By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Visitors to St. John’s Woods in Bowling Green will see plenty of birds and wild flowers, and deer, all within a majestic 60-acre stand of trees.

Visitor will see crows in a place was once touted as one of the largest crow rookeries in the country.

They won’t see “a wild man,” escaped from the circus nor sheep and pigs. And it’s unlikely the visitor will get lost, as did a man out for a stroll in the winter of 1896, on what are now well-marked trails in the preserve bordered by residential areas.

Yet these are all part of the history of Wintergarden/St. John’s Nature Preserve.

These stories and more can be found thanks to the Stories in the Woods project completed by students studying with Professor Amílcar Challú at Bowling Green State University.

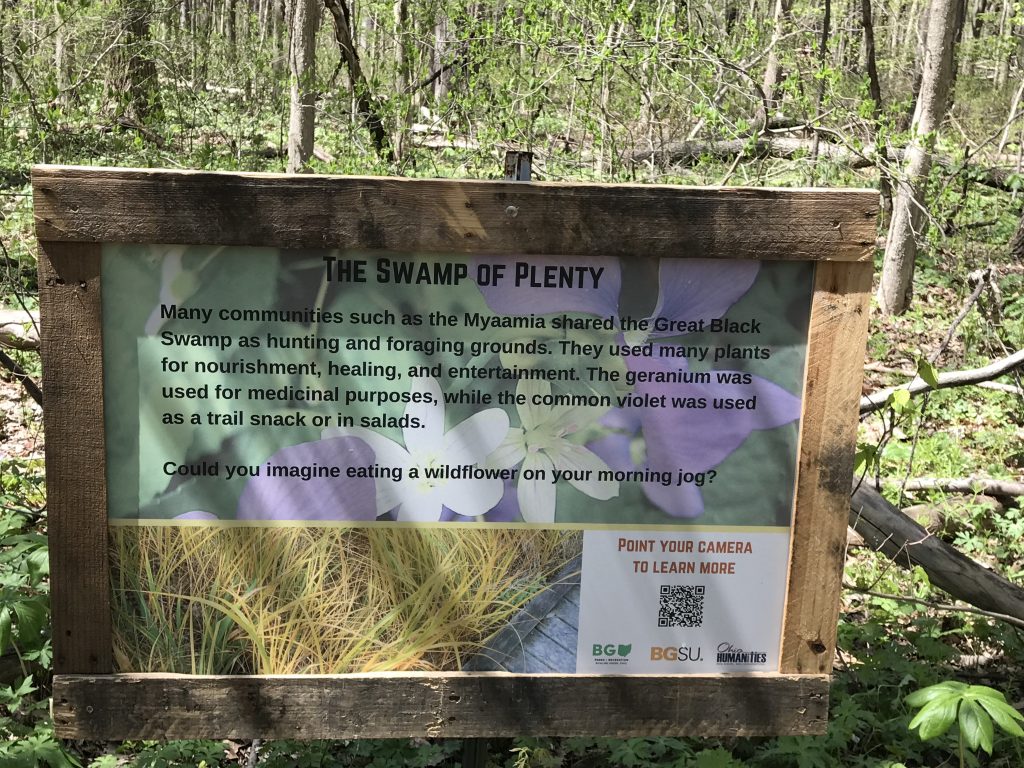

This spring the project erected nine signs along the green trail in the preserve. The signs tell the story from the time when the Ottawa and other indigenous people came to property to harvest crops for food and medicine to the period starting in 1842 when S.W. St. John and his family farmed in the area to the 1990s when efforts to preserve and restore its habitat began in earnest.

The project has its roots in Challú’s graduate seminar on environmental history. He had taught American Environmental history for seven years and brought a wealth of knowledge and resources to the seminar.

His goals for the class were both to provide overview of the literature in the field and an introduction to local environmental history. Beyond that he wanted the seminar to engage in a public history project that would have an impact on the community.

“This was a way to introduce the community to environmental history and their own environmental history,” said Addison Kennedy, an American Culture Studies graduate student, who has since graduated. “St John’s Woods is a local gem and we all love the area and thought it was beautiful and there’s already a lot of foot traffic there.”

So the class set off on a path that led them deep into the history of St. John’s Woods. Started in late 2019, the project was put on hold during the pandemic. The signs were erected in April and will remain on display through June. The website will stay up beyond that.

The idea to have a walking tour with signs was inspired in part by picture book story trails, Challú said.

They worked closely with park naturalist Cinda Stutzman and natural resource coordinator Chris Gajewicz, who provided a wealth of information. Still, Stutzman said, the students unearthed stories she’d not heard, such as the one about Zim Zim who ran away from Barnum’s Circus in Lima in 1904, and was located in the woods.

Madison Stump-Smith, who graduated from BGSU in spring 2020 and is now doing graduate studies in biology and wildlife management at the University of North Texas, said park naturalists confirmed that livestock had grazed in the woods because remnants of fences were found in the area.

They located T-posts as well. Those proved perfect for holding the information signs.

Rob Baither came up with the idea of making the signs from repurposed palettes. A social studies teacher at Waite High School in Toledo with a masters from BGSU, he used his woodworking skills to fashion the frames for the signs.

He said it was fitting to use the recycled wood in an environmental project.

Kennedy designed the signs. The frames gave the signs a “hand-made look,” and she wanted her design to complement that. She coordinated the colors with the locale’s natural hues.

Each sign has a QR code on it. All visitors have to do is point their phone cameras at the sign and the appropriate page on the website will pop up.

Challú said he was struck that as early as the 1890s the community recognized the woods as a distinct, wild place.

It was natural then that when the first Boy Scout troop started they came to camp and explore in the area. The St. John family, he said, attended the Methodist Episcopalian Church that sponsored that first troop.

The woods are by no means untouched. The plants that grow there reflect decades of livestock grazing. Those plants they liked to eat cannot be found, but those, like Jack-in-the-Pulpit that were bitter, continue the grow there.

The flora would have been much more varied when the Ottawa and other indigenous peoples visited and picked violets and geraniums both as food and medicine.

As part of the project, a webinar with Dani Tippman, Myaamia tribal plant tradition bearer and director of Whitley County Historical Museum in Indiana, was presented.

These were plants that would typically be considered weeds, Stump-Smith said. The indigenous people would pick them and eat them. “We’d never think of doing that today.”

A video of the webinar with contributions by Challú, Gajewicz, and Stutzman, can be viewed on the project’s website.

While the purpose of the project is to deepen local visitors’ understanding of the preserve and its history, it has also made a difference to the students who created it.

“One big part of it is just understanding the community I’m living in,” said Stump-Smith. “That helps me create a closer connection with the community, looking at what it was and what it is now, and all the people and efforts that were involved in changing Bowling Green into how it is. That made me feel like a close and important part of the community.”