By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Banning books never seems to go out of style.

Charles Coletta

To make that point, before Charles Coletta started his talk “The Seduction of the Innocent: The Anti-Comic Book Crusade of the 1950s and Beyond” he listed entertainments his students in Popular Culture classes have been forbidden to read or watch. Those include Harry Potter, “South Park,” “The Simpsons,” and “Sponge Bob Squarepants,” a recent addition. Then he quizzed his audience in Jerome Library. “The A-Team” was a surprise, but “Family Guy” and “Bevis and Butthead” were staples of the do-not-watch list.

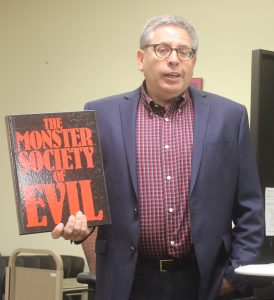

Recently the reprinting of a classic comic story

“The Monster Society of Evil,” which hasn’t been reprinted in 30 years, was canceled because some of the characterization are racist, including depictions of Japanese from World War II and stereotypes of African-Americans that are “horrible,” Coletta said.

And when just over a year ago the United Nations tried to name Wonder Woman as its fictional good will ambassador, there was an outcry over her skimpy outfits and that the superhero was not a good role model for women.

Those complaints echo what was said about her 70 years ago.

Because banning stuff never goes out of style, every year the Friends of University Libraries hosts an event to mark Banned Books Week.

Coletta’s focus on Thursday was on a crusade led by psychiatrist Wertham against comics for all manner of offenses, particularly promoting violence.

Superheroes, he said, was fascist role models who promote the idea that problems were solved with superior strength and violence. “I think Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic book industry,” he once stated.

Wertham also complained about unrealistic body images projected by female and male characters, racism, and embedded sexual messages.

Wonder Woman, he claimed, was into bondage — a claim that proved not so outlandish when it learned that her creator William Moulton Marston was as well.

But Wertham also said that her strength and independence, and hanging out with Amazons indicated she was a lesbian.

And Batman and Robin’s relationship, he said, was “like a wish dream of two homosexuals living together.”

He also said that comics were harming youngsters’ reading skills.

Wertham had a willing audience, Coletta said. The post-war era saw a rise in juvenile delinquency nothing major, the young folks were just getting into all kinds of mischief.

What they weren’t doing so much was reading comic books. From the 1930s through World War II, comic books were riding high. They got shipped to GIs overseas as diversion.

They came in all genres romances, Westerns, cartoon characters, and, of course, superheroes with Superman coming first, followed shortly by Batman, as well as Wonder Woman.

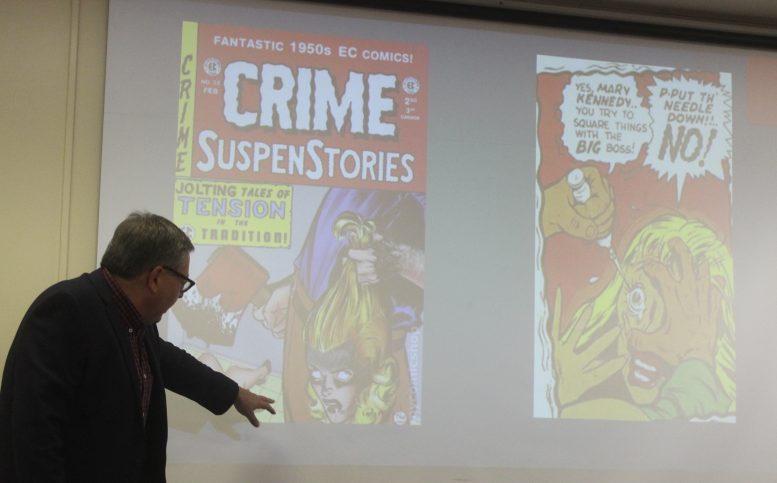

But as demand waned, publishers, most prominently EC Comics turned up the heat with horror and crime comics. Given the comic book was viewed as being aimed at juveniles this created panic.

Wertham became a pioneering talking head addressing these concerns, and he testified before Congress. Bill Gaines, whose father had founded EC Comics, had a meltdown on the stand speaking for the industry.

The hearings led the industry to adopt the Comics Code. Coletta noted that the panel that reviewed the comics was made up of women, and included a librarian, social worker, and movie script editor. They were on the watch not only for violence and sexuality, but also to make sure criminals were always punished and authority figures were always seen in the best light.

They could success all manner of charges to the comic books they reviewed. If a comic book didn’t get its seal of approval newsstands, the main retailers for the books wouldn’t carry them.

Publishers largely complied except for Classics Illustrated and Dell Comics, which felt their products did not need the extra scrutiny.

The code was abandoned by publishers, finally giving up the ghost in the early 2000s. But in the 1950s whole lines of publications died, and people were thrown out of work, Coletta said.

Gaines, though, did get the last laugh. In order to get around the code, he decided to change one of its titles into a magazine so it wasn’t covered by the code, and MAD Magazine was born.