By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

Unlike people in many other areas of the world, Americans eat less than two-thirds of each animal sautéed, broiled, boiled, deep fried and roasted for meals.

This region of the U.S. relies on a 173-year old company in Wapakoneta to take care of the other third.

Sean Wintzer, president of G.A. Wintzer & Son Co., conceded that the company’s work isn’t pretty.

“We get all the gross stuff,” Wintzer said earlier this week during a meeting hosted by the Center for Innovative Food Technology, located just north of Bowling Green. “It can be a turn-off real quick.”

But the company intercepts tons of food waste prior to it reaching landfills – and turns it into new products from biofuel and livestock feed, to fertilizer and shaving cream.

“We were green long before green was cool,” Wintzer said. “We are critical to sustainability.”

The process used by the company is called “rendering.” It takes animal leftovers – like internal organs, bones, feet, heads, feathers, skin and fat – plus used cooking oil from restaurants, and turns them into products that can be used again.

“Anyone that has a deep fryer has one of our bins,” he said of the brown bins for used old cooking oil.

“Rendering is recycling. I can’t stress that enough,” Wintzer said.

Protein meat and bone meal is sold to Eggland chicken farms. Another protein mix feeds the shrimp sold at Sam’s Club. The fertilizer is sold to Disney for resorts. And the oil can be seen on new bolts purchased at hardware stores.

“We always shied away from sharing our story, because it’s not pretty – but it is essential,” Wintzer said.

He went through the rendering process with his audience, from collection of the waste to creation of new products.

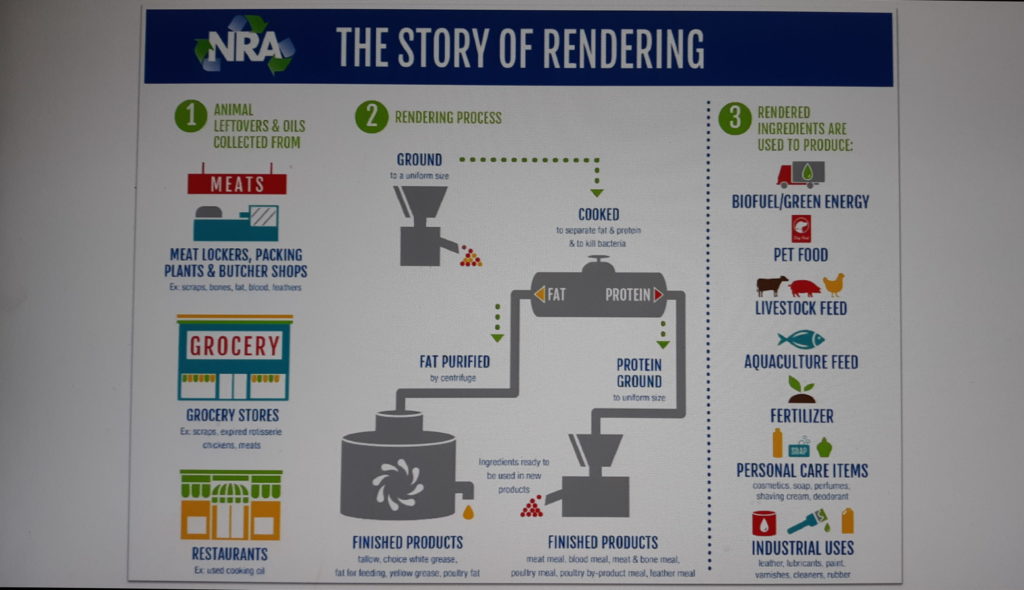

Animal leftovers and oil are collected from:

- Meat lockers, packing plants and butcher shops

- Grocery stores (scraps, expired rotisserie chickens, meats)

- Restaurants (used cooking oil)

The rendering process includes:

- Grinding material to a uniform size

- Cooking it to separate fat and protein, and to kill bacteria

- Fat is purified by centrifuge – finished products are tallow, choice white grease, fat for feeding, yellow grease, poultry fat

- Protein is ground to uniform size – finished products are meat meal, blood meal, meat and bone meal, poultry meal, poultry by-product meal, feather meal

Rendered ingredients are used to produce:

- Biofuel/green energy

- Pet food

- Livestock feed

- Aquaculture feed

- Fertilizer

- Personal care items (cosmetics, soap, perfumes, shaving cream, deodorant)

- Industrial uses (leather, lubricants, paint, varnishes, cleaners, rubber)

The Wapakoneta company has 125 employees, and five cooking lines that work three shifts Monday through Friday, and sometimes on Saturdays. Its fleet of trucks picks up protein food waste and cooking oil in a five-state region.

The company operates its own wastewater treatment to handle the waste.

Wintzers has a contract with every Walmart in Ohio to take meat that has expired in the store. They accept food waste from Pioneer Packing in Bowling Green, and from small “mom and pop” operations that may process one or two deer a year.

The company picks up used cooking oil from more than 8,000 restaurants.

The business began in 1848, and has been carried on by six generations of the Wintzer family. Initially, the founders purchased hides and skins from the Shawnee tribe near Wapakoneta, the current company president said.

They tanned the hides using oak bark and chicken manure, then would spread the solution on streets to keep the dust down.

In the 1920s, the company evolved when it was decided the business should branch out by picking up the other unused parts of animals – not just the hides.

The company is big on education, according to Wintzer. One of the earlier generations of the family went to OSU, but dropped out because he was bored. His father would not allow him to join the business until he completed his education – so the son went off to Chicago, where he became foreman of a large animal rendering plant. When his father realized all his son had learned, he welcomed him back to Wintzer & Son.

The company survived COVID better than originally predicted, Wintzer said. Many restaurants closed initially, and once they opened, many people were too cautious to eat out. So the company expected its used cooking oil collections would drop by 60%.

“It was the complete opposite of what we thought was going to happen,” he said. “It picked right back up. There was a push by communities to order takeout to keep people in business.”

And with federal funding helping to get people through the pandemic, Wintzer noticed that people were buying protein – steak and chicken – as is customary when the economy is good.

The biggest challenge facing his company is government “messing with private sector business,” he said. “Regulations are good to an extent.”

Wintzer was critical of COVID regulations shutting down “unessential” businesses.

“We were lucky because people have to eat,” he said. “All business is essential.”

The rendering industry is also facing a challenge from the composting industry. According to Wintzer, rendering is more sustainable than composting.

“We need to make sure people in Washington understand our story,” he said.