By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Like any army, those who struggled for freedom during the Civil Rights movement marched on their stomachs.

Food became an early symbol of the movement when five black college students took seats at a Woolworth lunch counter and waited in vain to be served while white onlookers pelted them with invective.

Food scholar Jessica Harris has looked at the menus of the lunch counters where the protests spread and noted that the bill of fare was hot dogs, hamburgers, grill cheese – typical “American” food.

Harris was the keynote speaker for the Beyond the Dream presentation Wednesday evening at Kobacker Hall in the Bowling Green State University campus.

Her talk “Feeding the Resistance: Deacon’s Chicken and Free Breakfasts” culminated an evening in which the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was celebrated in music, words, and art.

Uzee Brown narrates “New Morning for the World”

The program opened with Joseph Schwantner’s “New Morning for a New World: Daybreak of Freedom” performed by the Bowling Green Philharmonia conducted by Emily Freeman Brown.

The programmatic piece offered orchestral swells and whispers to accompany a text read by Uzee Brown, a BGSU gradate and now chair of the music department at Dr. King’s alma mater, Morehouse College. The text was drawn from various speeches and essays by Dr. King.

The music was anxious and on edge as Brown recounted the oppression of African Americans. “There comes a time when people get tired,” he intoned, “… tired of being kicked about by the brutal feet of oppression.”

There were brilliant brass calls to action as the text described the struggle for freedom. “Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood,” Brown read.

The piece ended reflecting on the future when “we will emerge … into the bright and glowing daybreak of freedom and justice for all God’s children.” The orchestra concluded quietly as the musicians hummed a simple, resonant harmony.

An abstract animated film by Heejoo Kim with music by Evan Williams, a BGSU graduate, and poetry by student Bea Fields scrawled across the screen was shown.

Then Harris spoke. In her 40-minute presentation, she rooted the Civil Rights Movement to the post-World War II period, when whites saw the beacon of hope while blacks in the south faced segregation and blacks in the north were left behind by white flight in deteriorating neighborhoods.

The various elements of the movement for black liberation had their own kitchen ways.

The church based movement in the south had church ladies who vied to serve Dr. King the tastiest traditional southern dishes. Activists met around kitchen tables laden with fried chicken, macaroni and cheese, freshly cooked – not canned or frozen – greens, okra, and an assortment of pies, including sweet potato, and various fruit cobblers.

The Nation of Islam adopted Muslim eating practices, including the banning “the swine,” but their culinary practices also reflected leader Elijah Muhammad’s own personal tastes. He inveighed against many of those traditional southern dishes as unhealthy. The movement had its signature dish, Harris said. Bean pies were often peddled along with the Nation of Islam’s newspaper Muhammad Speaks. Muhammad even wrote two books on “How To Eat To Live” spelling out his beliefs.

The Black Panthers, founded in 1966 in Oakland, California, to combat police brutality, were considered the number one threat to internal security by J. Edgar Hoover.

The Panthers had another side, Harris said. Before anyone spoke about food injustice or food deserts, they addressed the concern about people living in poor neighborhood having access to nutritious food, Harris said.

They started a free breakfast program for school children. Ironically the government that worked to crush the Panthers realized the wisdom of this effort, and now serves free breakfasts in schools, Harris said.

student Dynasty Long greets Jessica Harris following the scholar’s talk.

By the 1970s, food defined people as much as their choice of clothes and hair styles, she said. Afro-centric activists ate food drawn from the global community, particularly Africa and the Caribbean, and contemporary vegetarian cooking often with faux African names. The bourgeois adopted the same upwardly mobile cuisine that their white counterparts did, inspired by James Beard, Julia Child, and “The Galloping Gourmet.”

Restaurants also played an important role, Harris said. Several restaurants claimed to have cooked Dr. King’s favorite fried chicken.

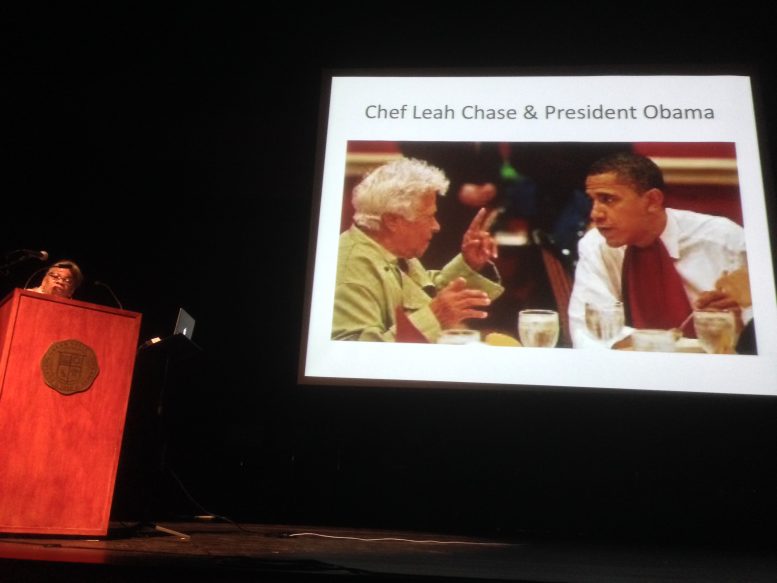

One New Orleans establishment, Dooky Chase’s Restaurant, played a seminal role in the movement. Leah Chase, whose in-laws founded the eatery, fed the Freedom Riders as they headed out through the South, offering them advice on what they would face. When they returned dirty and bruised, she’d send them around the corner to the home of the establishment’s bartender to shower. Then they’d return and she’d feed them.

The restaurant is still in operation and has hosted several presidents. Leah Chase, now 95, even scolded President Barack Obama for reaching for the hot sauce before he’d even tasted her food.

After her talk, Harris greeted well-wishers and signed books.

Students Dynasty Long from Detroit and Epiphany Thornton from Chicago were among those posing for photographs with the scholar.

Long said her mother is from the south. Harris’ discussion of the food prepared by church ladies and the competition among them rang true to the stories she’d heard at home.

Thornton said while they’d heard much about the Civil Rights movement, the talk shed more light on women’s role in the struggle.

It gave the students plenty of food for thought, she said, for the Women’s Studies papers they planned to write about the event.