By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

When Fred Tomaselli was a young painter, he felt the weight of history. What more could he contribute to the grand tradition of painting? Instead he looked around and saw new media emerging, installations and video art.

So he did a seascape, not with oils, but with foam cups tethered to wood and set in motion by a breeze from a fan. Tomaselli, 59, said he turned the flotsam and jetsam that normally float on the water into the water itself. He turned something that holds liquid into the liquid itself. Tomaselli plays tricks with perception. He brings together conceptual art with representational art. He pleases the eye and tweaks the brain.

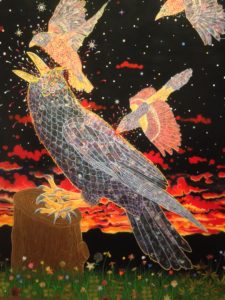

As he related in his Master Series lecture Thursday at the Toledo Museum of Art, his artistic journey led to a return to painting and intricate representations of birds. Those images, part painting, part collage, are made up of smaller images. Scott Boberg, the museum’s manager of programs and audience engagement, noted in his introduction, in one Tomaselli painting the viewer discovers “a bird beak that’s literally dozens of bird beaks.”

As he related in his Master Series lecture Thursday at the Toledo Museum of Art, his artistic journey led to a return to painting and intricate representations of birds. Those images, part painting, part collage, are made up of smaller images. Scott Boberg, the museum’s manager of programs and audience engagement, noted in his introduction, in one Tomaselli painting the viewer discovers “a bird beak that’s literally dozens of bird beaks.”

Those paintings are on view in the museum in “Keep Looking: Fred Tomaselli’s Birds,” continuing through Aug. 7. The exhibit and the talk coincide with what’s considered the biggest week in birding as flocks migrate, stopping on the shores of Lake Erie before continuing their journey north.

Tomaselli apologized at first, explaining the talk would not be all about birds. Rather he explained how his imagination took flight starting as a child in Orange County, living near Disneyland. What he saw in the sky was Tinkerbell. He was influenced by “that friction between reality and the construction of reality.”

Tomaselli apologized at first, explaining the talk would not be all about birds. Rather he explained how his imagination took flight starting as a child in Orange County, living near Disneyland. What he saw in the sky was Tinkerbell. He was influenced by “that friction between reality and the construction of reality.”

Tomaselli experienced the battles between the various schools of art. “I liked it all,” he said. “It all seemed to have some validity to me. … I was a kid. I didn’t have any skin in the game.”

The son of an Italian immigrant, Tomaselli left California in the 1980s to resettle in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn. He was interested in capturing “other realities.”

“I’d taken a lot of psychedelic drugs,” he said.

He adopted an unlikely medium – over the counter drugs. He did portraits of people by creating constellations based on their astrological signs using pills for the stars. “I was thinking that looking up to the heavens was man’s earliest way of turning his back on the world.”

He created these on wood, encasing magazine clippings and drawings under a thick layer of resin. The work made use of his carpentry skills. In his California youth, he made surfboards. In New York he was “a handyman for a slum lord.”

But throughout this time, he continued to paint outdoors. He thought of it as a pastime, something he enjoyed doing. “There’s nothing I can remember in more detail than what I’ve drawn from life.”

The pills gave way to cannabis leaves. “It opened me up to the shape of nature,” he said. “This became a bigger part of my work.”

When bugs interfered with his work outside, he decided to lure them onto the surface of his paintings, encasing them, along with drawings of insects and magazine clippings, with resin.

He doesn’t just view a scene’s surface. “When I saw landscape, I saw it through a scrim of different information,” he said. For him it evokes land taken from natives or the watershed.

“New Jerusalem” seems a folk scene of a tranquil village, yet has an unsettling theme. The structures are the Charlie Manson house, the Unabomber’s cabin, an Aryan Nation compound. It’s a reminder that the country’s history includes slavery and the genocide of indigenous people.

There is politics in his work, no more so than in his series of pieces based on the front pages of the New York Times. He grew “apoplectic” during the build up to the second Iraq War. He painted and drew images on top of those in the newspaper. “The calamity of the world began to enter into my work in a bigger way,” he said.

“You don’t have to believe anything I’m saying,” Tomaselli said. “You can just like it visually, formally.”

He did finally explain how he became fascinated with birds. “Birds always seemed remote to me,” he said. “They always seemed a little too far out of my perception to get a grip on me.”

Then his brother invited him to go on a hiking and birding trip in the area just outside the Mojave Desert. With his brother’ guidance and a pair of binoculars – “enhanced optics,” he discovered birds in all their wonder.

Noting that he’d be out in the McGee Marsh early the next morning to observe the birds, Tomaselli said that birdwatching is “this little thing that keeps me from making art in my studio.”

Then he told the audience, they really needed to get out and see his art for themselves. The slides he was showing couldn’t capture the works’ textures. And many in the audience did, crowding in Gallery 6, surrounded by birds, pointing to each detail as if they’d spotted a rare species on the fly.