By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Mummies have had many uses over the millennia – fertilizer, being ground for medicine, starring in horror films and kids cartoons, being the centerpiece for art museum collections.

The Toledo Museum of Art’s mummies were among its most popular attractions, and until now last viewed by the public in 2010.

The mummies, though, are not objects, said Brian Kennedy, the museum director. They are human remains. In all the hype surrounding ancient Egypt, that gets lost. A new exhibit “The Mummies: From Egypt to Toledo” aims to put that humanity at the center. The mummies – the remains of a Young Priest and an Old Man – are not treated as objects but on view in a darkened room, reminiscent of a wake. The exhibit continues through May 6. (Click for details o related events.)

Mummified Old Man

The museum’s exhibition designer, Claude Fixler said the remains are treated with “a much greater sense of reverence than in the past to bring home the point that these were someone’s child.

“They deserve the solitude of this space, a sense of quietude and meditation on their lives relating to our own in many ways.”

This is the third time Fixler has designed an exhibit featuring the remains.

Kennedy had just arrived in Toledo when that 2010 exhibit was about to be staged. Coming from Dartmouth College, an institution founded to educate Native Americans, and before that from the Australian National Museum where issues of the display of human remains were acute, he was bothered by some aspects of the exhibit.

He decided they would not be shown except in an exhibit where they can be put in context. Young Priest and Old Man had not been on exhibit other than special shows since 1997.

Curators Adam Levine, associate curator of ancient art, and Mike Deetsch, the director of education and engagement, were charged with providing that context.

Egypt had long fascinated Western culture. The goddess Isis was adopted by the Romans. When Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1795, he brought along hundreds of writers, scholars, scientists, and artists, Deetsch said.

Their work introduced ancient Egypt to the western world and gave rise to Egyptology. The Libbeys were among those fascinated, traveling to Egypt three times.

Levine said that 98 percent of what was acquired by the museum through 1906 was from Egypt. That includes the mummies of Young Priest and Old Man.

Levine said that 98 percent of what was acquired by the museum through 1906 was from Egypt. That includes the mummies of Young Priest and Old Man.

It was a different time, Kennedy noted, when it was acceptable to buy human remains. The Libbeys purchased them from Ralph Blanchard’s Egyptian Museum, right across the street from their hotel in Cairo, Deetsch said.

That story is told in the first room of the exhibit.

Egyptology gave way to Egyptomania after the opening of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922.

Suddenly all things Egyptian, or at least what was thought of as Egyptian in the popular imagination, were the rage.

There was jewelry, and glassware, and a touring magician Grover C. George from Zanesville who promised secrets from Egypt among his carload of wonders.

Tut’s timing was perfect for the mummy to become a movie star. The mystery and allure of the mummy is impossible for Hollywood to resist to this day. Deetsch said that because of “Goosebumps,” his 5-year-old thinks of mummies as something that will come after him in the night. Levine said his introduction to ancient Egypt was a “Scooby Do” episode.

Around the corner from where the trailer for Boris Karloff’s “The Mummy” plays in a loop, there is a placard explaining the origin tale for mummification. The story of how the goddess Isis bandaged together her husband, the god Osiris. This serves to introduce the viewer to Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife and how those influenced burial rituals.

As the visitors move through the exhibit, the rooms get narrower and the light more subdued until they reach the darkened chamber where the remains of Old Man and Young Priest lie in state.

Scans of the bodies before the 2010 show revealed them both to be male. One had been thought to be female because the coffin he was in was for a woman. But the dealer probably placed the mummy in the empty coffin with no regard to whether it was appropriate, Deetsch said.

Having the director of education so closely involved in designing the exhibit was important, Levine said. The exhibit “excavates notions of how we’ve come to feel about the exhibition of human remains.”

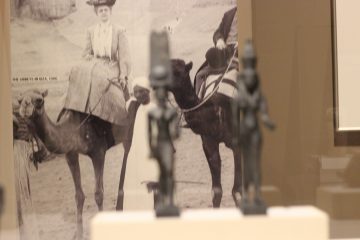

And after visitors pass by the iconic photo of the Libbeys mounted on camels during their voyage to Egypt in 1906, they will get the last word on what engages them most about ancient Egypt. Is it the history? The pop culture connections? The science? Or the ethical issue of how to treat ancient human remains?

The two people at the center of the exhibit, the Old Man and Young Priest, don’t get a vote.