By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

For the American doughboys overseas in World War I, mail from back home was a true treasure. To the farm boys who had never been beyond their fields, and the city boys whose borders ended at the edge of their boroughs – mail call was a brief visit to home sweet home.

“Those were the two most important words of the day – mail call,” said Gary Levitt, from the Museum of Postal History located in Delphos, southwest of Bowling Green.

Mail call meant a box of hand knitted socks from mothers, newspaper clippings of hometown festivals or football games from siblings, and letters full of sweet talk from sweethearts back home.

“You didn’t have any other form of communication,” Levitt said recently during one of the monthly “teas” at the Wood County Historical Center. This gathering focused on mail during World War I, since the museum is featuring an extensive look into the war and the Wood County men who served in it.

“To many, letter writing may seem a quaint and charming pastime,” Levitt said. But a century ago, when America entered WWI, it was all families had to keep in contact.

“Writing letters was considered a patriotic duty, along with food rationing and buying war bonds,” he said.

Display on WWI mail service to doughboys, at Wood County Historical Center.

But it certainly wasn’t easy for mail to reach the right destinations, since the doughboys were spread out and many of their troop locations were secret.

“Americans were all over Europe,” Levitt said. “No one wanted to let anyone know where anyone was.”

Plus there were no transatlantic flights, so mail was transported across the ocean by ship. The mail was sorted before it left the U.S., at Chelsea Terminal on the Hudson River, Levitt said. Then it was shipped to Bordeaux in France. If sorted properly, it arrived in France with an approximate location of the recipient.

There were other challenges, Levitt said.

The delays and rough transport was not made for fragile contents. “I’m sure some were supposed to look like cookies when they left the U.S.,” he said.

And many of the troops were illiterate, so the American Red Cross and YMCA sent along staff to help those doughboys who also were desperate to hear from home.

The military has long realized, Levitt said, that having contact with home is nourishment for the soldiers. To help facilitate communication with home, sending letters and postcards to and from the troops was free.

“Mail was synonymous with the morale, and the morale was synonymous with how well they fought,” said Levitt, who said mail call was still vitally important when he served in the U.S. military during the Vietnam War. “It gave us a sense the home fires were still burning.”

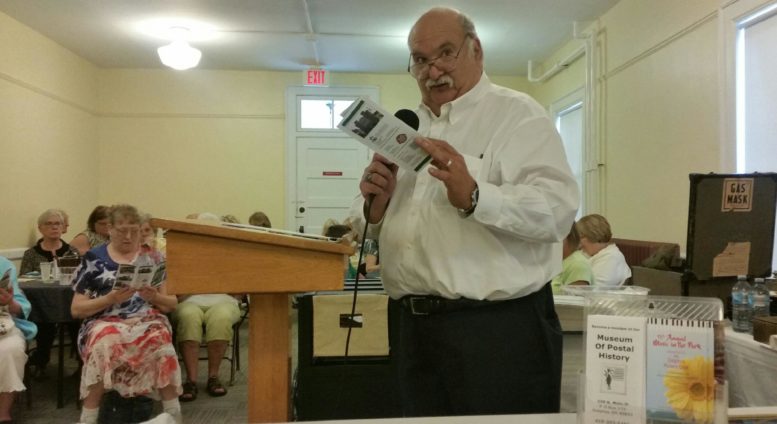

Gary Levitt talks at historical center “tea.”

The letters from the front and from home all went through censors before reaching their destinations. But even a letter missing some words here and there, was treasured.

“Anything to read was better than nothing,”

Except, of course, if it was a dreaded “Dear John” letter. That term was coined later, during WWII, possibly because “John” was the most common male name in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Levitt said.

The letters, especially the preprinted postcards sent home when the soldiers landed safely in Europe, were also intended to comfort families. The cards were printed with updates like, “I’m safe and sound, and feeling mighty fine.”

Levitt read from a few letters sent overseas, including one from a wife telling her husband about tearing up at patriotic songs, and talking of “slackers” who were avoiding military service. He also read words from a soldier on the front lines. “Out here, news of home is like food and drink to us. We live on our memories.”

After about one year into WWI, the U.S. military decided mail service to the troops needed to be handled by the military. So the War Department took over mail delivery. About the same time, air mail started – a service that proved to be quite dangerous, with one pilot death for every 115,000 miles logged.

Wartime mail delivery did lead to advancements in the postal service, with research leading to technology that processed 1,600 pieces of mail an hour – or 10 pieces sorted every second, Levitt said.

The Wood County Historical Center’s WWI exhibit includes a mail room, with samples of letters sent between local families and their doughboys overseas.