By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

When Sandra Faulkner wanted to study women runners, she used poetry as well as footnotes.

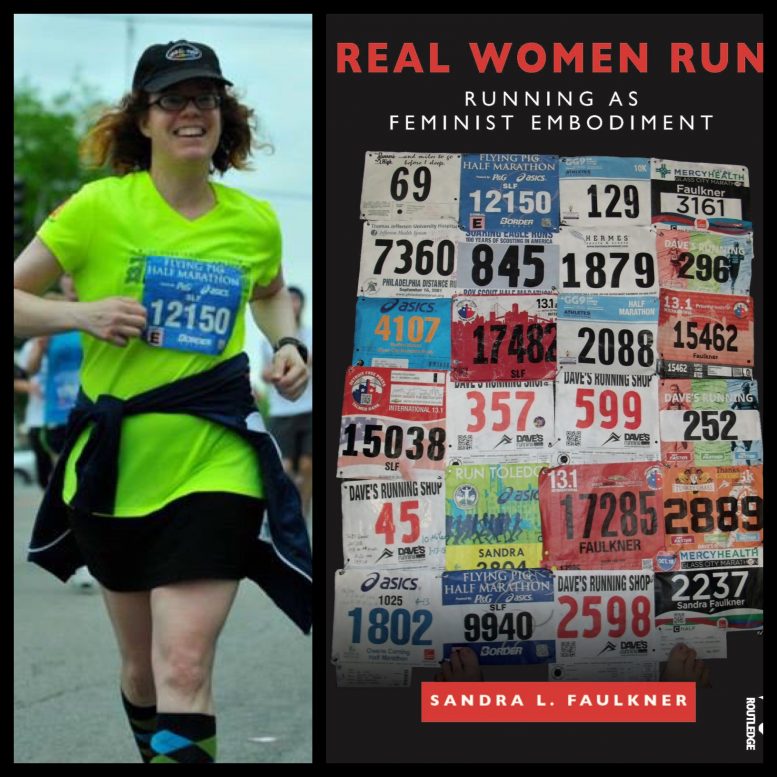

Earlier this year, Faulkner, a professor in the School of Media and Communication, published “Real Women Run: Running as Feminist Embodiment.”

The book is deeply personal scholarship. Early on Faulkner traces her own history as a runner, starting when she was 11 years old, growing up in the suburbs of Atlanta. She ran so hard her nose started bleeding. She didn’t notice until she finished the race, and won third place. But she missed the awards ceremony because her mother couldn’t staunch the bleeding.

Her life as a runner has been full of small triumphs, injuries, and frustrations – sometimes at the same time. Though Faulkner says she doesn’t race to place, she’s still competitive. After one race she saw that she was fourth in her age group, but she thought there were only four runners in that class. Only later didn’t she learn there were more than that.

Her life as a runner is told in brief journal-like entries, and each is paired with a haiku. One reads: “Don’t call us a girl / don’t call us a girl jogger / fierce women running.”

The personal stories are “in service critiquing, discovering, uncovering larger social patterns,” she said.

They take us up to Sept. 3, 2016, when Faulkner is 44 and has a daughter of her own, who cheers on her mother and herself has started running. “She’s more of a sprinter,” Faulkner said.

This was the right time for Faulkner, an ethnographer, to research women and running. She would never have done this as a dissertation. When she used interviews for her dissertation on Sex and Sexuality at Penn State, where she studied interpersonal communication, it was considered unconventional.

But when “Real Women Run” was starting, Faulkner had tenure and was taking the next step of applying for promotion to full professor. She had already completed a much cited book on poetic inquiry, “Poetry as Method: Reporting Research through Verse.”

“I’m convinced that this book wouldn’t have happened until that exact point.”

BGSU, where she’s been on faculty for 11 years, was the place to do it. “BGSU has been a great place for me.,” Faulkner said. “I have felt very supported in my work. I think this is my best work. I feel very satisfied and pleased.”

Last fall, she coordinated an international conference on poetic inquiry on campus. It was held in conjunction with the annual Winter Wheat writing conference. She’s collaborating with Abigail Cloud, of the creative writing faculty, on an anthology of poetry of a more political nature.

“There’s things that poetry can do that other forms of writing can’t, especially since I was interested in the embodied experience of running,” Faulkner said. Embodied experience with no “false separation between mind and body” is a hot topic in feminist theory. “I think poetry can do that in a way prose cannot. … Poems are all about the line, all about the breath. When done well they can be an embodied experience.”

She interviewed 41 women runners at races around the country asking them: what does it feel like when you take a good run? What does it mean to have a bad run? Why do they run?

Faulkner speculated that women’s interest in running got a boost when Oprah Winfrey ran the Marine Corp Marathon in 1994. Now more women enter road races than men

There are many reasons for that. Some run for health. Some for losing weight. Some for stress relief. Or some for personal growth.

Faulkner said that running gives her a personal space, away from being a professor, a mother, a partner. “It really feels like this is something I do for myself.” Over the years running has become more meditative.

Though she’s run a marathon, Faulkner’s favorite distance is the half-marathon, and her favorite race is the Boy Scout Marathon in Bowling Green.

Her interest in poetry began when she was young as well. She wrote “bad poetry” as a child and then after a writing workshop struck up a correspondence with poet who nurtured her talent.

But as she continued her academic pursuits, verse was set aside – “then I go to grad school and it tries to kill all creativity.”

But she started attending community poetry workshops, and she began to write again. She even tried to work scholarly language into her poetry, without much success. The vocabularies proved “incompatible.”

Her poetry has been published and she’s won an award.

Faulkner hopes the use of poetry gives “Real Women Run” an appeal beyond academia, and even the running community. There’s enough about personal experience and relations to interest the general reader, who has to be neither a runner nor an academic, to appreciate the book.