By JULIE CARLE

BG Independent News

Just as the Covid-19 pandemic was moving into high gear in the second quarter of 2020, Ohio hit an all-time peak in the number of opioid overdose deaths. At 11.3 deaths per 100,000 people, the spike was after more than two years of a slight downward trend from the previous high of 10.87 deaths per 100,000 in 2017.

Now, an Ohio team of experts armed with data and scientific knowledge is targeting plans to combat the opioid epidemic that kills over 4,000 Ohioans each year. According to Dr. Jon E. Sprague, Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation eminent scholar and director of science and research for the Ohio Attorney General’s Office, the Scientific Committee on Opioid Prevention & Education (SCOPE) is implementing a four-pronged attack on opioid use deaths.

Sprague was the featured speaker for Bowling Green State University’s first Science Cafe livestream event for the 2022-23 academic year on Tuesday (9/20). In addition to outlining the state and national trends in opioid overdoses, he shared “the efforts we’ve made using science to develop innovative methods to combat this issue at the state level.”

Professional education, opioid storage and disposal, behavioral economics and pharmacogenetics are the initial tools the committee is proposing to reduce the opioid overdose death rates in Ohio.

The purpose of the science cafe format is to encourage formal and informal conversations between scientists and the public.

The most recent national statistics are for 2021 when the Centers for Disease Control estimated there were more than 107,000 drug overdose deaths in the U.S., or approximately 170 fatalities every day. “Most of the deaths were people between 18 and 45 years of age, and the primary driver was illicit forms of fentanyl,” Sprague said.

“When we talk about the opioid epidemic, it is described in three waves of the rise in opioid overdose deaths per a population of 100,000,” said Sprague, who was the former director for the Center for the Future of Forensic Sciences at BGSU.

Wave 1 is a rise in prescription opioid overdose deaths that started in 1999. Wave 2 is a rise in heroin overdose deaths that started in 2010 and leveled out in about 2017. Wave 3 is a rise in synthetic opioid overdose deaths that started in 2013.

The state trends were similar to what was going on at the national level. The committee used the Ohio Department of Health database, specifically the mortality dataset and the deaths related to opioids. Using temporal trend analysis, the members looked at the quarterly opioid overdose death rates from Quarter 1 of 2010 to Quarter 2 of 2020.

What happened in 2020 may be considered a potential fourth wave, he said. “The pandemic may have created the perfect storm with the shutdowns, social isolation and loss of jobs that may have contributed to the spike.”

The data that are driving the committee’s targeted plans to combat the epidemic include the increased number of opioid deaths attributed to fentanyl, the Ohio counties where the most number of deaths are recorded and the pharmacophore rule that addresses the change in the structure of fentanyl.

According to the temporal trend analysis, the majority of opioid overdose deaths in Ohio are from fentanyl, which is why the committee is focusing most of its efforts on fentanyl rather than other opioids such as heroin, oxycodone and hydrocodone.

“When we look at fentanyl’s core structure, the pharmocophore, the issue we have is that we don’t see just fentanyl, we see other forms where the chemistry is changed. In Ohio we’ve seen over 20 different forms of fentanyl,” Sprague said. “What makes this so dangerous with these new chemical combinations is that they have not been tested in clinical trials, so we don’t know their overall potency. We don’t know if they respond well to Naloxone,” the medicine that can reverse an opioid overdose.

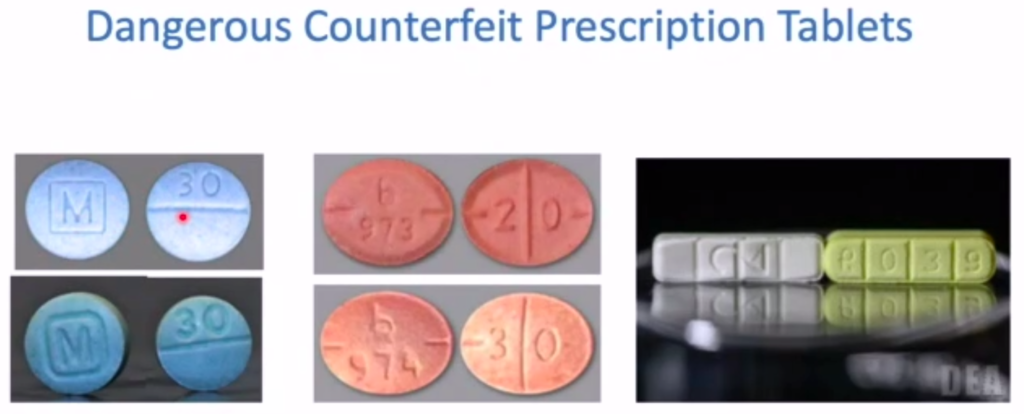

Counterfeit prescription tablets, which are made to look like a prescription tablet but may contain fentanyl or a combination of agents that can lead to respiratory depression, are also huge contributors to opioid overdose deaths. They are easily purchased from dealers or directly on the internet, and often folks don’t even know they are being exposed to fentanyl when they purchase these counterfeit tablets, he said.

“With all the bad news about opioid overdose deaths, what are we doing to combat it?” Sprague asked. ”My team was reviewing the literature, looking at monitoring trends in opioid deaths, and monitoring new chemical molecules as they came out.” From there they developed the target areas for Ohio.

A study conducted with healthcare programs in the state set out to determine how students in medical, pharmacy, nursing, physician’s assistant and dentistry programs were being trained in substance abuse and opioid use disorder. They identified six focus areas and developed a course last spring that is now being taught throughout the year. The course includes an escape room model where an interdisciplinary healthcare team works through a case to get a dose of Naloxone to save a patient.

Together with the Drug Enforcement Administration, the committee addressed the importance of opioid storage and disposal. They enhanced the number of drug drop-off days in the counties that had previously been identified as having the highest opioid drug overdose deaths. In Scioto, Fayette, Franklin, Clark, Montgomery, Trumbull and Mahoning counties more than 1,500 pounds of drugs were collected through the increased efforts, Sprague said.

For the third target, the committee is developing a behavioral-economic approach to teach students in grade school and middle school how to make decisions to do something or not to do something.

Pharmocogenetics, abbreviated as PGX, is the fourth target area. “We wanted to look at what genes might be associated with the development of opioid use disorder and in doing so, we were hoping to develop a genomic opioid addiction risk score. If you have to have a knee replacement surgery, potentially we could screen for one or two specific genes and stratify patients who are at high risk to best manage their pain and avoid development of opioid use disorder,” Sprague explained.