By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Geraldo Rivera gave his audience a choice: Was Judith Schaechter’s stained glass window “Rape Serenade “ art or smut?”

He was taping an episode, “From the Renaissance to the Revolting.” So, he asked the audience whether the piece depicting a clown with a quizzical expression on his face assaulting a prone man with a couple of his fellow clowns looking on was this art or smut?

Based on the applause meter, they responded that it was art.

“That’s not good,” Schaechter told reporters and museum staff during a press preview on Friday. “I definitely want to be smut.”

Now that piece is one of 45 pieces on display at the Toledo Museum of Art in “The Path to Paradise: Judith Schaechter’s Stained Glass Art,” which opened today and runs through Jan. 3.

“Early on I wanted to make things that were shocking but also beautiful,” she said. That includes a piece on infanticide. The stained glass window was inspired when Schaechter wrote a review of an encyclopedia on female mass murderers. Schaechter realized women who committed mass murder are either nurses who kill their patients or, like the figure in the art work, mothers who killed their children.

The juxtaposition of the ugly and the beautiful is a thread that runs throughout the exhibit.

When she was a child, Schaechter said she was teased about her big nose. The other children called her ugly. When she went home and sought her mother’s consolation, neither her mother nor her grandmother would tell her “no, you’re gorgeous.” Instead they’d say “don’t listen to them” or “pretty is as pretty does.”

So, in some “reptilian” part of her brain, she decided “if couldn’t be gorgeous, I would make gorgeousness.”

She likened beauty to cheese. “There’s a little bit of rotting death in every bite,” she said, and then you want more. Cheese without this, Schaechter said, is Velveeta, which is only pretty.

The artist said that growing up in Newton, Massachusetts, she was always an outcast.

Her mother was from Oklahoma. “She was desperate to be from somewhere else and be a classical pianist. Instead she became a social worker.”

Her father was Jewish. He grew up in Milan, Italy, and fled the Nazis during the Holocaust. Because the United States was not taking in Jewish refugees, his family ended up in Ecuador.

This mixed heritage meant Schaechter didn’t fit in with any social group. Her brother suffered from a mental disability. He couldn’t talk. “It was like living with a wild animal.” No one wanted to come to her house.

And her parents were Socialist. “We were just weird,” Schaechter said, “and when you’re weird you grow up to be an artist.”

Her parents were “incredibly supportive “of her pusuit of an art career.

She went to the Rhode Island School of Design to become a painter. But her teachers discouraged her from doing figurative work.

She was told: “Go sit in front of your canvas and have a creative moment. That sounds horrible.”

Most of what she produced “ended up in the garbage pail.”

But, the stained-glass studio was right next to the painting studio.

Schaechter does not know what drew her to stained glass. Still, “it was so compelling it changed my whole life.”

Yet even after graduating from RISD and moving to Philadelphia, she pursued painting. It took her a few years, to be drawn back. “I really missed stained glass.”

At art school, she was blunt about the fact that she longed to be famous, and the response was that she was a sellout. On the other hand, “I never dared to dream that anyone would ever take me seriously as an artist,” she said.

“I don’t think a great recipe for success is being a female artist from Philadelphia who insists on working with stained glass. If you want to be successful don’t do that. … The other part that resonates with non-success is make your subject matter screaming women,” adding wryly “that’s going to take you to the top right away.”

“Path to Paradise” is a celebration of almost four decades of success. She turns the ancient art form so associated with sacred iconography to her own contemporary and profane uses, with allusions to classical art and popular culture.

On arriving the viewer confronts the large scale “Battle of the Carnival of Lent” created for the Eastern State Penitentiary Historical Site. The window is the largest, Schaechter has done. She was reluctant to take it on, even though or maybe because, she was told it would be her masterpiece. When she did, working on it ruined her life, Schaechter said. She had not time for anything else.

Inspired by Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s similarly named “The Fight Between Carnival and Lent,” Schaechter envisioned the seven deadly sins versus the seven cardinal virtues. But, “I don’t really believe in black and white like that,” though she depicts an angel and devil at the top of the window.

Instead, it became a battle of someone imprisoned psychologically “where the battle for impulse control has clearly been lost,” she said.

“I think about what these pieces mean when they’re finished,” she said. “I don’t think about it at the beginning.” When she looks at the final work it’s “in the spirit of ‘Oh, my god, what have I done.’”

She can have an image, for example, that of a woman in repose on a couch in “Nature,” which is in the Toledo Museum’s collection, waiting for the right setting.

Using Photoshop, she tried pairing it with more than hundred other images, finally arriving on the contrast between cut flowers and the profusion of flowers growing outside a window.

The woman’s demeanor is perplexing – what is she feeling?

This was inspired by the writings of a psychologist who believed, Schaechter said: “You can’t tell the difference between when someone is in orgasm or whether they are being tortured. It’s the same face.”

This was something she instinctively knew.

Now 59, she admits to sometimes being concerned about running out of steam artistically. “I can’t have any more ideas because my neural pathways are calcified into these giant ruts and I have to go down the same rut every time.”

Then she doodled a drooping flower that blossomed into the “The Florist,” with a female figure, originally meant for another piece, with her head down on a table, surrounded by the drooping flower in vases.

“The Florist” is an example of how the artist makes things as hard as she can for herself. Originally each vase would have been one of four designs. Instead she created 30 different goblet designs.

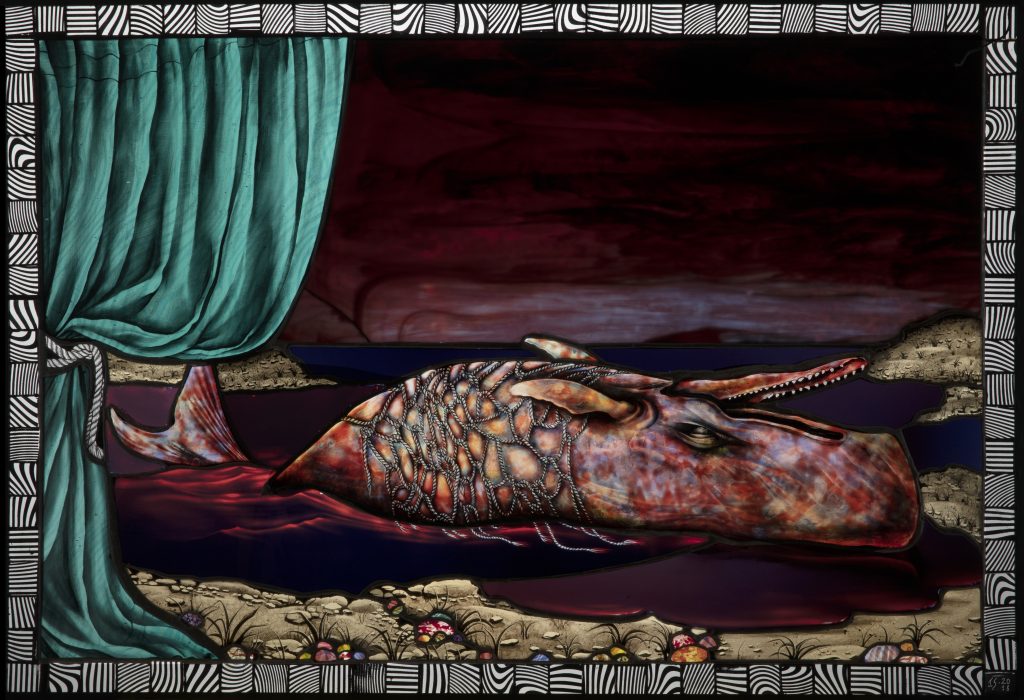

The final image in the exhibit is “Beached Whale” from 2019. The mammal is wrapped in a fishing net, and in the foreground a theater curtain is drawn aside to reveal the scene.

The window reflects Schaechter’s concern for the environment, and what humanity is doing to it and their fellow creatures. She expects to work more along these lines.

“I deeply believe that all art can be seen as political,” she said, “especially anti-fascist statements. Because if one consciousness asserts itself somehow that’s a blow to the empire.”

Schaechter’s ability to turn a phrase is also on display in “Path to Paradise.”

Quotations from the artist are emblazoned on the walls throughout the exhibit. One states: “Stained glass is dead! Deader than dead! Long live stained glass!”

“The Path to Paradise” is an affirmation of that stained glass is indeed alive and well in Schaechter’s work.