By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Most of the origin stories about Valentine’s Day are not true.

There really is no link to any one of the five Valentines who share Feb. 14 as their saint days.

And the connection to the ancient Roman festival of Lupercalia seems tenuous at best. That celebration involved sacrificing dogs and goats, and whipping young women and crops with whips made of the goat’ hides to ensure fertility in the coming year.

The more modern belief that Valentine’s Day is a “Hallmark holiday,” cooked up by the card company to boost sales is also not true – people were exchanging Valentine’s Day greetings for more than a century before the company was founded in 1910.

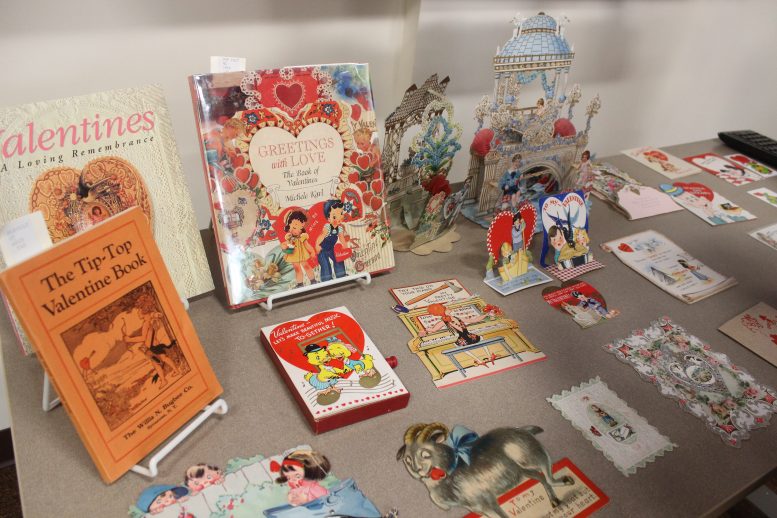

“Most of what we know is probably wrong,” said Steve Ammidown, manuscripts and outreach archivist for the Browne Popular Culture Library at Bowling Green State University. Ammidown visited the Wood County District Public Library to share a selection of vintage Valentine’s Day cards.

Archivist Steve Ammidown discusses vintage Valentines cards with Deb Born (center) and Jean and Chris Geist.

The first reference to St. Valentine’s Day being associated with lovers comes in Geoffrey Chaucer’s 14th century poem “Parlement of Foules (The Parliament of Fowls).”

By the 16th century the tradition of exchanging romantic notes on Valentine’s Day took hold, especially in England and Germany.

Exchanging cards began early in the Victorian Era. True to the times, Ammidown said, “complicated and fragile” was the way to go.

It was a female entrepreneur, Esther Howland, who founded the first Valentine card manufacturer in America in the 1840s. The Worcester, Massachusetts, businesswoman had a staff to create her line of cards, which “were very ornate, very overwrought.”

Ammidown showed a Howland card from the archive’s collection with its intricate patterns and fine, lace-like cut paper. It was meant to display, and its excellent condition indicates it was treasured.

The Valentine card business proved attractive enough that competitors sprang up. The most prominent, George Whitney, eventually purchased Howland’s business. “He became the biggest name in Valentine’s cards,” Ammidown said.

The business flourished at the turn of the 20th century as the post office became more reliable and postcards became more popular, the archivist said.

Though they may have flowery, sentimental sayings on them, sometimes what was written on the back was more pedestrian. The inscription on the front of one declared: “My heart’s a posy blooming for you.” On the back is written: “Your boss said you have to come to work on Monday. He told me this morning. Your mother.”

In the 1920s, students started exchanging cards in school. That gave rise to simpler cards with more age appropriate messages.

Ammidown said that the library’s collection has grown through donations. Many of the cards come from the Armitage family. While the library may be willing to look at collections, Valentine or other, he said, “we’re not really interested taking huge mounds” of them.

The nature of cards changed with the times.

There were vinegar Valentines, he said. They were a reaction to the “sickly sweet sentiments” of traditional cards. One has a woman declaring “I dream of you every night” on the front. Inside it reads: “Wot nightmares!”

In the 1970s, the cards grew racier. Ammidown showed a pair. One depicted a devil declaring: “We’ll have a hot time.” Another pictures a monster: “You bring out the beast in me.” The cards were given by a young child barely old enough to sign them to grandma and grandpa.

In the 1980s, trademarked characters such as the Ninja Turtles and Strawberry Patch Kids made their appearance, and continue to dominate the kid market.

Cards have migrated to the internet where sarcasm reigns. Anti-Valentine cards have also taken hold. These, he said, are “celebrating not being in a relationships.”

One that reads: “The only way I could be lonelier today is if the Internet stopped working.”

The holiday, though, persists, despite such cynicism. After all, kids still make those cardboard mail boxes to collect their share.