By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Historian Rebecca Mancuso is a Bowling Green native. She grew up here and got her first two academic degrees at Bowling Green State University where she now teaches.

So she knew about the fingers in the jar, the macabre artifact of a woman’s brutal slaying by her husband in 1881. “I’ve been fascinated by the fingers all my life.” She recalled begging her parents to take her to see them.

When she asked those assembled at Jerome Library to hear her talk “The Finger Saga: One Museum’s Quest to Turn the Macabre into the Meaningful,” how many people had seen the fingers, an overwhelming number of people raised their hands. “Bowling Green folks cherish the fingers,” Mancuso said.

One woman remembered running up the stairs to the fourth floor of the county court house where they were displayed until 1980.

Willis Beck, a long-time member of the Wood County Historical Society which now owns the fingers, said people visiting the courthouse to pay their taxes were extra careful about handing over the correct amount because they saw the fingers and thought “they mean business here.”

Too often, Mancuso said, the fingers, which were taken off display in 2014, were reduced to a sideshow curiosity or a punchline.

But Mary Bach was a real woman who met a tragic end. Her murder has echoes in the present. The circumstances of her murder are the same as those of domestic murders today, the historian said.

Mancuso’s presentation was based her journal article published last year in The Public Historian. The article won the BGSU Center for Archival Collections’ Local History Publication Award in the Academic Scholar category.

The article, she said, was intended to reflect the discussions about the fingers held at the historical society, where she served as a board member. It would serve as a guide to other museums dealing with human remains.

“I do not speak for the museum,” she said. Museum officials make the decisions about how to handle the fingers and other holdings.

The museum director Kelli Kling and her predecessor Dana Nemeth were in attendance, and Mancuso shared recent correspondence she had with the curator Holly A. Kirkendall

In her research, Mancuso found that the fingers in the jar are an anomaly among museum displays involving human remains. Mary Bach is not anonymous. We know a lot of about her life, and even more about her death in 1881.

Yet her presence had all but disappeared in a haze of sensationalism and the story of her husband.

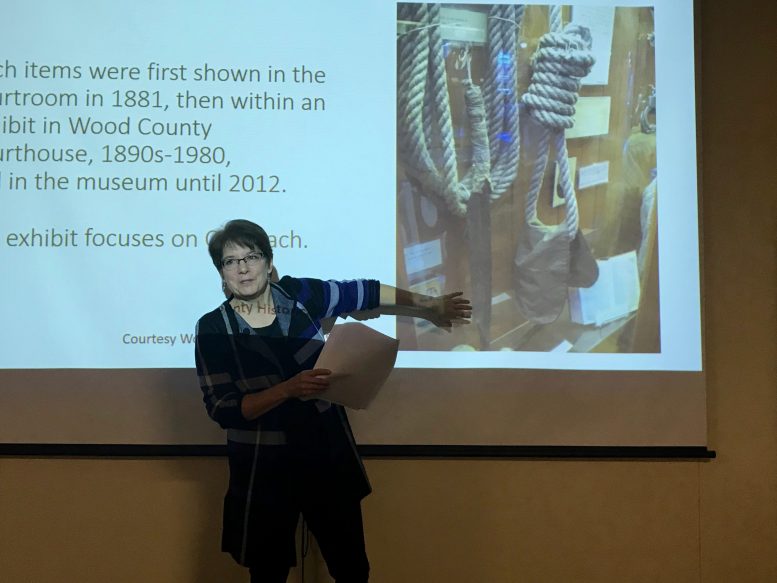

The items, plus a bloody bedsheet, which no longer exists, had been presented as evidence in her murderer’s two trials. They focus on the husband. Shown were the corn knife he used as the murder weapon — he said “came into my hand,” alongside the noose and hood from his execution, his pipe, and his Bible. The fingers were all that represented Mary.

This disturbed staff members and people in the community, especially women.

So after much consideration, when the fingers are again displayed in May, 2020, they will be presented in a new context.

They will be used to draw in visitors, and the focus will be on Mary. The fingers can be an interesting way to begin the conversation, Mancuso said, about the issues surrounding her death.

“We want to put Mary Bach at the center of the story and give her an autonomous place in history.”

Her story will be told through a victim impact statement. The museum will partner with the Cocoon, and include video statements from contemporary victims of domestic violence.

The museum will also draw on the resources from the local chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness and the county Alcohol, Drug Addiction and Mental Health Services board to provide information for people who are dealing with violent tendencies.

“The constellation of factors” surrounding Mary Bach’s death are still “the factors that increase the chance of a woman being killed,” Mancuso said.

Those are financial strain, previous abuse, pregnancy, a perpetrator who adheres to strict gender roles, and a woman attempting to leave the abuser.

“We can connect past with the present,” Mancuso said. And the lure of the fingers can help draw people into a serious consideration of those issues.

The fingers do bring visitors to the museum, she said. People would show up specifically to see them. The museum is considered a dark site because of its connection to what a newspaper at the time called “the most shocking butchery in the history of the county.”

Human remains are a major draw to museums around the world, Mancuso said. She noted the popularity of touring exhibit Body Worlds in which flayed, plasticized human corpses are posed playing tennis or doing other every day activities.

“If a museum has human remains, it’s a real attraction,” she said.

She consulted with other museums including the Holocaust Memorial Museum, Jamestown Rediscovery, and a medical museum on their approaches to handling human remains. In each case it varied based on the remains and the mission of the institution.

Beck noted in the early years those who ran the historical museum weren’t professionals. They gathered up old objects and then told stories about them.

In the case of the fingers, those stories weren’t necessarily accurate.

When Nemeth was a guide in the 1980s, she was told that she may mention that the child Mary was carrying may not have been her husband’s.

Mancuso said that “looking through all the documents I find no proof of that.”

But Mary was not around to tell her side of the story. So while the press portrayed her sympathetically at first, in the two years between her death and her murderer’s execution that changed.

She was described slovenly and lazy and unwilling to fulfill her wifely duties. In a story in the Sentinel-Tribune right before his execution, Carl Bach was described as a “pitiable man and a poor victim whose wife was more a burden to him.”

Now with the museum’s help Mary will have a chance to set the record straight.