By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

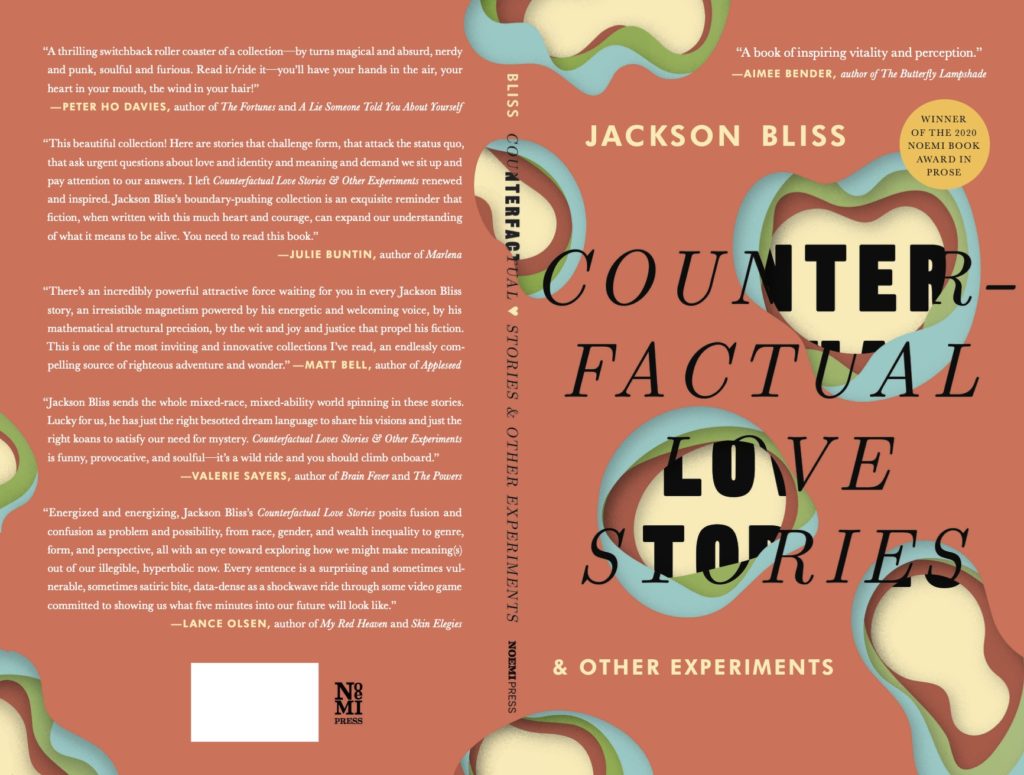

Jackson Bliss was looking forward to his collection, “Counterfactual Love Stories & Other Experiments” being published by Wayne State University Press in their Made in Michigan series.

The book would provide, he said, a different view of the state, with its multi-cultural, mixed-race cast of characters and concerns. That’s unusual for a literary novel set in Michigan.

Then he received the Noemi Press Book Award, and it was an offer he couldn’t refuse. He was honored by the prize that includes publications from an imprint he greatly respects.

So, “Counterfactual Love Stories & Other Experiments” will be published next year, the first in a burst of publication for the Bowling Green State University faculty member. Click for ordering information. Also forthcoming is a memoir, “Dream Pop Origami” and a novel, “Amnesia of June Bugs,” both in 2022. Bliss teaches creative writing and literature at BGSU.

Bliss has roots in Michigan, but more importantly a global vision. A story may be set in Ann Arbor, but the characters always have their hopes pinned on a distant horizon. In the story, “The Day We Never Met,” the two lovers, Minato and Rumi, never do intersect. They do not end up living in a spacious two-bedroom apartment close to Trader Joe’s. Instead their destinies take them to Iran and Azerbaijan, which made them neighbors, in a way. It’s another kind of satisfying ending.

Bliss’s experimental fiction, with its wry interludes and occasional self-deprecation, is full of these possibilities that sprout from his detailed portraits of urban life.

Bliss grew up in Traverse City. His mother and Obāchan (grandmother) had immigrated from Japan; his father is from Dearborn, Michigan and is of French, English, and Irish descent.

His Japanese side seems “very fresh.” He has visited relatives in Japan. “That’s why you see so much of the Japanese side in the writing,” he said. The European ancestry is “very diluted.”

His grandmother would not speak Japanese to him. “She wanted make me 100 percent American,” he said. “A lot of what we gave up to survive I had to rediscover as an adult.”

He did learn to speak “basic” Japanese. “I’m the linguistic equivalent of a 10 year old.” He is fluent in French and Spanish.

Though he still has friends in Traverse City, he said, “I found it oppressive as a mixed race person.”

Bliss understood as a child, the condescending attitude toward his Obāchan by the women who employed her. “I knew what those smiles meant.”

“Even when I was teenager I wanted to get to hell out of Traverse City,” he said. Others of Asian ancestry was eager to assimilate.

Then one day in eighth grade, he was in a diner with some friends when a group of other teens came in. He could tell by their clothes and their talk about travel and culture that they weren’t from Traverse City. They were from the Interlochen Arts Academy, which is south of Traverse City. “These were people who would open up my world,” Bliss said.

Bliss spent a year at Interlochen Arts Academy as a piano major before his family moved to California and later to Chicago. He attended Oberlin where he studied comparative literature, and began to write. He wrote fiction and essays as “a reaction to loneliness and isolation and alienation.”

At Oberlin, he missed the multicultural energy of Chicago. “It was my first response to being away from the world I knew.”

His characters were “racially and culturally alienated from the world in which they lived and that was a good summary of how I felt being at Oberlin.”

So, in fiction he created the world he wanted to live in.

It would take him time and travels and more study before he settled down to being a writer. He moved a lot. He studied East Asian language and Buddhism at Yale. He taught English in Burkina Faso.

He was living in Portland when he started attending fiction writing workshops at Portland State University.

That’s where the work in “Counterfactual Love Stories” started taking shape.

One story was the first draft of what became “Sola’s Asterisk.” That early draft was 58 pages long, Bliss remembered.

In the story she confronts a daunting intersection and eight different destinies. She explores each of them and in the course we get a taste of book shops, clubs, restaurants, and the diverse people who inhabit them. She finds sex, and in the end love … that’s where the library comes in.

The author’s love of the urban resonates throughout the book. “I’m just one of those people who needs the energy of the city.”

In “French Vowels Make You Look Like Goldfish,” he explores teenage rebellion through language.

Shigeru, like Bliss the son of an American father and Japanese mother, rebels by only speaking French, a language neither of his parents speak.

They must rely on the translator Jean-Luc to come and mediate their disputes.

The language and culture gave Shigeru an avenue to learning “other ways you can perform as a man,” Bliss said.

That was true for him as well. His exploration of his own French heritage allowed him to see there was more possible than the Midwest template of either being on the football team or in a rock band.

Throughout “Counterfactual Love Stories,” Bliss toys with ethnic stereotypes. They reflect “a racial discourse that existed before you were born” against which a person must shape their identity.

For Bliss that identity is transnational. When he taught English in Burkina Faso, he had to do it in French, the official language of the former French colony. It was surreal, he said. “”Basically, using French to explain English grammar to students whose first languages isn’t even French was a very bizarre process.”

Yet seeing language this way makes the speaker realize how elastic their native tongue is, how “elegant, smart, arbitrary and bizarre and confusing.”

Later after earning his Master of Fine Arts in Writing at Notre Dame, he went to live in Argentina.

Even when he writes about a specific place there are border crossings involved. People remember living somewhere else, or dream of it.

“Living outside of America gives them a right to redefine and recreate themselves. I see the transnational narrative in some ways as a metaphor for parallel lives in a different city, a different culture …. because you’re basically changing all the rules of existence.”

That’s clear in the way Bliss transcends the rules of traditional narrative.

The “skill set” that makes a good expatriate, a deep desire to understand people and their culture, Bliss said, “is the same for becoming a deeply empathetic imaginative writer.”