By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

The universe is on view in downtown Toledo.

Or at least photographer Eric Zeigler’s vision of the universe, which includes:

- Galaxies of 100,000 stars, compressed into one small frame the size of a computer monitor.

- One of Pluto’s moons, the smear of light as good as anyone will likely ever see it.

- The rust on a meteorite in an image blown up 36-times its natural size.

- A computer image of neutrinos – subatomic particles so small 65 billion of them fit into a square centimeter – interacting.

The exhibit “Under Lying” is now on view at River House Arts, 425 Jefferson St. The exhibit is open through July 30. For hours call 419-441-4025. The show will be part of Art Loop on July 21.

The work, Zeigler explained, comes from his interest in astronomy that was sparked by a class he took at Bowling Green State University, where he earned a Bachelor’s of Fine Arts in Photography in 2008.

He’d been taking photos since his early teens, inspired by his grandfather. Above the television in his grandparents’ home was a landscape photo his grandfather had taken. And scattered around the house were copies of Popular Photography magazine. His grandfather, Zeigler said, was interested in optics, and during World War II maintained sights on bombers that flew missions over Germany.

Young Eric was fascinated by the data included in Popular Photography. What did the shutter speeds and aperture opening numbers mean? “I was totally addicted to figuring all this stuff out,” he said.

He set his family’s new digital camera on manual. That helped him understand shutter speed, but the optics weren’t advanced enough to really vary the depth of field much.

Then at about 16, a friend’s family gave him a film camera. It all clicked.

The son of a carpenter, who worked with his father, he first attended BGSU to study construction management. “That lasted one day.” Then architecture. Then, since he liked making furniture, he decided to try the School of Art. Zeigler discovered he could take a photography class. That’s when his interest took off. It led him to the San Francisco Art Institute for a Master’s of Fine Arts.

Though living on the West Coast the focus off his work remained rooted in Waterville.

“The Route 24 bypass coming through Waterville took a significant portion of my parents’ property,” Zeigler said. “So there was this idea that I needed to visualize and preserve what it looked like before the road came through.” In essence, he said, it pose the question: “How do you make things that are just a figment of your imagination?”

That body of work, “From the Middle of Nowhere,” shot over the span of more than three years, turned into his MFA thesis.

He further explore the concept of visualizing the intangible through a series of diptychs, “Still Photographs.”

Zeigler went through his archives. He spread hundreds of photographs of a variety of subjects out on the floor. From those he culled pairs that in some way resonated with one another. “I saw connections between them, the way the images that worked back and forth described this separate space,” he said.

Together they expressed something that alone they could not. One shows a dead seal on a beach, the other a stranded Bentley. “I found there was this vast darkness and hilarity I could portray, but it didn’t exist in the images.”

After “Still Photographs,” he said, “I was stymied for a while.”

“I sort of intimidated myself by how interesting some of those individual pictures could have been. It was a little difficult to think I could consistently keep repeating myself and still think I could make something new,” Zeigler said. “I felt I had like I’d finally become an extraordinarily competent photographer where I felt confident enough to go shoot anything and I could get an interesting picture out of practically nothing. So there was a lot less challenge.”

So he made fewer photographs. He worked on carpentry, making limited edition books of his work and other projects.

That included pursuing his interest in astronomy. “I started a long time ago trying to make work that was astronomically based,” he said. “I couldn’t quite figure it out. It was almost impossible to make an image that I couldn’t directly access.”

Then last July, Zeigler, 30, went to his computer first thing in the morning and up popped an image of Pluto taken by the New Horizons space craft.

It was low resolution, hardly better than what his family’s first digital camera could produce. Yet it was a marvel.

“Here was seen for the first time something we thought we knew so much about,” Zeigler said.

He downloaded it. Enlarged it. Stretched it. Later there came an image of one of Pluto’s moons, which even in the highest resolution is a smudge of light.

Instead of stalking the landscape looking for images, he “dredged the internet for information.” He found images or artifacts that promised to help give some sense of the universe beyond the reach of the eye.

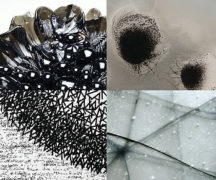

Those he manipulated and stripped of context. One is a NOAA satellite image depicting the phenomenon known as a “milky sea,” when the waters glow. “We still don’t know why it’s happening.”

He read a story of a sea captain who traveled for hours one night through the Indian Ocean as the waters shimmered. Yet no one had taken a photo. So Zeigler found the satellite image, blew it up, so it appears on first glance to be an abstract pattern of rectangles in varying shades of grey. In the middle the viewer can discern a salamander-like shape. That’s the milky sea.

Most of the images, including one of 100,000 dwarfs stars and another of a view that shows 50 light years and the birth and death of stars, Zeigler found and manipulated in some way. Almost all are in the public domain.

He’s also sought out objects on the internet, including a piece of a meteorite that fell on Texas in 1922. He brought it into the studio to photograph and then blew the image up to 36 times the object’s actual size, bringing into focus details not visible to the naked eye.

Zeigler also acquired a Manganese nodule, which he photographed. These rocks are found on ocean floor and are filled with rare earth minerals. “These rare earth minerals are the things that allow us to have our cell phones and other devices,” Zeigler said. “This very strange rock is the reason for the rest of the work.”

He also downloaded a 3D image of the 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko Comet. Printed it, and photographed it.

The images “suck the viewer” into the subject matter. Zeigler likens this work to that of commercial photographers working in advertising. “They take something that’s nothing and turn it into something that we lust after.”