By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

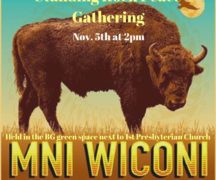

The standoff in Standing Rock, North Dakota, between Lakota and their allies from other Native American tribes is at once a continuation of the struggles between indigenous people and European settlers and their ancestors as well as a promise for a more sustainable future.

Anita Jane Britt, of Bowling Green, came back from a recent stay at the Sacred Stone camp on the Standing Rock reservation, convinced of this. “This is a historic gathering of 556 tribes. I believe this is really a pivotal point in our history. I believe this experience offers a lot of healing to people.”

Water protectors, Native Americans and their allies, have gathered to stop the Dakota Access Oil Pipeline going through native land, considered sacred. The pipeline would run under the Missouri River, where any break would pollute the water source of the Standing Rock Lakota.

Water protectors, Native Americans and their allies, have gathered to stop the Dakota Access Oil Pipeline going through native land, considered sacred. The pipeline would run under the Missouri River, where any break would pollute the water source of the Standing Rock Lakota.

Militarized security forces have arrayed against them.

Even as this confrontation continues plans for a more permanent center are underway. “As you kind of go throughout your day you see a whole community growing,” Britt said. An ecologically sustainable village is being built, including a kitchen, a straw bale school house and what is planned to be “the largest yurt village outside of Mongolia.”

Britt, 22, studied Native American history and literature at Bowling Green State University. A graduate of the School of Art, she studied printmaking. “My art work is largely research based and explores human connections to nature through emotions. Native American religion and mythology informs that very well.”

Family lore, she said, has it that there is a Seminole ancestor in her bloodline. This tie to Native Americans is common among those of Scotch-Irish ancestry from the Appalachia. It’s problematic since some settlers claimed native, usually Cherokee, blood so they could make land claims, she said. Sometimes the intermixing was a result of rape or forced marriage.

Britt was just returning from a stay in Taos Pueblo, New Mexico, when she heard about the action at Standing Rock. She went to Columbus to protest the state’s sending state troopers to assist the forces backing the pipeline company. While there she met two women who had collected supplies, and needed help delivering them. Britt volunteered.

She headed out on Election Day arrived the next morning and stayed until Sunday. “There’s something about the nature of this camp. It’s a vortex so many people from different time zones. The days really expanded.”

She stayed at the Sacred Stone camp. That area is not part of the direct actions, in which water protectors confront the pipeline forces, the DAPL military, as Britt refers to them.

The camp is a foundation of the action. From there donations are coordinated and supplies are divvied among the other camps. The sacred fires that burn elsewhere in the camp were lit with embers from the fire at Sacred Stone.

At that camp she found many children as well as elders and other “solitary travelers like myself.”

This as the place to acclimate herself to another way of life, another rhythm. She found an openness, honesty and generosity. All her contemporaries are brothers and sisters, the elders are all grandmother and grandfather, those between are uncle and auntie.

She moved around camp helping as she could. She delivered blankets to another camp. She helped make a barbecue dinner for the Morton County Sheriff’s on the other side of the river.

She used her printmaking skills to make banners for the protectors. Everything, even picking up trash, is considered an act of prayer.

The cardinal rule is no weapons and no drugs.

“The Water Protectors are peaceful, prayerful, and patient in the face of overwhelming ‘power’ and violence,” Britt said.

Though she did not participate in direct action, she witnessed the results. The bruises from rubber bullets and bean bags. The red eyes from being maced.

At night the pipeline security shines spotlights into the camp, and planes equipped with Stingray technology to monitor cell phones fly overhead.

“There’s so much going on it brings up a lot of emotions,” she said.

Britt said she suffers from depression, which has made it hard to reach out to other people, but at Sacred Stone she found it easy to open up.

As a survivor of sexual violence, she found the approach of the DAPL military to be similar to what she experienced. “I felt someone had the right to something that belonged to me, the same as these oil companies are saying we have the right and the aggressiveness and money and the anger to take what we think belongs to us. I think that’s a very aggressive attitude in our country.”

Those fears, she said, were only heightened as she drove toward Standing Rock through the night listening to election results.

Britt said that she understands some on the other side of the lines are just there for the paycheck, trying to support their families. But “some there to want to hurt someone,” she said. “They egg on protectors.” In return they may be greeted with an invitation to hug.

At night, join together around the fire to share songs, stories and prayers.

As visitors such as Britt return from Standing Rock they bring “embers” of the struggle.

“We’re going to see more and more of this people gathering to protect Mother Earth and to establish a more sustainable lifestyle,” she said.

That includes protecting resources close to home, including opposing the Nexus pipeline planned to run through a corner of Bowling Green near the water treatment plant.

Britt plans to return to Standing Rock early next year, and is open to taking part in a direct action. In the meantime, she hopes to gather supplies and spread the message. That includes a benefit for some time later in December.

Britt said that she strongly suggests donating funds to either the Sacred Stone Legal Defense Fund (https://fundrazr.com/d19fAf?ref=sh_25rPQa) or directly to the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe-Dakota Access Pipeline Donation Fund at standingrock.org.

She noted: “As winter draws closer, supplies such as blankets, heavy duty camping gear, medical supplies, warm clothes, wood stoves and the like to help protectors winterize their camps are vitally important. Those interested in donating supplies should go to sacredstonecamp.org to learn more about what is needed on camp.”

She will be collecting supplies to bring out, or supply donations can be sent to: Sacred Stone Camp P.O. Box 1011, Fort Yates, ND 58538.