By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

Besides agreeing that kids need good schools, there seemed to be little common ground plowed Wednesday evening when a local farmer met with Bowling Green City School officials, teachers, parents and community leaders.

After helping to send out 5,000 mailers to district voters, urging them to vote against the school levy, Richard Chamberlain was asked to attend one of the superintendent’s coffee chats Wednesday evening. Chamberlain came armed with a stack of property tax bills.

Chamberlain said the 6-mill school levy is putting the bulk of the burden on farmers. School officials said they are trying to give students the schools they need to succeed – and a property tax is their only option.

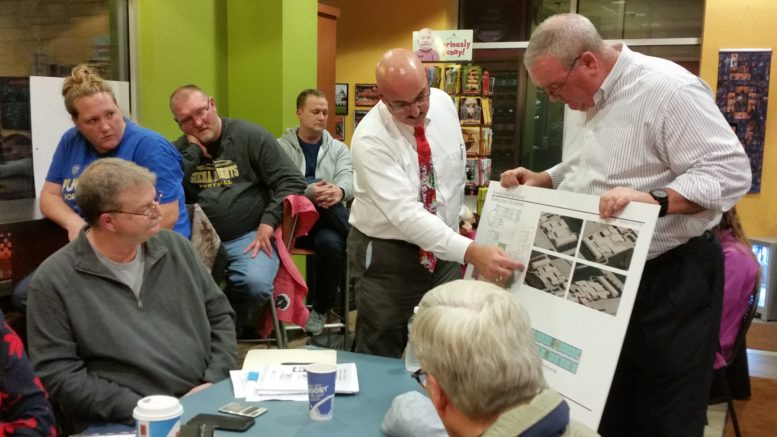

Superintendent Francis Scruci explained the school building project to Chamberlain, showing him the charts that he carries everywhere. Plans call for the consolidation of the three elementaries on property north of the middle school, and for renovations and an addition to the high school.

“I appreciate it,” Chamberlain said. But it’s the way the project is being funded that doesn’t sit well with the farmer.

“You would be more than willing to push the burden for this great project onto the few,” he said. After the meeting, Chamberlain said all he wanted was school officials to admit they were unfairly putting the millage on the backs of the farming community.

But Scruci and High School Principal Jeff Dever said the district needs new schools, and the state legislature has left them with no other options for funding.

“We want to improve the education for the children, and we’re doing it under Ohio law,” Dever said. “We’re just trying to improve the education of our kids.”

“We owe it to the community to support our children,” a parent said.

Scruci said he has not hidden the fact that the 6-mill levy for a $72 million bond issue is a lot of money. “We told people this bond is expensive,” he said. “But we know the condition of our buildings.”

The superintendent has spoken at nearly 100 public settings about the levy and building plans, including three meetings with members of the agricultural community.

“With all due respect, we had conversations for 15 months before we made a decision,” Scruci said. And during that time, he heard nothing from the Chamberlains.

For the owner of a $100,000 home, the levy will cost an additional $210 a year in property taxes. That’s a pittance compared to the amount farmers will be dishing out, Chamberlain said. His family owns approximately 2,200 acres. Most is farmland, but it also includes mobile home parks in Rudolph and Jerry City.

Chamberlain said his family currently pays about $60 an acre in property taxes. If the school levy passes, they will be paying another $6.53 an acre. So for 1,000 acres, he is estimating the bill will be an additional $6,530 a year.

Chamberlain said his family has farmed their land for generations. “I have roots so deep here.”

“All of that ground will end up with the last generation if we can make it,” he said after the meeting. “It’s a fight for us to survive.”

But others at the coffee chat viewed it a little differently. Some had trouble sympathizing with a person owning thousands of acres.

Since 2008, property taxes have increased dramatically for farmers because agriculture has experienced the largest and longest period of prosperity in American history. Farm incomes and farmland values are used to calculate real estate taxes and both were at record levels.

“This is based on property assessed values,” school board member Ginny Stewart said. “All we’re asking is for you to pay your fair share.”

“The vast number of people would be glad to own 1,000 acres,” Scott Stewart added.

Chamberlain said farming is a tough profession. “We work very, very hard.”

“We all work very hard,” Ginny Stewart responded.

During the meeting, a parent used her smart phone to check on the property taxes, and discovered that she pays more on her seven acres than Chamberlain does for one of his 50-acre parcels. She suggested that Chamberlain exercises his right to vote against the school levy, but not to present inaccurate information on the issue.

Chamberlain asked why the district chose to use a property tax, rather than income tax for the building project. He read aloud from a publication stating that schools could use income taxes for such projects.

But Bowling Green’s board of education has been advised by its attorney that it can only use an income tax if it is using state funds – and then only for the co-funded portion of the project. Scruci explained that because the state considers Bowling Green to be an affluent district with property valuation of $651 million, the state would only help with 10 to 13 percent of the building costs. And with that help comes a lot of strings that result in less local control of the project and the possibility of an even greater end cost.

“I would love the schools to have everything they want,” Chamberlain said. “Far be it for a farmer to tell you what you need.” But why put an unfair portion of the burden on local farmers, he asked.

“You’re asking the wrong person,” Scruci said, since it would require an act by the state legislature to change how schools are funded in Ohio.

Dever pointed out that parents looking to locate in Bowling Green tour the schools, then end up moving to areas like Perrysburg, Anthony Wayne or Sylvania.

“I never hear from them again,” Dever said.

Every other school district in Wood County has new buildings, most of them with consolidation.

It’s time for Bowling Green to catch up, said Nathan Eberly. “I’m sick of hearing my friends say they don’t want to move to Bowling Green because of the schools,” he said.