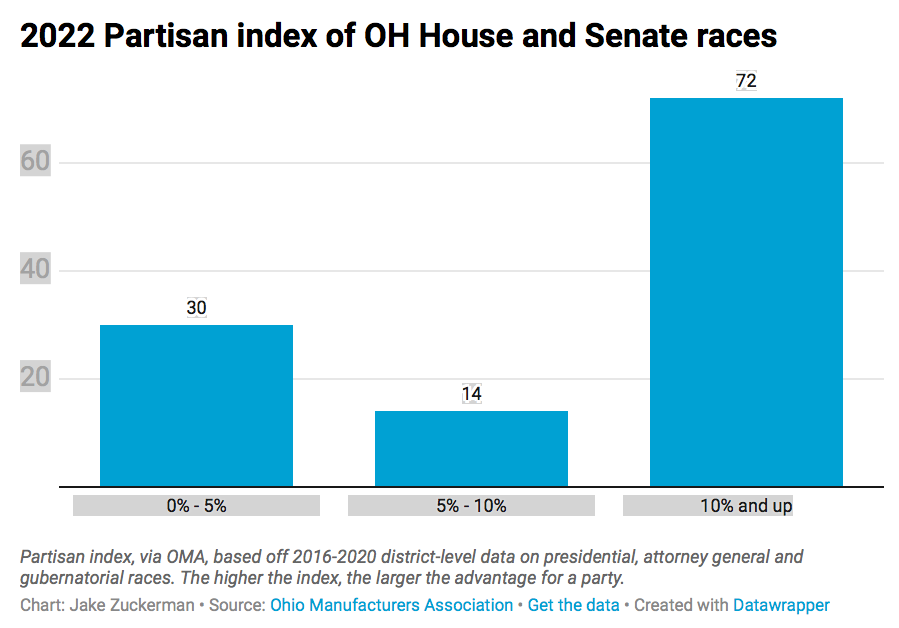

On the first run of Ohio’s new legislative redistricting system, as few as one in four races are likely to produce competitive general elections, a new analysis shows.

All 99 seats in the Ohio House and 17 of 33 Senate seats are up this year. Of those 116 races, just 30 will take place in districts that offer either party less than a five-point advantage, using a partisan index score calculated from the districts’ recent voting patterns.

In effect, this means the composition of most the General Assembly was decided during the August primary — Ohio’s unprecedented second primary election in one year as a result of drawn out redistricting litigation. A near record low of 7.9% of registered voters turned out to vote.

Every election cycle, the Ohio Manufacturers’ Association publishes an election guide with information about the candidates and district makeup in each race. It also includes a political index score derived from Ohio voters’ picks in the district for president, governor, attorney general and U.S. Senate races since 2016. The index is only a crude proxy for voter behavior — a strong candidate could win in a tough district, and vice versa.

However, analyzing the index across 116 races shows just how few are likely to offer any serious contests. For instance:

- 72 legislative races will occur in districts with a 10-point advantage for either party, likely leading to landslides.

- Twenty-seven incumbents are running unopposed (including one race whose Democratic challenger was ruled off the ballot this week). Another five open seats will be unopposed. Those districts are on average significantly more lopsided than those of contested races.

- Of the blowout districts with more than a 20-point partisan advantage, 10 host GOP incumbents, nine host Democratic incumbents, and 13 are open seats.

The new district lines are marginally more competitive than those in effect for the last decade. For comparison, during the 2020 general elections, just 11 House and Senate races were decided by margins of less than five points.

The slate of races is another showing of the lacking nature of Ohio’s purported redistricting reform. In 2015, voters passed a constitutional amendment designed to limit gerrymandering for partisan advantage in General Assembly races.

Along with creating a revamped process for drawing districts (that keeps the power with partisan elected officials), the new constitutional language says the officials drawing districts “shall attempt” not to favor or disfavor either party. Similarly, they “shall attempt” to create districts that “correspond closely to the statewide preferences” of Ohio voters over the last 10 years of elections.

In statewide races over the last 10 years, Ohio broke roughly 54-46 for Republicans. Democrats have argued that they should therefore control about 46% of the seats in the General Assembly, as opposed to their current Senate (8 of 25 seats) or House (35 of 99 seats) minorities.

Conversely, Republicans argued during the redistricting legal fights that because they’ve won about 80% of statewide races, they should therefore control about 80% of the votes. The margin of victory, they said, doesn’t matter. Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose called this logic “asinine” in a text to his chief of staff documented in court filings, but he voted for it regardless.

The Ohio Supreme Court in April ruled the map in effect this cycle unconstitutional — its fourth time overruling a redistricting proposal approved only by Republicans.

In a 4-3 majority opinion, the justices found that Republicans, who controlled the redistricting process, drew maps to favor Republican candidates by disproportionately placing Democrats in “toss up” races while shielding Republicans from the competition. The majority opinion cited an earlier finding criticizing the map’s “remarkably one-sided distribution of toss-up districts [as] evidence of an intentionally biased map.” The court also cited Republicans’ near unilateral control of the map drawing process as evidence of their attempt to favor their own party.

The legislature however has refused to draft new maps, and a federal court eventually ordered the 2022 elections to proceed with the current maps despite the Supreme Court’s objection. District lines for future elections remain to be decided.

The Ohio Capital Journal reached out to the incumbents in some of the most lopsided districts including Democrats Terrence Upchurch (an 89% index for Democrats, per OMA), Juanita Brent (87%), and Dontavius Jarrells (81%), along with Republicans Adam Bird (75% index for Republicans) and Scott Lipps (76%) to ask about the effects of non-competitive races. None of them responded.

Rep. Tavia Galonski, D-Akron, is in a district where about 75% of voters go in for Democrats, leaving her victory extremely likely. It’s nice on a personal level, but she said this isn’t what voters wanted. She castigated Republicans who flouted the intent of Ohio’s redistricting reforms and let a status quo of marginalizing Democratic voting power in Ohio continue.

“The people of Ohio already decided that a noncompetitive race like mine was exactly what they didn’t want,” she said.

“Although I benefit from that, I really question whether Ohioans as a whole benefit from that.”

[RELATED: On Democracy Day, newsrooms draw attention to a crisis in the U.S. system of government]

[RELATED: Discussions underway to propose new redistricting reform to Ohio voters]

[RELATED: Why you should be paying attention to Ohio Supreme Court races]