By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

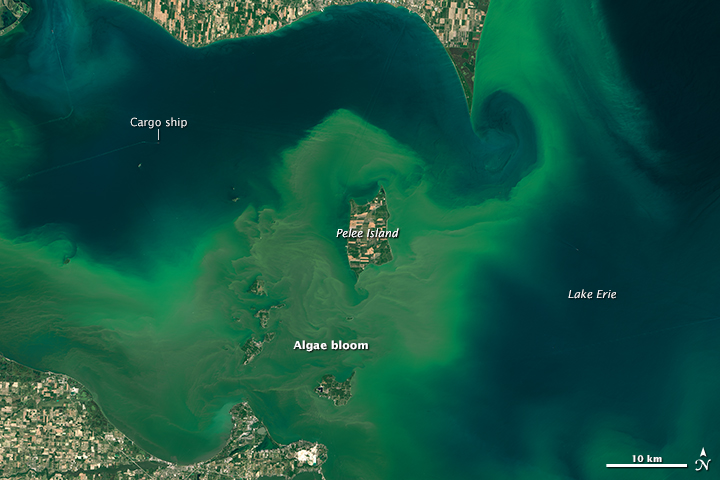

It’s been five years now since portions of Lake Erie turned to “green pea soup” and thousands of people in the region were advised to not use Toledo water for three days.

Since then, several steps have been taken to ensure that doesn’t happen again. However, the work is far from over, BGSU biologist George Bullerjahn told the Bowling Green League of Women Voters earlier this week.

Bullerjahn is one of the experts the region turned to in 2014 when the lake turned green. He is also one of the scientists who saw the problem emerging before it became a big enough crisis to get national notice.

“If you’re a scientist, we could see this coming,” Bullerjahn said, referring to a smaller harmful algal bloom in 2013 in Carroll Township, east of Toledo along the lake.

The algal bloom that hit in 2014 wasn’t huge – but it was “insanely toxic,” he explained.

Bullerjahn and others have been able to determine that a massive release of toxins from the blooms occurred over that weekend five years ago, so much that it could not be effectively handled by the chemical treatment at Toledo’s water plant.

For some residents of the region, that event eroded their confidence in local entities to properly treat water from the lake.

“There was a loss of public trust,” Bullerjahn said. “I still know people today who will only drink bottled water.”

But there seems to be a true desire to fix Lake Erie’s health.

“Water quality issues cross party lines,” Bullerjahn said. “I do think there is some momentum to change – at least in the Great Lakes.”

The Drinking Water Protection Act tasked the EPA with coming up with standards for toxin levels. And 47 members of the House – from both sides of the aisle – wrote President-elect Trump early in 2017 about the need for algal bloom research.

This region is not alone in watching its water turn to green goop. Lake Victoria in Kenya is suffering from sewage contamination, and Taihu in China is plagued by agricultural runoff.

Lake Okeechobee in Florida is far worse than Lake Erie – with 50 years of sediment in the water, he said.

“People from Florida call me all the time,” seeking his expertise on the issue and asking if they should sell their land in the area near Okeechobee. Bullerjahn politely explains he knows biology – not real estate.

In that region, large corporate farms are “driving the problem,” Bullerjahn said. And climate change contributes, with more rain causing more runoff.

But there seems to be some appetite in this region, he said, to prevent the harmful algal blooms from returning with such intensity to Lake Erie.

Those intentions led, last year, to Lake Erie being designated as “impaired.”

Bullerjahn was one of the experts assigned to figuring out exactly what that entailed. The scientists were given a box of doughnuts and coffee, and told to come up with a metric to declare the lake impaired and the metric to dismiss that designation if possible in the future, he said.

The standards require that Lake Erie have six consecutive years of healthy monitoring results before it can shed the designation.

Though some officials were fearful of the impact from the “impaired” declaration, Bullerjahn said the lake met the definition.

“A charter boat captain will tell you it’s impaired if he has to power up to get through,” he said.

To monitor the water, sensors have been deployed throughout the Great Lakes. Initially, the monitors were set up to warn water treatment plants of impending harmful algal blooms. But they do so much more – measuring the algal blooms’ behavior, their growth and decline, and their persistence. New data is collected every 20 minutes.

“Basically, we’ve hard-wired the lake,” Bullerjahn said.

Many efforts have also been taken to prevent the phosphorus and nitrogen, contributing to the harmful algal blooms, from ever reaching Lake Erie.

Studies have clearly attributed the bulk of the problem in the Lake Erie region to agricultural runoff. Sewage and lawn care chemicals can also contribute to the problem – but neither are a major factor here, Bullerjahn said.

So efforts have been made to divert nutrients from running off fields into ditches and streams, and ultimately making it to Lake Erie. Farmers are encouraged to preserve wetlands, install buffer strips, plant cover crops, inject fertilizer into the soil rather than spread on top, and time applications to avoid runoff, Bullerjahn said.

Studies have shown a need to reduce the nutrients entering the Maumee watershed waterways by at least 40 percent, he said.

But voluntary efforts by farmers appear to not be enough to hit that 40 percent.

The problem is going to require a link between science and policy, Bullerjahn said.

“Whatever we do is totally worthless,” unless it leads to policy, he said.

Bullerjahn also addressed questions about large dairy farms, known as CAFOs – concentrated animal feeding operations. He agreed they are “not adequately addressed by legislation.”

In addition to there being loopholes for CAFOs manure distribution, Bullerjahn said there are many smaller animal operations that slip past regulations. He is hoping the “impairment” designation for Lake Erie may lead to more regulations for those operations.