when packing and compression are needed.

Knepper demonstrated packing the wound with the hemostatic dressing. That dressing has a substance in them that promotes coagulation. Like other techniques and material promoted by Stop the Bleed, this was developed by the military to treat battlefield injuries. But other materials at hand can be used, she said.

The most difficult are wounds to the torso. Those usually involve internal bleeding that compression and packing cannot stop. Those victims should be the first to get treatment.

Knepper said that the training is kept to the basics, so people aren’t afraid to put it into practice. “You have that knowledge in there,” she said. “Once you take the class you have a sense of what you need to do.”

The important thing, she said, is just to stay calm.

Chief Michael Campbell said no particular concern prompted the training. The sessions are part of the police force’s ongoing schedule of in-service training. Half the officers were trained Monday, and the remaining 10 took part in the Friday session.

It was just one section of an all-day training on various topics.

Campbell said when he contacted Knepper, they discussed all the ways these techniques could be used. “It could be a violent shooter incident,” the chief said. More likely, though, it could be a traffic accident or someone injured while working on campus.