By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

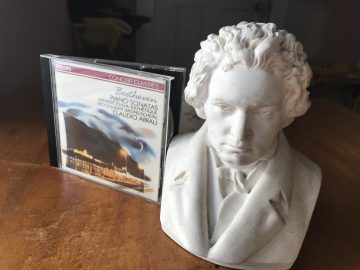

Robert Satterlee and more than 20 of his pianist colleagues are ready to roll out the Beethoven to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the composer’s birth.

By the time the actual anniversary rolls around on Dec. 16, 2020, Satterlee and friends will have performed all 32 of Ludwig Von Beethoven’s piano sonatas, as well as his Diabelli Variations in a series of 10 Sunday recitals at the Toledo Museum of Art.

The first recital, part of the museum’s Great Performances series, will be presented Jan. 12 at 3 p.m.

Satterlee organized the series. The anniversary seemed a good time to perform the entire cycle of sonatas. “They’re at the heart of what we do as pianists,” Satterlee said. “They’re such great pieces. They’re like a diary of Beethoven’s life. … Of all the genres he wrote in, this was really important to him.”

Still Satterlee, who is on the piano faculty at Bowling Green State University, said he knew he didn’t want to perform all 32 himself. That would be three years work to prepare.

So he reached out to his colleagues in the region. “My intention was to play more, but other people were interested in playing. I thought it’d be great to include as many people as possible.”

So he’ll end up playing the “Pathetique,” Opus 13, one of the most famous on the second recital on Jan. 26 and he will conclude the series on Dec. 6 by playing the “Diabelli Variations,” not a sonata, but a “crowning piece “ for solo piano.

He was surprised no one else had expressed interest in performing “Pathetique.”

“That’s the most famous Beethoven. Every talented high school student plays that. It’s a rite of passage.”

The sonatas will be performed in chronological order.

Sunday’s inaugural recital will feature the three sonatas in Beethoven’s Opus 2 performed by Matthew Bengtson of the University of Michigan faculty and two of his graduate students Gabriel Merrill-Steskal and Shuntaro Sugie.

These will be performed on a piano-forte, a replica of the instrument Beethoven would have used.

The sound of the piano forte is softer and clearer, Satterlee said.

The recital will conclude with Kate Boyd, from Butler University, playing Opus 7 on a modern piano, so listeners will be able to compare the sounds of the instruments.

Bengtson will return on May 31 for another recital featuring the piano-forte.

These early sonatas were composed for the composer to perform, and they were influenced by his improvisations. “That’s what he was known for in his lifetime,” Satterlee said.

Concerts then were not like these recitals that will celebrate him. The performers played music that was at most a few years old, and there would be a mix of performers, maybe a singer, and string quartet.

Beethoven would play a couple composed pieces, and then he would improvise on a popular theme, a folk tune or opera aria.

“By all accounts his improvisations were long, and people commented how incredibly emotional they were, and just as well formed as the pieces that were written,” Satterlee said.

So when a pianists plays these now, they should play them with that same spontaneity.

Satterlee recalls: “When I was young, sometimes I didn’t like Beethoven. Some of the things are awkward for the instrument. … It’s a struggle. You have to play a lot of Beethoven to understand that the way he wrote for the instrument could only be that way. He wrestled the notes into the shape he wanted, and it didn’t always fit the hands.”

Satterlee started taking piano lessons at 11. He was fascinated with the piano long before that but his family didn’t own one. His mother had played piano through college and the family had an electric organ. But that wasn’t the same.

“It’s weird how the bug takes hold,” Satterlee said. Growing up in northern Montana, his parents had a large collection of records including pop, folk, classic. “I just really gravitated toward the classical piano.”

He remembers listening to snippets of Beethoven sonatas, including the “Pathetique” adagio on a record of great classical piano themes.

Then friends who were moving needed a place to store their piano. So at 11 he started with a local teacher, and when she retired he traveled to Missoula to take lessons, eventually with Dennis Alexander, now known as a prominent composer of instructional pieces.

Satterlee said throughout he was fortunate to have “first rate teachers who were very supportive and enthusiastic,” he said. “You could tell they loved the arts.”

Satterlee said his parents never had to nag him to practice. “I really wanted it. I was really self motivated.”

By his junior year in high school he knew piano was what he wanted to pursue.

And Beethoven has continued to be part of that.

“Playing Beethoven makes me a better person,” Satterlee said. “It’s kind of like seeing a play by Shakespeare, it’s entertaining but also shows the nature of truth, the nature of beauty.”

While there are some sonatas less frequently played, pianists do have niches of the repertoire that they explore.

The last sonatas were not played in Beethoven’s lifetime and long had a reputation of not being very good because of their difficulties. They only came into their own when Artur Schnabel recorded them in the 1930s as part of the complete sonata cycle.

The 40-minute long “Hammerklavier,” Opus 106, is considered a particular challenge. “That’s a piece we all approach with great trepidation. It’s like the Mount Everest of the piano repertoire.”

The piece is scheduled to be performed by University of Michigan graduate student Mi-Eun Kim on Oct. 25, the third from last concert in the series.

“Beethoven encompasses the entire human experience, every human emotion, every feeling, every situation,” Satterlee said.

“It’s also so well constructed. He takes simple musical idea and builds very complicated and interesting structures. There’s so much variety among the sonatas.”

Each is unique. “It’s repertoire that repays endless study.”