By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

A hundred or so farmers listened to the grim reality last week that they need to do more to prevent algal blooms in Lake Erie.

A panel discussion hosted by the Ohio Farmers Union at Otsego High School stressed that while some farmers are voluntarily reducing the phosphorus that creates the harmful algae, their efforts are not likely to be enough to meet the federal goal of a 40 percent reduction. And that means if farmers don’t make the necessary reductions on their own, they may be forced to do so.

“We know that farmers need to do more,” said Joe Logan, president of the Ohio Farmers Union. “Farmers need to stand up. They always have before, and I believe they will again.”

The alternative is that the Environmental Protection Agency will get involved and set stricter requirements. “If we don’t achieve that, there will be additional regulation,” Logan said. “Farmers need to up their game in terms of the environmental repercussions.”

Jeffery Reutter, retired director of the Ohio State Stone Lab, said the 40 percent reduction is only possible if extensive changes are made, and if problem fields are identified. But he also predicted that one-third of farmers are not likely to take needed action without “more aggressive encouragement.”

When asked by moderator Jack Lessenberry about the best ways to reduce phosphorus in Lake Erie, the panel had varied answers.

Meindert Vandenhengel, who owns a 5,000-head hog farm in Van Wert County, said the only problem is distribution of manure. There is plenty of farmland to handle all the manure, it just needs to be spread properly.

But Vandenhengel seemed to be aware of the perspective of people in the Toledo area, who may think, “I buy his pork chops, but he’s poisoning my water,” he said.

Logan said rigorous soil tests must be performed and application regulations must be set.

“There are enormous economic incentives to take shortcuts,” Logan said of the agricultural industry. “We need absolute limits to application rates.”

Reutter said farmers need to apply less phosphorus and the amounts they do apply should be inserted into the soil to prevent runoff.

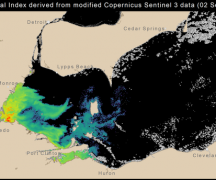

Reutter explained that western basin of Lake Erie is most susceptible to toxic algal blooms because of its shallow depths, the high use of agricultural land in the watershed, the lack of forested land, and the urban/suburban areas. The Maumee River drains 4.2 million acres of farmland into the lake.

“That means we’re going to get the most nutrients,” he said.

The algae problem is not new – having occurred before in the 1960s and 1970s. But the region recovered then by improving sewage treatment plants, reducing phosphorus by 62 percent, Reutter said.

But that was an easier fix back then. Rather than working on sewer treatment plants, “we have thousands of farms,” he said.

Fixing the problem is also made difficult because many farmers won’t accept their role in the solution, some panelists said. Though the Detroit River may pump a lot more water into Lake Erie, the Maumee River is pumping a lot more phosphorus.

“We can tell how bad the bloom will be,” by measuring the phosphorus in the Maumee River from March 1 through the end of July, Reutter said.

Research has shown that sewage treatment plants are not a big part of the problem.

“Sewage treatment plants don’t vary much” with the weather, Reutter said. But heavy rains send much of the phosphorus on farm fields into waterways and eventually to Lake Erie. “Every place we have a high concentration of agriculture, we have algae blooms.”

“Farmers import a great deal of phosphorus into this watershed,” he said, with much of it remaining in the soil for years. “They are going to bleed phosphorus for years even if we don’t put on any more.”

Greg Labarge, of the Ohio State University Farm Extension, said farmers need to use science-based operations focusing on edge field monitoring, water control, water filtering and erosion. Farmers need to focus on nutrient application rate, timing and placement – and ideally apply it below the surface of the soil.

Verna Harrison, a conservation leader in the Chesapeake Bay Region, talked about how that area cleaned up its water by adopting a federal limit on pollution that could enter the waterways. Though many in the agricultural community were worried about the effects, it did not harm farming operations, she said.

The program put agriculture, environment and government officials together to solve the problem.

Like the Lake Erie basin, the Chesapeake Bay is shallow and surrounded by farm production.

“But you have a much more potent human health risks,” Harrison said of the Lake Erie algae issue. “People are really getting worried about this.”

Making the problem even more difficult are the proposed cuts to the EPA in President Donald Trump’s budget. His proposal eliminates funding for Lake Erie and makes cuts to agricultural programs.

If that happens, “Lake Erie goes back to where it was in the 1970s,” Reutter predicted.

Eleven million people could no longer look to Lake Erie for safe drinking water, he said.

“It’s very puzzling to me to see those cuts,” Harrison said, since voters did not seem to be giving a mandate to get rid of clean water and clean air.

Logan predicted that safe drinking water and the economic value of having a healthy lake will win out. “There are commercial forces at work here,” he said. “They will be a compelling reason for us to make changes.”