By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

When he as a kid all Danny Trejo wanted from the adults in his life was time.

But they were too busy, especially his father. Whenever his father was not out on a construction job, he was busy with projects around the house.

The one adult who did have time was his father’s youngest brother Gilbert. He, unlike the other males in the family, was always smiling because he was always high on marijuana. He was more than willing to take young Danny under his wing, giving him his first joint when he was 8 years old.

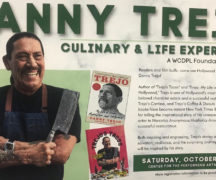

Now an actor, author, restauranteur, and inspirational speaker Danny Trejo shared his life story Saturday night in the Bowling Green Performing Arts Center as part of the Wood County District Public Library’s Foundation Series.

It was a tough way to grow up, but Trejo, 78, wasn’t laying blame. Instead he insisted: “My life is blessed.”

He admitted despite his own anti-drug advocacy two of his three children ended up with drug problems. Unlike him, though, when they needed help he was there to guide them into treatment.

When he was young his uncle guided him into a life of drugs and armed robberies.

By 9 Trejo was skilled at rolling a joint for sale, and sneaking a few into his pockets for his personal use.

. He was braver facing bigger guys protecting their turf after he’d consumed some wine stolen from a neighborhood store.

He was booted out of high school five times.

Robberies ended him up in juvenile detention, and eventually time in every one of California’s penitentiaries. He noted there are more now – prisons are a business, and they count on a high percent of inmates coming back after their release. Three-strikes laws are part of their business model.

In 1969, Trejo didn’t think he’d ever get out of prison, he went before the parole board. They told him they were sick of having him around, and paroled him with the expectation that when he returned he’d be facing a life sentence..

But Trejo had kicked drugs. He was living with his mother and trying to find something to do. He saw the neighbor struggling with hauling her trash can out to the curb. He approached her to help. She just wanted him not to rob her.

“She didn’t take her eyes off me,” Trejo said.

That suspicion was well earned. He’d stolen every lawn mower on the block.

Still he continued to help her, and after a few weeks she gave him a blue suede double breast blazer that had belonged to her late husband. He realized helping people was what he needed to do.

“Every good thing that happened to me was a direct result of helping somebody else,” he said.

He helped another woman whose lawn, thanks to chemical treatments, had been a show piece. The kind of lawn that made everyone else’s place look bad, he said. When he came home from prison, it was choking with weeds, the flowers were gone. His mother told him that one of the woman’s sons had died in Vietnam and another because of urban violence. Then her husband committed suicide.

So Trejo and a neighborhood buddy worked on the lawn, reviving it – without the chemicals, Trejo noted.

They did other lawns for pay. They’d take the lawnmower from the first job and then use it for the rest because they didn’t have their own. Then they were approached by White guy. He addressed them as “Poncho” and Pablo,” even though Trejo’s partner was not Mexican. In his mind, Trejo was adding up what they’d charge him extra for the disrespect. The customer brought them to his garage. It was fully stocked with lawn care implements. They could have all of it, if they did his lawn. He loved taking care of his lawn, but he had back problems and couldn’t any more.

Now they were in business. Through Trejo’s father they started getting jobs at a new housing development. Eventually they had an eight-man crew and three trucks. Both Trejo and his partner decided they wanted to do something else, so they sold the business.

Trejo wanted to be a drug and alcohol abuse counselor.

He was working as a counselor when one night he got a call. One of his clients had a job, and there was a lot of cocaine around. He needed Trejo’s support to stay straight. Trejo thought the guy worked at a warehouse.

When he got to the job site he realized that it was a movie set.

The film’s plot involved escaped convicts. The director wanted to know if Trejo could play a convict. That just involved him standing around, Trejo said.

Then one of the other extras recognized him from San Quentin where Trejo was a championship fighter.

Trejo ended up with a bigger role on screen, and as a boxing trainer for star Eric Roberts.

“Runaway Train” put Trejo’s acting career on track.

Now, he said, “I’ve heard ‘that’s the guy from ‘Spy Kids’’ in 40 languages.”

He’s written two books “Trejo’s Tacos: Recipes and Stories from L.A.” and “Trejo: My Life of Crime, Redemption, and Hollywood,” co-written Donal Logue.

He’s also been involved in numerous food and restaurant businesses. He told the Bowling Green crowd that he’s planning a combination performance venue and restaurant for Detroit. All that comes, Trejo reiterated, because he helped someone else.

Now, he said, “the people I run with are clean and sober. … Alcohol and drugs are stronger than you. … Life is great without them.”