By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

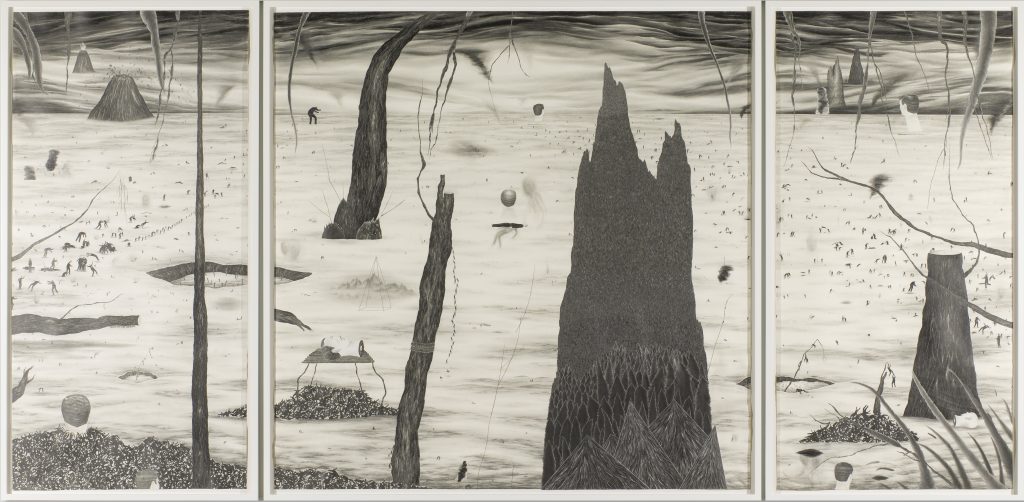

Walking into the gallery at the Toledo Museum of Art, the viewer is confronted by a three-panel scene. At first with its majestic mountains leading to a snowy bowl, it looks like a ski resort. Further study shows the tiny men, all decked out in matching sweat suits and sneakers, are not skiing. They are engaged in some vague approximation of calisthenics. The eye is drawn in, the dozens of tiny men, now are hundreds at least. While they could be anonymous – though their faces are distinct, the wildlife, that emerges as the gaze settles into the scene are drawn with more distinction. Off in a corner, two of the men study with blank intensity a dead deer. It’s all a mystery to them, and to the viewer. Why are there two World War II bombers approaching over the mountains?

Robyn O’Neil’s “Everything That Stands Still Will Be at Odds with Its Neighbor and Everything That Falls Will Perish Without Grace” offers an introduction to “Telling Stories: Resilience and Struggle in Contemporary Narrative Drawing” at the Toledo Museum of Art. The show is on exhibit through Feb. 14.

The show includes work by O’Neil, Amy Cutler, and Annie Pootoogook.

“I brought all these artists together because I’ve been aware that drawing is having this resurgence for the last 35 years,” said Robin Reisenfeld, the museum’s senior curator of works on paper. “It’s been extremely popular with contemporary artists, and so one of the goals of this exhibit is to really show the vitality of contemporary drawing and its global reach, its international stature and scope and how experimental it is and how accessible it is.”

O’Neil and Cutler explore fantasy worlds of their own creation – one populated only by men, and the other populated only by women.

‘Myself in Scotland’ (TMA photo)

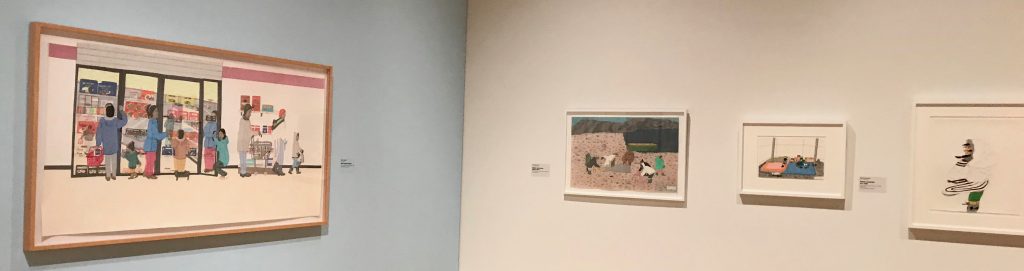

Pootoogook documents her homeland in Kinngait (formerly Cape Dorset) in Nunavut region in the Canadian Arctic. While O’Neil and Cutler create their worlds with fine lines, Pootoogook’s work seems almost child-like on first glance, before revealing the close observation of contemporary Inuit life.

O’Neil’s vision for her other world arrived on the scene at the 2004 Whitney Biennial. Eight years later what started with “Everything That Stands Still Will Be at Odds with Its Neighbor and Everything That Falls Will Perish Without Grace” ended with the more bluntly titled “Hell.”

O’Neil was raised a Catholic, and her work bears the influence of the work of northern Renaissance, including the work of Hieronymus Bosch.

“Hell” includes 65,000 figures engaged in all manner cruelly, including rape and murder. She uses collage to add larger severe heads that haunt the landscape. A volcano spews human forms. An ominous dark tower dominates one side of the landscape. It is constructed of tiny monks, each one hand-cut.

O’Neil grew up in Nebraska, and her closeness to nature and concern about the environment emerge. Once she’d killed off all her little men, she has turned her focus on the natural world, which proves as fierce and unforgiving as her imagined world. The artist expands her palette to include colored pencil and acrylics as well as graphite.

The exhibit includes an animated film that tells the full story of the rise and fall of this sterile, male world. Her notebooks, which chronicle her work, are also on display.

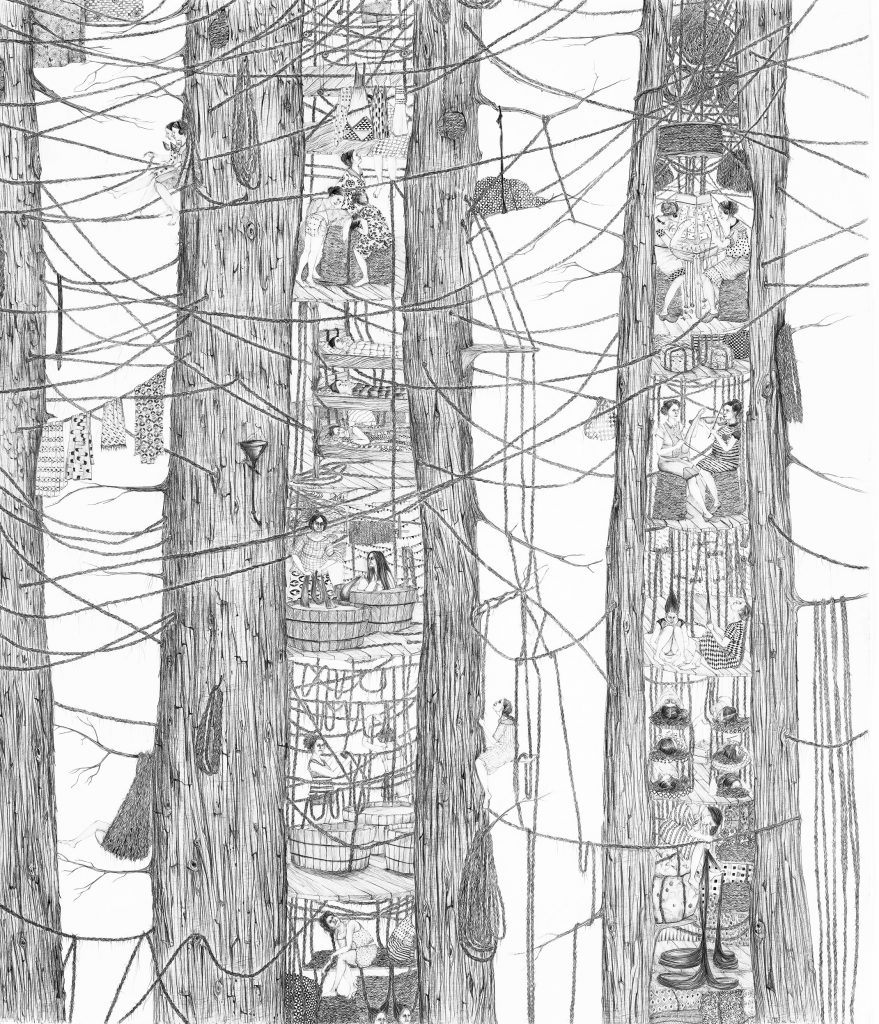

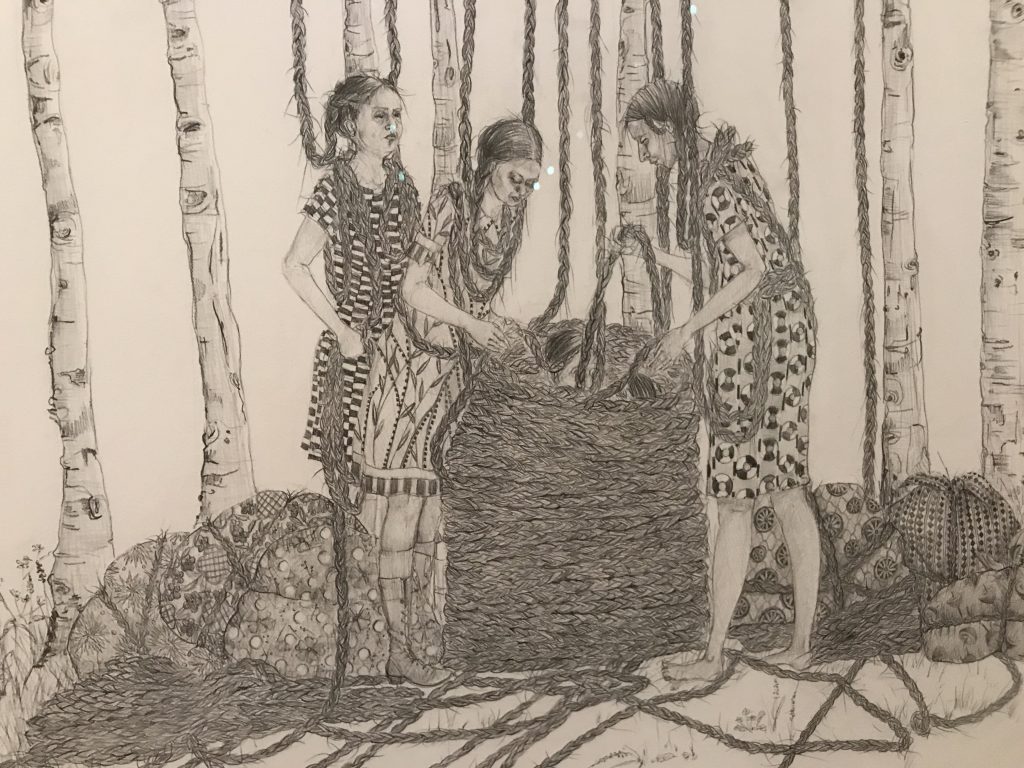

Cutler, like O’Neil, uses a simple pencil to create complex finely detail scenes.

Cutler depicts a self-sufficient community of women who live and work in the hollows of trees. They perform simple tasks that revolve around the principal product of their society – hair. Bounteous, flowing locks, that spill through their lives. It is the basis for their economy, Reisenfeld notes. They fashion it into ropes, from which their beds hang. They weave the hair. The hair is a medium of communication.

“Her depiction of space doesn’t make any sense,” Reisenfeld said. “It’s not supposed to, but it does.”

She references Persian and Japanese motifs as well as illustrations for 19th century folk tales.

“Amy’s work, I believe, is a statement of how struggle is really a condition of female existence,” Reisenfeld said. “All of her women are engaged in these illogical repetitive tasks that act as a metaphors for what’s going psychologically.”

Pootoogook was a third generation Inuit artist. Her grandmother, Pitseolak Ashoona, was a pivotal figure in the development of Inuit design. Pootoogook includes a portrait of her, as well as a still life of her tools.

In one depiction of a family camping, she evokes a drawing, “Sleeping with Ghosts,” by her mother, Naoachie Pootoogook,

Annie Pootoogook made her mark by turning away from a focus on the traditional. “She’s extremely important because she was one of the first Inuit artists to dispel the stereotypical notion of Inuit life being tied to the past and being untouched by the outside world,” Reisenfeld said.

Her career was brief. She emerged when she won a major Canadian art award in 2006, and her work was included in the international exhibit Documenta.

Pootoogook died in 2016 under suspicious circumstances.

In “Dr. Phil,” the central figure is sprawled on the floor of a spare home watching Dr. Phil, outside the viewer can see the utilitarian Quonset hut-like architecture, and snowy landscape. Inside the spare room, Pootoogook details the connections to the outside world.

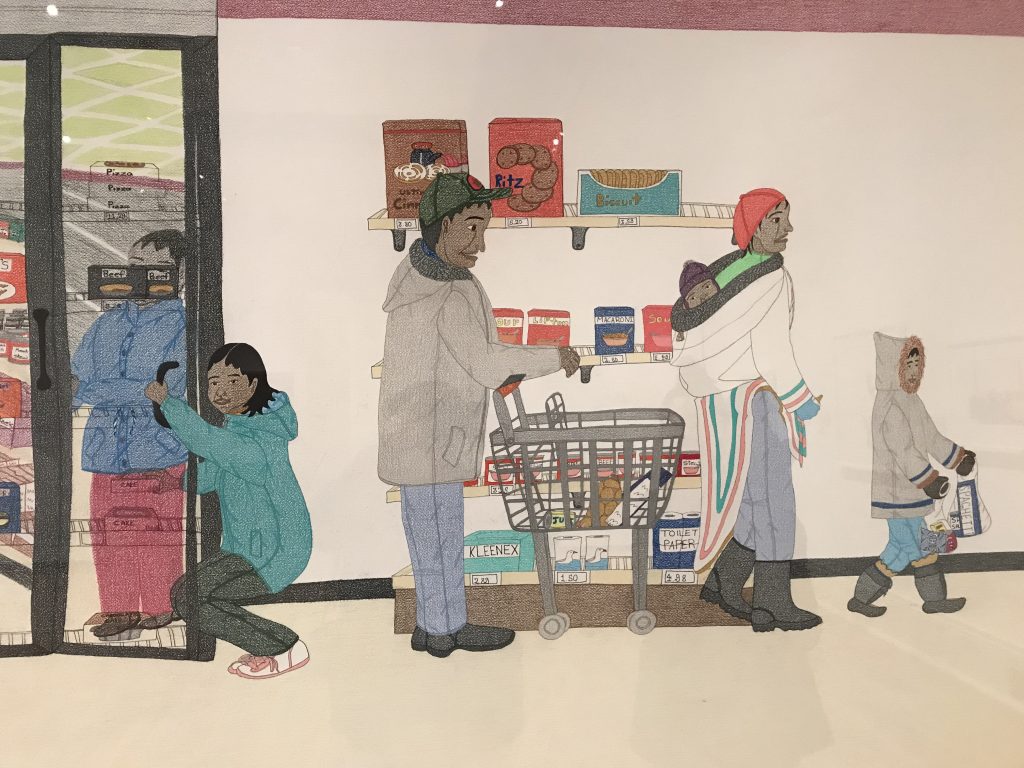

Across the back wall is one of her largest pieces, “Cape Dorset Freezer,” a scene of people shopping. There’s an irony of the artificial freezer having a place in a frozen landscape.

Pootoogook makes skillful use of reflections. Some of the goods in the case are brand names, others are simply labeled like those multiple containers of fries. While most of the figures are dressed in modern parkas, one woman is wearing a traditional amauti, a garment designed so a baby rides in the hood.

That speaks of a tradition not in conflict, but co-existing with contemporary life.

“Telling Stories” does much the same. Drawing is at one utilitarian and artistic, and dates back to our prehistoric ancestors drawing on cave walls. That spirit still resonates in the work of Pootoogook, Cutler, and O’Neil even as grapple with the concerns of modern existence.