By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Peggy Giordano’s life in criminology started in a black VW bug.

A Spanish major at the University of Missouri, she worked in the Sociology Department office. She found the work there more interesting than what she was studying.

When a researcher enlisted students to ride along with police in their communities, she volunteered. She was the only woman.

While the males were able to ride in the cruisers, it was deemed unseemly to have a young woman riding in the car with an officer. So with the tacit approval of the police, Giordano tailed them in her black VW bug.

“Over time we’d start to talk to each other over the trays at Shake and Bake,” Giordano said. “They got to know me,” They made sure she knew where they were headed.

“I really got into it. I’d sit out in grass and watch them do traffic stops .”

Giordano found it fascinating how the police would be lenient with some drivers while they gave others a hard time.

She went on to get her doctorate in sociology at the University of Minnesota and in 1974 joined the faculty of the Bowling Green State University. “It’s stunning to say that” Giordano said. “It’s been a good place to do research. It really has.”

In October, the Swedish Ministry of Justice announced that Giordano was a co-recipient of the Stockholm Prize in Criminology, the top honor in the field.

Giordano didn’t take the call at first, suspecting a scam. Then she looked at the number, and made the connection. She thought maybe they were letting her know that she’d been nominated. She was shocked when she found out she had won.

“They have jurors from different countries. It truly is international.” She will travel to Sweden in June to accept the prize.

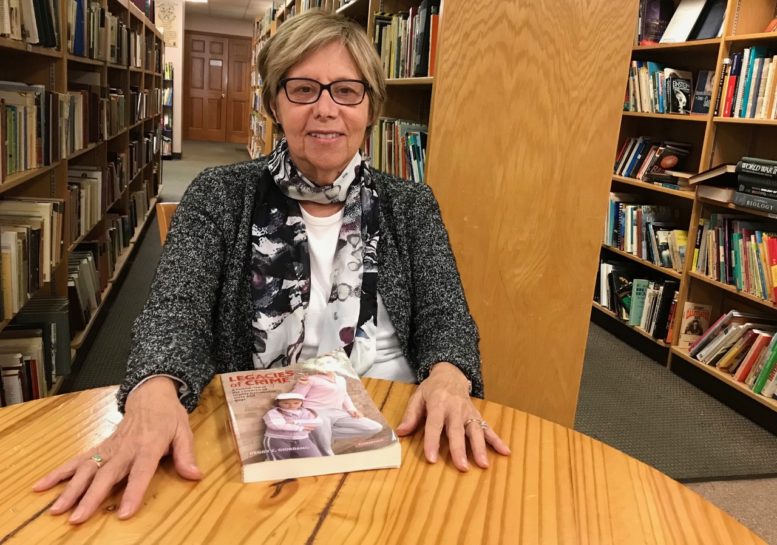

And while other recipients have a number of books to their credit, Giordano has one book, “The Legacies of Crime: A Follow Up of the Children of Highly Delinquent Girls and Boys” and a seminal scholarly paper on gender, crime, and desistance Gender, Crime, and Desistance: Toward a Theory of Cognitive Transformation. Desistance is whether someone can leave the criminal sphere.

The honor was for her body of work that has involved tracking people from when they are teens until they have teenage children themselves.

Most research, she said, focuses on why people get involved in crime, or they look at particular programs to help them turn their lives around.

Her focus is more on how some people, as they mature, abandon crime, while others become “hardened career criminals,” she said. But even some of the latter may quit. What factors influence those choices?

These are the questions that fascinated her.

The first project, conducted with her BGSU colleague Stephen Cernkovich, looked at girls and women in crime. They started with a sample of girls from Toledo and a group of males for comparison. But “maybe these people aren’t delinquent enough,” they wondered. So they interviewed all 127 inmates incarcerated in the state institution for girls, as well as an equal number of incarcerated men.

In 1995, they decided to see if they could locate the original subjects and to see how they were doing. They located 85 percent of them.

Throughout this research she was aided by the work of Claudia Vercellotti who conducted most of the in-depth interviews. “She’s been really important to the study,” Giordano said. “She has the extraordinary ability to give people the respect that they deserve even if they may be marginalized. People will tell her just about anything. You have to be very neutral .., otherwise they clam up.”

Vercellotti’s 90-minute interviews which produce 100-page long transcripts are “really unique in the field.”

These life narratives reveal how change happens for the subjects.

Giordano took her time absorbing and studying the research. The scholarly article was published in 2003, and was key to the Stockholm Prize committee. It is, she said, her most cited work.

“I’m very interested in social process. How they get along with their peers. What’s going on in the family. Is there a family history of crime?”

From this evolved the theory of cognitive transformation. People must change how they think about their lives, but there also must be supporting social structures.

“It’s more complicated than just getting yourself a wife or getting yourself some employment because if you’re not really motivated to change then that employment experience isn’t necessarily going to take hold and make you change your identity.”

Some people are more receptive to different “hooks for change.” They may say it’s because of their children. Or they may turn to religion. They may join Alcoholics Anonymous. They may get married.

But it takes more than these individual actions to turn their lives around, Giordano said.

She looked at the extent to which social experiences could stabilize and support those initial motivations to change. “You’re not making those decisions by yourself,” she said. “Through the whole paper I tried to emphasize that other side of change. Your networks are important in helping you sustain that over the long haul. Lots of people can say sincerely they want to change or wanted to change, but then they may live in an apartment where there was a crack dealer living in the apartment below. You have to look at their social circumstances and how that can be sustained or derailed.”

These insights that can be derived from long-term studies.

At the presentation held at BGSU announcing the prize, one of the speakers talked at length about a case that appeared in the 2003 paper. It involved a woman who said that her life was dedicated to her son now. She was done with crime. Her son talked about how he’d flushed his mother’s drugs down the toilet. He pledged he wouldn’t turn out like her.

A success story.

Giordano felt she needed to provide an update. When researchers contacted her later the woman was back in prison, and her son is in prison as well. “It’s just devastating.”

More women than men cite their children as driving their need to change, and yet a majority of women in prison have children, so that is clearly not enough.

So what’s needed is stable housing. “Housing is so immediate,” Giordano said.

In one case, a father and son were in prison together for a series of burglaries of abandoned homes, a scheme his father had hatched. When the son was released, he ended up having to live with his father. That’s all that was available.

“What we can do as a society is to help them and support them with housing with companions that are going to be more prosocial,” Giordano said.

A lot of young people talk about moving from school district to school district. “Because they’re having to move so much that just leads into school failure and that leads into crime,” she said.

There’s also a need for high quality drug programs that are accessible. Change, she said, requires a combination of motivation and availability.

Giordano has also worked with fellow sociologists Wendy Manning and Monica Longmore on the Toledo Adolescent Relationship Study (TARS) that has been following more than 1,300 Toledo-area teens for two decades, interviewing them every couple years or so.

Giordano retired as a Distinguished Professor at BGSU in 2009, then returned the next fall to the faculty to focus exclusively on her research.

“I still enjoy it,” she said. “I’m just not sure how long this will continue, but I guess just as long as I keep being energized by it.”

And what energizes her is not the recognition. She concedes she’s not interested in media attention. She doesn’t recall her appearance on “Good Morning America” fondly. She was like deer caught in the headlights.

But what does excite Giordano is being on a Zoom call for an update on the TARS research and hearing of a new findings from graduate students. “It’s always been that way,” she said. “It’s just the work itself.”