By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

When Talon Silverhorn, a citizen of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe, arrived in Ohio, where he is an interpreter at the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks, he realized he was not in Oklahoma anymore. Back in Oklahoma where he grew up, everyone in his community was indigenous – his classmates, his teachers, the people who worked at Walmart.

Ohio, though, has far, far fewer indigenous people. But it didn’t used to be like that, he noted ruefully.

His people, along with many others, were removed by the U.S. government from Ohio more than 200 years ago.

And to many native people have been relegated to the past. He noted 87 percent of the curriculum about indigenous people ends more than 100 years ago.

But, Silverhorn said, “we’re still here.”

Silverhorn an interpreter and artist recently spoke at BGSU as part of the In the Round series which brings indigenous creators – filmmakers, writers, lawyers, musicians – to campus.

“Everybody heard about how we as native people were robbed, how much we lost,” he said. “You guys lost just as much.”

The people he grew up with are “awesome.”

“They are rich and diverse,” he said at the conclusion of his presentation. “They speak differently and act differently. Imagine what we could have done together in those 200 years.”

“I imagine my grandmother drifting off to sleep while the cicadas sing dreaming of what her grandchildren’s grandchildren would be doing with their lives. But what language did she dream in?

Talon Silverhorn

Native people are still here, and they have a lot to offer to the future.

They have always “science-based people,” though that was not in the Western sense, Silverhorn said.

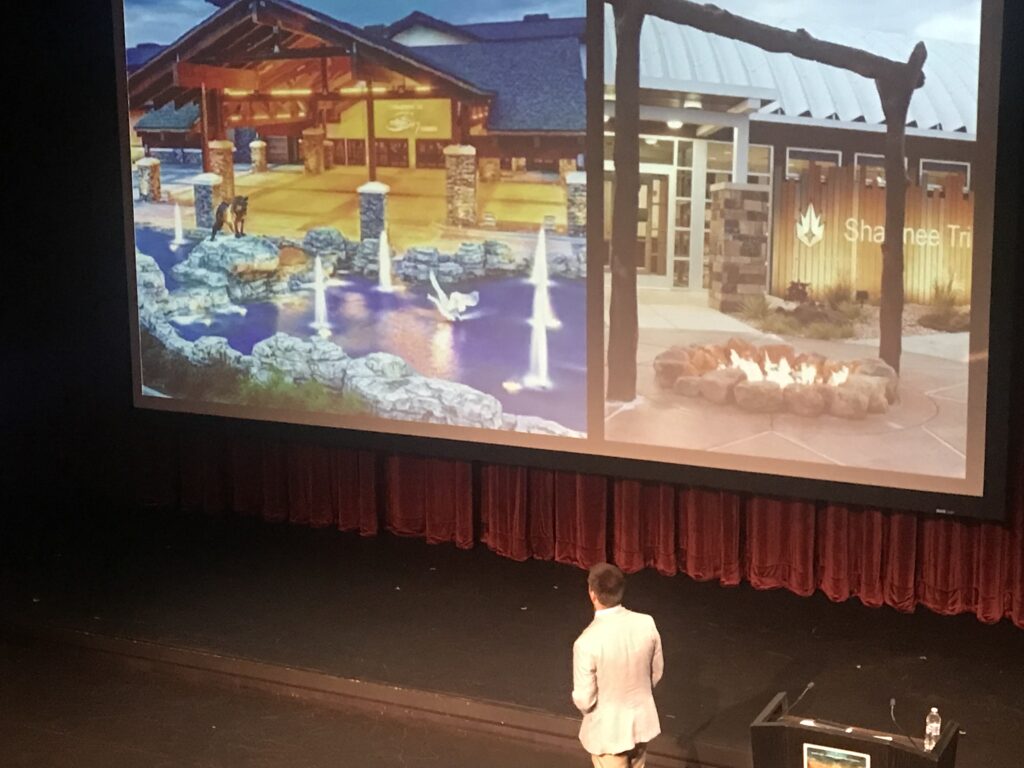

In Oklahoma, they build colleges, as well as teach in them. They work in digital technology. They build museum and cultural centers.

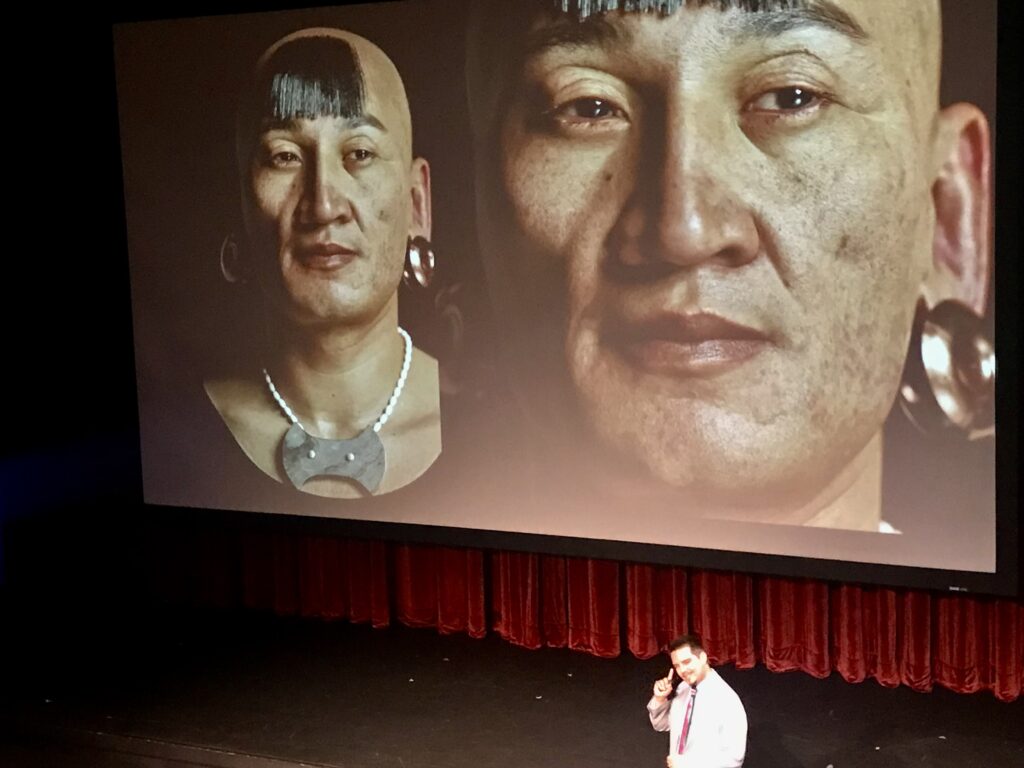

As an artist who creates images of his people and their artifacts, Silverhorn uses 3D technology. He learned by watching YouTube videos and creates using Blender.

He imagines bringing indigenous design and community together with technology – a wigwam home with solar panels.

Many people, though, think of indigenous people as history. That’s where Silverhorn and members of their family encounters them as historical interpreters.

Silverhorn read from an essay he wrote about being at the Hopewell Mounds.

“I imagine my grandmother drifting off to sleep while the cicadas sing dreaming of what her grandchildren’s grandchildren would be doing with their lives. But what language did she dream in? I have a feeling that when I close my eyes and imagine my ancestors, I see something very different from what others see. Is my vision more correct? I don’t know.

“How do we bring tribal and nontribal visitors to these sites to a more similar conclusion. And the answer I think is interpretation.”

The key to interpretation is to deepen people’s relationships to the people of and artifacts from the past.

Much interpretation was focused on war, battlefields, and military reenactors.

Silverhorn and his family have worked to “demilitarize” it. He showed a photo of them depicting a family caught in the crossfire of the frontier wars.

He talks about history because that’s why people come to the sites. But he strives “to take them by the hand and bring them where we are.”

He takes the questions people ask about his ancestors, and reframes them, so they ask about how his people live now.

It is important for this to be done by indigenous people themselves, not White interpreters who feel through their studies know more than contemporary native people.

Some native people, Silverhorn said, are reluctant to take on this role. They feel they are being asked to perform for strangers. He himself has been criticized for sharing his culture with outsiders.

“This is the community I know that’s why I do what I do.”

Silverhorn is interested not just in cultural preservation, but cultural advancement, taking what has been passed on to him and shaping the future.

“Culture is ours,” he said. “It doesn’t belong to our ancestors. They got to live their lives. Now it’s our turn.”