By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

A telephone booth sits on the edge of Promenade Park in Toledo. Inside the telephone rings. When I pick up the ringer a woman is speaking in a language I don’t recognize, never mind understand.

She is in mid-statement. The passion in her voice pierces through the language barrier. When the translator comes on, I learn she is from Tibet, now living in New York City.

She fled Tibet because the Chinese killed her family. She has freedom now. “If I was living in Tibet, I wouldn’t have freedom.”

This is at once a voice from far away, yet speaking from the heart of America. The telephone booth is archaic, yet it gives voice to current concerns.

The booth and two others in located around Toledo are part of “Once Upon a Place,” an art installation created by Afghan-American artist Aman Mojadidi.

The telephone booths went up in Promenade Park, the library at the University of Toledo, and the main branch library of the Toledo-Lucas County Public Library several weeks ago and will remain in place through Oct. 22. The installation was displayed earlier this year in Times Square in New York City, where it was created.

Mojadidi recently spoke to students at the Bowling Green State University School of Art about the project, his life, and his career.

“What I was interested in with this project was to show how cities small and large, including Toledo, have been built by people who came from other countries,” he said.

Aman Mojadidi at BGSU

As the United States’ “flagship city,” New York seemed the place to bring that idea to fruition. Almost 37 percent of its population is foreign born as is about 12 percent of the nation’s population.

He started working on “Once Upon a Place” more than a year ago, just as the presidential campaign was heating up, and Donald Trump was stirring up his followers with anti-immigration rhetoric.

It was also when New York City was removing the last of its public phone booths.

Using a telephone booth involves “incredible intimacy,” Mojadidi said. People close themselves into the booth to converse. “It’s a full experience.”

“I was interested in all the stories told through these phones booths in the past and bringing them back to tell a new kind of story, immigrant stories.”

So Mojadidi traveled to different neighborhoods around the city, selecting those with the greatest diversity of immigrants. He reached out through synagogues, churches, mosques, and through labor and community groups. Mojadidi hung out in cafes and eavesdropped on conversations. He embedded himself into the communities, so he wasn’t just a stranger asking questions.

Then he sat down to record people’s stories of how they came to this country. It was not easy. “Immigrants were afraid,” he said, because of “the anti-immigrant xenophobia sprouting from the Trump campaign.

“I had a lot of rejection, a lot of people wanted to be anonymous.”

He didn’t approach them with a list of questions. “All I asked is to tell whatever it is you find most important about your immigration story,” he said. “I wanted people to speak from beginning to end without interruption.”

He had MP3 files of the stories imbedded into the telephones in the booths, and then set them out in the middle of Times Square. The timing of the installation brought it greater attention than it otherwise would have received. The Supreme Court had just upheld part of Trump’s proposed refugee ban.

He doubts the project will change anyone’s mind. “But it’s about providing a different narrative from what people hear,” Mojadidi said. “There’s a personal intimacy to those stories. You hear the individual, not the immigrant. You hear the struggles they’ve had, the reasons they came here. Many suffered persecution. They came to improve their lives.”

The installation was brought to Toledo by Contemporary Art Toledo.

“Once Upon a Place” is the most recent work in which Mojadidi considers his own biculturalism. In another work he described himself as “Afghan by blood, redneck by the grace of God.”

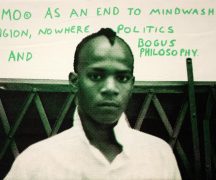

He was born in 1971 Aman Mojadidi to Afghan parents in Jacksonville, Florida, where he grew up and was taunted as a “sand nigger.”

He dropped out of high school. “I deplored the education forced on me,” he said. The history books glorified the Confederate Army and downplayed slavery.

Eventually he got his GED and went to community college where he studied anthropology and ethnography. After moving to California, he pursued graduate work in those areas, thinking they would help him to work with refugees.

Mojadidi told the students he took only one art course, in painting and failed.

But he was inspired by California artist Edward Kienholz who used found objects to make politically charged work. Mojadidi realized: “I want to do that. I want to collect junk and put it together in a way that tells a story.”

When he went to Afghanistan to do refugee work, he understood that instead he wanted to continue making art. Instead he used his training in anthropology and ethnography to create art.

From 2000 to 2013, he lived in Kabul. “Afghan by Blood, Redneck by the Grace of God” was created there.

He took photos of himself in the bazaar and other iconic locations sporting a ball cap and holding the Confederate stars and bars. It was a commentary on the Americans, many of whom reminded him of those back in Jacksonville, who were flooding the country to take high-paying jobs reconstructing the war-torn country. They did not leave their racist attitudes at home, Mojadidi said.

The artist now lives in Paris making a living not just from his art but writing chapters for books and consulting on films. He confessed he dreams of completing the book that resides on his laptop.

Its origins came after an editor approached him about writing a book about his return to Afghanistan. Many Afghani ex-patriots were writing similar books. Mojadidi had no interest. But he had a science fiction novel in mind.

He said he’s also been approached about doing a project similar to “Once Upon a Place” in Miami, telling immigrant stories from that community.

He finds these stories “humbling.”

“If I ever thought I had it tough in life, this put it in perspective,” he said. “Living in Afghanistan also added to that. … It’s kind of politicized me more. “

Many of today’s refugees are fleeing being bombed by Western nations. “It’s so easy now to bomb something because we can say we’re fighting terrorism. No one likes terrorism. … Something’s started, an unstoppable force of oppression.”

He told the students that traveling, and listening to people’s stories exposes him to the fundamental truths of the world and its people.

“For the sake of peace,” Mojadidi said, “people are always talking about how we’re all the same, we’re all human. But for me I say ‘no, that’s not the point.’ The point for me is that we’re all different, but it’s OK. That’s the way you get to world peace. … We’re not all the same, not from one culture to the next, not from one community to the next. But it’s OK. Not see the difference is something that’s scary.”