By Dan Skinner

Ohioans are understandably proud of the fact that their state was abolitionist from its inception. Predictably, this aspect of our state’s history has been evoked within the context of the anti-racist discussions of the past few months. I recently took some time to read David McCullough’s, “The Pioneers: The Heroic Story of the Settlers Who Brought the American Ideal West” — not exactly a “critical” history, as the title makes clear, but a book with much to offer Ohioans at this moment. The book, supplemented by a bit of poking around online, shows us the complexities surrounding race in Ohio’s founding.

First, the proposal to ban slavery in Ohio was very close, passing by one vote. This is just one reminder — as though we need it these days — that Ohio’s abolitionist identity may be more fragile than many Ohioans may be comfortable with. The enduring consequences of this identity was articulated nicely in a piece in Belt magazine by Eric Michael Rhodes, who reminds us that “Ohio has always had confederate apologists.” I will never forget seeing a Confederate battle flag flying proudly from the passenger window of an F-250 on the corner of Lane and Kenny the morning after Donald Trump was elected. It was a portent of things to come.

But what does the fact that Ohio’s anti-racist bona fides are fragile mean for the discussion happening right now about the signs, symbols, and names we display in prominent Ohio spaces?

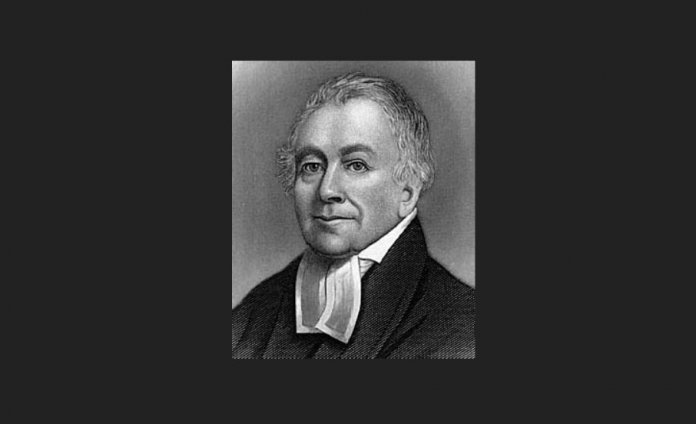

A second focus of McCullough’s book may provide an answer, and this concerns the importance of the Rev. Manasseh Cutler to Ohio. The Massachusetts-born Rev. Cutler played a central role in the establishment of the “Northwest Territory,” now known as Ohio. Cutler was a drafter of the Northwest Ordinance, the document that provided guidelines for admitting new states into the Union, including how rights would be determined within those news states. Cutler was well-known as an abolitionist whose son Ephraim advocated strongly, as an elected representative to the Ohio legislature in 1800, that Ohio should remain a free state.

Those versed in Ohio University trivia know that Cutler’s name was given to the building that houses the university’s president’s office, and is also the namesake of an important scholarship program. The restaurant at the Ohio University Inn is “Cutler’s.” The Cutler name is as ubiquitous in Southeast Ohio as Carnegie is in Pittsburgh. Cutler advocated for the establishment of Ohio University and was integral to its founding.

The Cutler connection to Ohio University is appropriate since, in addition to his abolitionism, Manasseh, and his son Ephraim, were stalwart champions of public education, the kinds of individuals that gave Ohio a national reputation for being a part of the expanding United States where public education would be considered a key to freedom and prosperity. The Cutlers were in many ways progenitors of a state that would soon be dotted with vibrant liberal arts colleges that were not only accessible to a wide range of Ohioans, but that were among the first to welcome Black students and women into the ranks of higher education.

Readers will surely guess that there is more to the story, however, and they would be right. Cutler was also a key player in the destruction of native culture and lands across the region. This will come as no surprise to anyone who has studied the founding of the United States since Ohio — like all of the West — was birthed in bloody conquest. The Buckeye State, like the U.S. itself, is the product of violent settler colonialism.

Curiously, in now-discredited coronavirus speech last week, Gov. Mike DeWine briefly glossed this history:

We must take the long view in a response to [COVID-19] and remember that Ohioans have always been a strong, determined, resilient people who time and time again have overcome adversity and beat the odds. From the Native Americans who created intricate and massive earth works. To the pioneers who navigated their way along the Ohio River and constructed the national road.

It’s unclear why DeWine saw fit to namecheck Native Americans in this particular speech. But when he did, he followed it up with a cynical nod to the pioneers who worked tirelessly to erase Native American culture from the Ohio territory. DeWine elided the more complicated history to make an uncritical reading of Ohio’s Native American history as part of his gubernatorial pep talk.

Even as we wrestle with the genocidal namesake of Ohio’s capital city, and the continued treatment of Native Americans as a mascot by a certain baseball team on the lake up north, reminders of this history are all around us. Even our state’s name was taken from the Iroquois word for “great river” according to some accounts. There are few Native Americans here, but lots of Native American words. These names stand as reminders that our state itself was carved from a history that still has a lot to answer for.

This destruction of the native cultures included the siting of Ohio University itself. Here’s an excerpt from Manasseh Cutler’s diary, which McCullough cites:

“This was a strange introduction of the higher classics to the Northwest. In a fleet of canoes, propelled by the power of the settling pole against the swift and narrow channel of the Great Hocking, accompanied by armed guards against the lurking savages, and carrying with them the pork, beans, and hard tack that made up their rough fare, the committee of old veterans of three wars proceeded to fix, with compass and chain, the boundaries of the University lands. There was little of culture and polish in the undertaking, but rifles, canoes, and salt pork were never put to a better use.”

In light of his role as a settler colonialist who fixed the boundaries of Ohio University by force at the beginning of the 19th century, what are we to do with Cutler?

I do not wish to enter into so-called “cancel culture” debates. I will note that my preference is that we simply do away with monuments and named buildings altogether, mainly because I find them mostly lazy and uncritical ways to engage history. But acknowledging that I am virtually alone in this belief, I want to argue instead that a different path is possible.

There’s been a lot of talk of late about “learning from the past.” I support this. But it’s not enough. Learning must be paired with policy action. If we want to continue to honor flawed, complicated founding figures, then we must lean in to their redeeming values. We must invest concretely in those values.

To return to Cutler, while we need to come to terms with his role in the violent settler colonialism that is a permanent part of Ohio’s — and Ohio University’s — history, we should also decide whether Cutler’s other values are worthy, on balance, of his redemption. In Cutler’s case, this would include not only his abolitionism — which he fortified against attempts to make Ohio a slave state — but Cutler’s stalwart advocacy of public education.

We can keep the Cutler name, which evokes Manasseh, but also Ephraim, who was an early Ohio University trustee. But we can rightfully do this only if we engage in another, more tangible project, not only to reckon with the Cutlers’ violent politics of dispossession, but in equal parts committed to funding an increasingly anti-racist public education system. Such anti-racist policymaking would position the Cutlers as the anti-DeVos, a counterweight to our scandalous current secretary of education who gives not a damn about the public education she is supposed to champion and who has worked at every turn to weaken the supports public education advocates had been working to put in place to support Ohio’s students and instructors. Ohio, a state that once took the lead in opening institutions of higher learning, must aggressively counterpunch DeVos’s attempts to weaken Title IX protections that have been so central to protecting women within higher education.

Cutler, like many men of his time, saw public education not only as a foundation for professional development and employment, as we too often do today, but a keystone of freedom. The American project, so-called, was dependent not only on more and more Americans being educated, but being educated in the specific mode of the liberal arts that so many of Ohio’s colleges once championed. That mode is under attack, by the Trump administration, of course, but also state leaders transfixed by feeding their constituents desire for the lowest taxes possible, while the education of our citizenry erodes. Leaders in higher education in Ohio publicly lament these erosions, but consistently fail to reverse it.

The colleges and universities that Cutler championed are now under attack and in decline. And things promise to get worse in coming months and years. State support for public education in Ohio continues to languish and higher education leaders seem largely resigned to merely do the best they can within the status quo. Their key tools are not advocacy and moral indignation, but programming cuts, layoffs and furloughs, and tuition hikes. COVID-19 has intensified attacks on the liberal arts foundations of Ohio’s colleges and universities, but it needs to be remembered that this was a process well underway before 2020.

Ohio can keep the Cutlers. But if we want to make good on this moment of renewed social justice commitment, policymakers need to think about polishing up the silver linings of people like Cutler so we can think about what it means to celebrate them in a way that is consistent with the values we claim to champion today.

Dan Skinner is Associate Professor of Health Policy at Ohio University, located at the Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine’s Dublin campus. He is the host of Prognosis Ohio, a health care podcast affiliated with Central Ohio NPR-affiliate WCBE. Follow Dan at @danielrskinner.