By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Like most of his fellow Americans, Warren E. Hunt wanted to forget the Vietnam War.

“You don’t want to think about it. You want to be done with it.” That was his attitude when he returned to Toledo after serving a year as a communications specialist in South Vietnam.

The war wasn’t done with him though. “It doesn’t go away,” Warren, 70, said in a recent interview. It dogged him. The memories of what he experienced would surface at “inappropriate times.”

“I was depressed a lot,” he said. “I never thought it was because of the war. I never put two and two together.”

In Vietnam. (Photo provided by Warren Hunt)

Warren came anxious to pick up where he’d left off when he was drafted in 1967. He was going to spend some time at home in rural southern Michigan where he grew up, and then attend the University of Toledo on the G.I. Bill.

He did that, and went on to get a graduate degree in German. He wound up teaching German at Bedford High in Michigan.

Still the war was always there. “I just wanted it to go away. I didn’t think about it a lot until it was intrusive.”

It wasn’t until later that he grasped the fact that “I had lived an entire year in a hostile environment where my life could have been extinguished at any moment.”

Hunt confronts that experience in “Reflections on the Vietnam War: A Fifty-Year Journey” published in 2017 using CreateSpace Publishing. A part of “Reflections” was published in a special section put out by USA Today..

Hunt will read from the book Monday, May 14, at 7 p.m. at Grounds for Thought, 174 S. Main St., Bowling Green.

The book was prompted by a high school assignment. His goddaughter, Meghan Cremean, was given an assignment in high school to interview a Vietnam War veteran in 1998. She turned to Hunt. That planted the idea of his writing more extensively about his time in Vietnam. Then while attending a Memorial Day Service in 2014, the thought came to him: “It’s time.”

He’d done a lot of writing for his academic studies, and even had a few poems published in The Collegian at UT. Aside from that he hadn’t written much.

He struggled with the form the book would take: A memoir? A narrative?

Hunt said the problem was that his memories were fragmented and insufficient to support a continuous story. So he turned back to Meghan’s 1998 assignment. He decided he’d write the book as extended series of answers to her queries.

The result is a portrait on one soldier’s time at war set against a historical backdrop delivered in clear, straightforward prose. He gives a sense of the mundane as well as those vivid moments of terror.

Hunt explains that as a teenager he supported the war, buying into the argument that the Communists had to be stopped in Vietnam. He didn’t buy into it enough to enlist, instead he was drafted. He had been accepted at Bowling Green State University, but questioned his readiness for college.

He ended up in the First Infantry Division, the “Big Red One,” serving in the 121st Signal Battalion. He was in country from July 1968 to July, 1969. Two months of that time he was stationed at Quan Loi, near the Cambodian border, where the North Vietnamese were bringing in troops and supplies.

Though Hunt didn’t go out on patrol, the base camps were regularly shelled by Communist artillery and mortars. Still he’s aware of the greater risks faced by “the legs,” the infantrymen who went into the jungle.

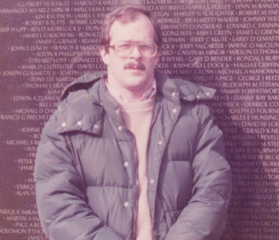

At the Vietnam War Memorial in 1982. (Photo provided by Warren Hunt)

This was life in the Vietnam War. No frontlines. Instead U.S. troops “surrounded and outnumbered.” Hunt and his fellow soldiers would be rousted from their beds to guard the perimeter in case the Vietnamese Communists decided to attempt to overrun the camp.

He said dozens of men were killed at the Lai Khe base camp in his 10 months there.

Hunt’s experience of the war changed his outlook on it.

He grew to believe that it was a “foolish” enterprise from the start and doomed to fail.

The South Vietnamese government was inept and corrupt. The North Vietnamese and their southern allies, the Viet Cong, were patriots fighting to rid their country of foreigners. “For them it was victory or death,” he said. “I could go home.”

Even if the United States population had been behind the effort, which it wasn’t, the war was an impossible venture. “We would have had to destroy every inch of the country and killed everyone.”

Hunt acknowledges that there “are vets who don’t want to hear that.” And, he said, he would never argue with them. Each person experienced and processes their service in their own way.

Coming back, he received mixed reaction. One guy bought him a drink in an airport bar. In a bar in Toledo, the bartender, a World War II vet, responded when told Hunt had just returned from Vietnam: “So what?”

Hunt was at UT when student protestors were killed at Kent State. He decided not to go to school for a few days afterward.

Even as his life seemed to follow a steady course, “not everything was quite right in my mind. … I couldn’t put my finger on it,” he writes.

He saw a flyer for a gathering of a new group, and so was in on the formation of the Toledo chapter of the Vietnam Veterans of America.

It was with his fellow VVA members that he traveled to Washington D.C. in 1982 to participate in the ceremonies surrounding the dedication of the Vietnam War Memorial.

He searched for and found the name of Francisco, who he’d seen blown to pieces back in Vietnam. He writes: “The shock, revulsion and sadness I had repressed all those years resurfaced in an onslaught of tears and inaudible sobs that lasted for several moments.”

That moment rounds out the reflections, bringing Hunt from a naïve teenager unaware that what he would face was nothing like the images of heroes in movies and comic books to an adult still grappling with the trauma that befell him, his country, and the country in which he spent one hellish year.