By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

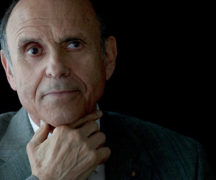

Tenor saxophonist Joel Frahm is happy to be back on the road.

The pandemic disrupted his life, forcing him to relocate from New York City when work dried up, to his parents’ home in Connecticut, and eventually settling in Nashville.

Now things are opening up, and with a new recording out this summer, he’s bringing his trio with Dan Loomis on bass and Ernesto Cervini on drums to Bowling Green for a show at Arlyn’s Good Beer, 520 Hankey Ave., Bowling Green, Tuesday, Oct. 12, and then will present a clinic at Bowling Green State University on Wednesday.

“The chance to play with other people again is a pretty major boon for all of us,” Frahm said in a recent telephone interview. “I know I missed it terribly. I missed playing with my peers. So the first few gigs back I get to play, it really just feels joyful. It feels amazing. Things we took for granted in the past feel very new.”

The saxophone trio, without a chording instrument – no piano, no guitar – is a favorite format for Frahm, but “The Bright Side,” which came out in June, is the first album under his leadership with that instrumentation. The album also features Loomis and Cervini.

The saxophone trio has a storied past with such notables as Lee Konitz, Joe Henderson, and Sonny Rollins recording classic albums. When Frahm was 17 a teacher asked him to transcribe one of Rollins’ “A Night at the Village Vanguard” albums.

“It’s challenging and appealing at the same time,” Frahm said of the “chordless” trio. “It can be very stark. It’s tough to make it colorful because you have no harmonic instrument. But the cool part of it is all that space allows me to function … not just as a tenor saxophone but also as an accompanying instrument and play more pianistically, actually spelling chords in the air like piano player would. That extra space allows me a lot of room to try different things and see what happens. It’s a little wilder and woolier, but maybe that’s what’s cool about it, too.”

This trio came together while Cervini, Loomis and Frahm were playing in Toronto with Cervini’s sextet Turboprop. They did a master class as a trio, and afterward the drummer and bassist approached Frahm wondering if they lined up gigs as a trio would he go on the road with them. Frahm was game.

Frahm, 51, started his musical training playing piano at 5, and then saxophone at 13. But it was not until his family moved from Wisconsin to Connecticut that he connected with the music that would become his love.

There he met some older players who introduced him to jazz. “I became pretty obsessive learning to play that language.” Before he graduated from high school he knew “that this was the path I was going to take.”

He went first to Rutgers and then to the Manhattan School of Music.

His career has been “a roller coast ride for sure.”

Early on Frahm “cobbled together” a living playing in a blues band, at weddings, giving lessons and the occasional jazz gig. Then in the late 1990s, he was selected to participate in jazz singing legend Betty Carter’s Jazz Ahead program, a preprofessional residency at the Kennedy Center. His class included future stars Greg Tardy and Eric Harland.

“It was an amazing group,” he said. That “stamp of approval … gave my confidence a boost.”

He was able to move on to a career that’s spilt half and half between performing and teaching. He does not, however, have a college job, rather he teaches master classes. In the early 2000s, he worked with vocalist Jane Monheit, which brought him to BGSU for a concert. He visited later to perform and teach at the behest of David Bixler, director of Jazz Studies at BGSU.

Making a living as a musician certainly hasn’t gotten any easier.

There are a number of outlets. A woodwind player can learn to play a variety of instruments, and work in a Broadway show orchestra. Or a musician can get an education degree and teach.

“It’s not an easy profession,” Frahm said. “ It’s not something to enter into lightly.”

While it may seem simplistic, there’s still truth in the catchphrase: “Take care of the music and the music will take care of you.”

Musicians need to focus on mastering the fundamentals. “A lot of times musicians get so caught up in promoting themselves before they really have something to promote,” he said.

While the business is tough, as Frahm can attest, he said: “I’m still an optimist. I still think there are ways of doing it. I’ve done it. I’ve seen younger peers of mine doing great, who have stayed the course and worked really, really hard. Basically the opportunities will come with persistence. There are people out here who work really hard. They’ll make something happen.”