By JULIE CARLE

BG Independent News

Capturing the essence of Sandra Faulkner’s “Poetic Portraits of Older Women in the Great Black Swamp” has challenges in a news article.

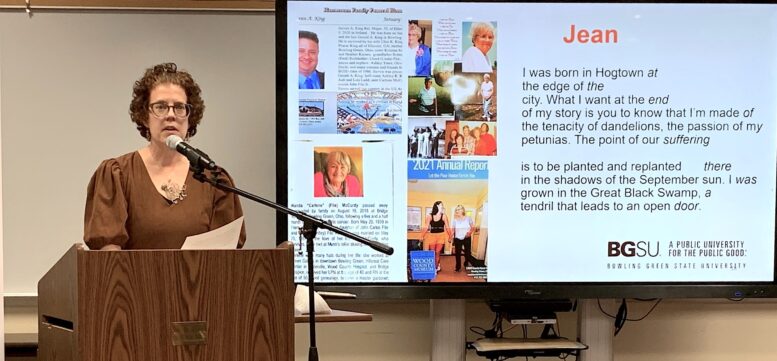

The rhythm of the phrases, the turn of a word, or the visual cues added to the written poetry don’t seem to hold the same aesthetic here as listening to Faulkner carefully and respectfully present her academic and artistic project last week. The Bowling Green State University professor of communication shared poetic interpretations of eight local women who have helped shape the Great Black Swamp and the greater Bowling Green community.

Though their similarities as members of an “older women” demographic, with ages between 64 and 80, their life stories revealed their differences. Two of the women moved to the area after retiring; one grew up here, left, then moved back; three moved here to attend BGSU and never left; two were born here and stayed.

“The stories the women told me were filled with pain and joy, trauma and triumph, the expected and the unexpected,” said Faulkner, who is also a Faculty Fellow for the BGSU Institute for the Study of Culture and Society.

They shared feelings about getting older, being old, and the importance of relationships and family, regardless of whether they were single, widowed, divorced or had long marriages.

They also talked about the sense of community in Bowling Green and Wood County and the friends that have helped sustain them.

Women of Poetic Portraiture

- At 80, Jean was the oldest, but the only participant who shared her life story settled in at Faulkner’s dining room table. Amidst the traumas of her life, she detailed how flowers were the blossoms to memories of her mother and sister.

- Lisa at 64 was the youngest and the only African American woman interviewed. The spirited said relationships, travel and being a lifelong learner are her core values. As a single woman and only child of a mother and grandmother who were each an only child, she saw the project as a way to ensure her legacy.

- Barb, a 76-year-old who doesn’t like being old, is sad that her body can’t keep up with her mind. Though it slows her down it doesn’t stop her. She walks her dog and is involved in a hobby of living history, stitching 18th-century clothes by hand.

- Laura grew up in Oklahoma and moved to Bowling Green to be close to one of her sons after her husband was diagnosed with ALS. The 76-year-old had been labeled an underachiever as a child yet went on to become a music teacher, only to find out in her 40s that she had brain damage when she was born feet first.

- Another 76-year-old, Doris has embodied the spirit of a public servant her entire life. She was first a county extension agent for her career, retired and now serves as a county commissioner—the second female commissioner in the county.

- Pam, who never left town after she came to BGSU and met her the man she would marry, is rooted in authenticity. After dealing with “invited and uninvited challenges” of breast cancer and the death of her daughter, the 67-year-old has learned to be herself, be open and honest with others and immerse herself in the beauty of nature and artwork.

- At 71, Melissa is one of the women who grew up in Bowling Green and graduated from BGHS and the university with a degree in speech and theater. She left BG and earned the title of trailblazer for deaf and intellectually challenged children, and returned to BG after retirement, only to continue her involvement in theater.

- Deb, a 70-year-old woman, is also involved in theater and the community. She described her trajectory as one of reinvention. After coming to Bowling Green for college, she pursued a master’s degree in popular culture, a career in marketing and communications, and a restauranteur before moving on to community service-based activities.

A process perfect for sharing life stories

The goal of the project was to co-construct and portray the lives of older women in multiple mediums and to provide public access to the completed works, Faulkner explained.

The art-based research process eventually creates a person’s embodied experiences of their life stories in poetic form. The process starts with a recorded interview, which is turned into a poetic transcription, or “poetry masquerading as a transcript and a transcript masquerading as a poem,” she said.

When creating the poetic transcription from the interview transcripts, special attention is paid to line breaks and how the words look on the page.

From the poetic transcription comes the poetic portrait— “a poem or series that captures the spirit, contours and specific nuances of the interviewee’s life story and experience,” Faulkner said. She often uses images, collages or other visuals that articulate authentic lived experiences.

As part of her project, it was important to tie the science of research to the art of poetry. “Poetry is a way to bring alive some of that work,” using empathy and reflection in the process.

The invisible demographic

Faulkner established her research to allow older women to tell the stories they wanted to share in their own words. She believed that focusing on older women would give voice to a group that is marginalized and understudied.

“Older women report feeling ignored and silenced,” experiencing more invisibility compared to older men and younger women, she said. “Old woman invisibility syndrome is being seen and devalued or not seen at all.”

They experience intersectional discrimination at the intersection of racism, sexism, ageism and ableism, she said.

Through her work, Faulkner hopes to break down stereotypes and challenge dominant ideas about women who are aging and initiate intergenerational conversations.

“Sharing these stories benefits all of us,” she said.

Local life stories in poetry

Each of Faulkner’s beautifully composed poems conveys how the women’s relationships and life circumstances influenced their lives. However, she admitted the process was nerve-wracking at times. “How do you honor the story? How do I take words and do honor to these stories?”

Their stories also demonstrate how their lifelong experiences have helped shape their sense of self. Excerpts from a few of the portraits follow:

For Laura’s poem, references to her undiagnosed disability as a child and her successful musical career are included in the prose poetry Faulkner utilized. Prose poetry looks like prose and reads like poetry but relies on rhythm, repetition and fragmentation of music.

Because my brain couldn’t copy the rote beats of the everyday (rest) and short-circuited thoughts got stuck in one hemisphere (rest) teachers labeled me a big L for underachiever … Because no one gets up in the morning and decides to screw up (rest) music connected the parts that were missing (rest) music pulled together the cacophonous notes

Lisa’s poem used a skinny form that is good for showing emotion and compression of data, Faulker said. The poem, “The Rhythm of Relationships,” offers the essence of Lisa’s work as an author and explains why she wrote books.

Life is learning to write the

book without a title;

Relationships

have

a

heartbeat.

Relationships

are

the

rhythm.

Relationship

a book without a title, life is

learning to write.

A Mobius strip, created by attaching ends of paper with a half twist, was the form Faulkner chose to present the life story of Barb. There is no beginning or end, which made sense for her story that included aging issues and triumphs of personality and community, Faulkner said.

I am living history at 76

My mind outpaces my body.

Metal pieces hold the hinges together

Those Golden Years? I don’t know, they must be coming later, I guess. … I sew 18th-century clothes for fun—aprons, bedjackets, petticoats—always by hand. No machine, with perused material like cotton quilts My body tells me I’m done with things like sexual orientation and relationships that tear me into strips of fabric that my needle can’t fix.

Jean experienced trauma in her life, but she wanted her story to be about flowers and how her mother and sister were her life support, Faulker explained. The details needed to be told in explicit language, “with me as a narrator, trying to relay trauma before I could get to the flowers. The trauma shows why flowers are so important and rooted in survival and resilience.”

But first, witness 80 years of living, working and parenting in a small rural town with roadside ditches built to mask the swamp that this place once was. As if the past could be drained away. …

I was born in Hogtown at

the edge of the

city. What I want at the end

of my story is you to know that I’m made of

the tenacity of dandelions, the passion of my

petunias. The point of our suffering

is to be planted and replanted there

in the shadows of the September sun. I was

grown in the Great Black Swamp, a

tendril that leads to an open door

Life legacies to be archived

The research work by Faulkner and the stories of these eight women, and potentially many more, will be archived with the help of the BGSU Center for Archival Collections. The anticipated unveiling of the Poetic Portraits archival project is appropriately planned for Women’s History Month in March 2024.