By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

No one comes out looking well in the invasion of Iraq. Not Saddam Hussein. Certainly not George W. Bush and the various members of his administration. Nor for that matter some of the critics of the war.

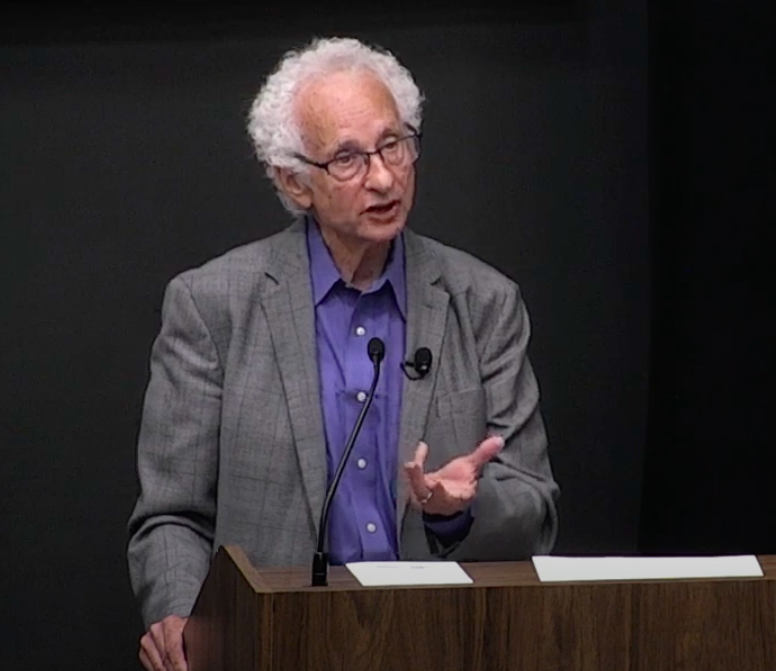

In October, historian Melvyn P. Leffler, of the University of Virginia, delivered the Gary R. Hess lecture on campus. He spoke about his book “Confronting Saddam Hussein: George W. Bush and the Invasion of Iraq.”

Unlike his earlier work, Leffler noted, this book does not rely heavily on U.S. government documents. Many of those dealing with the Iraq invasion are still classified. Instead, the historian conducted extensive interviews with the policy makers who helped shape the policy – former Vice President Dick Cheney, Paul Wolfowitz, Scooter Libbey, Donald Rumsfeld, and Colin Powell.

The one person who refused to talk to him was George W. Bush, who had Leffler said, the final word when it came to the invasion.

Some critics have said he was “sucked into believing” these policymakers take on the invasion. But Leffler did have access to the documents made public through the inquiry by the British Parliament into Great Britain participation in the war as well as Iraqi government documents seized in the invasion. And he relied on those just as much as the interviews.

“The invasion of Iraq was probably the most consequential foreign policy decision since the end of the Cold War,” he said. And it resulted in tragedy.

More than 200,000 Iraqis died in the war and the insurrection that followed. Approximately 9 million people were displaced. About 9,000 members of the American Armed Services and U.S. contractors perished in Iraq. And the U.S. involvement in Iraq cost $2 trillion dollars.

“My purpose is not to indict the administration or acquit it,” Leffler said. “I try to understand why things happened as they did” and why policy makers made the decisions they did.

His conclusions are damning. “This is a cautionary tale. George Bush went in with the best of intentions, but a lack of preparations,” he concluded.

While the planning for the invasion was “exquisite,” Leffler said, little thought was given to what would happen afterward.

He attributed that to hubris. “American decision makers felt that American forces would be embraced by Iraqis … that people elsewhere wanted to emulate the American system of democratic capitalism.”

This led to an American policy that “ignored the sensibilities and values of Iraqis themselves,” he said.

Despite what some critics of the administration claim, George W. Bush didn’t come into office planning to invade Iraq, in part to avenge Saddam Hussein’s plot to assassinate his father, the former president George H.W. Bush on a visit to Kuwait. Nor was it to control Middle East oil or spread American democracy, though he hoped that would result.

The younger Bush inherited a policy of promoting regime change in Iraq from the administration of Bill Clinton.

The catalyst for the invasion was the terrorist attack on the United States on Sept. 11, 2001. “His overriding motive was to prevent another attack,” Leffler said.

There was a sense of fear, a belief that another attack was being planned.

Without that attack there would have been no invasion. Without Saddam Hussein’s recalcitrance to cooperate with the international community to show his country did not possess weapons of mass destruction, there would have been no invasion.

While the United State reeled from the attacks, Saddam “gloated over 9/11.” He was the only international leader who did not express condolences.

Bush was appalled and embarrassed by the attacks, and he feared another one, both because of the damage to the country and for the political ramifications.

Firs came the invasion of Afghanistan which harbored al-Qaeda, the terrorist group that carried out the attack.

But Saddam had supported terrorists and backed suicide attacks. He was also believed to have stockpiles of chemical and biological weapons, and to be developing nuclear weapons. He didn’t cooperate with the international inspectors looking at those claims. And the administration feared he would share those with al-Qaeda and other terrorist groups.

Nor was the belief that he had chemical weapons and would use them unfounded. He already had used them against his own Kurdish citizens and against Iran. And he had lied repeatedly about these programs.

While planning for an invasion began in late 2001 that didn’t mean a decision to invade had been made. The administration hoped to initiate an overthrow of Saddam with strategic deployment of troops. It hoped that it could get the Iraqis to allow the international inspectors back in. This “coercive diplomacy failed.” And though the intelligence was ambiguous, Leffler said, the Americans invaded.

“As I researched, I became more emphatic and more critical,” he said. “I came to understand the fears and emotions that gripped the policymakers, the apprehension, the anger, the embarrassment, the great sense of responsibility.”

Leffler was shocked, however, by the poor planning and the unwillingness to reexamine key assumptions and the aversion to engage in hard thinking about the consequences of an invasion. “Those shocked me and still do.”

The Iraq war proved to be a foreign policy disaster leading to “a long litany of dire consequences.”

It enhanced Iranian power in Persian Gulf. It diverted attention and resources from the intervention in Afghanistan. It created a rift between the U.S. and important allies including France and Germany. It provided opportunities for China and Russia.

The invasion and occupation fueled the sense of grievance among Muslims and heightened anti-Americanism throughout the Middle East and the world.

The war complicated the global war on terrorism.

Domestically the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq accentuated the partisan riffs and undermined the trust of the American people in their own government. “The current distrust of experts and expertise,” Leffler said, “stems from the errors leading up to this war.”