By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

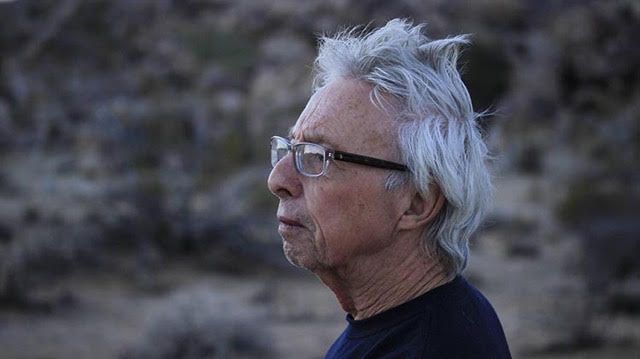

Composer Harold Budd said he was surprised when told his visit to Toledo would include a side trip to Bowling Green State University to talk with students.

He said he’s looking forward to the master class Friday, Oct. 5 at 10 a.m. in Kobacker Hall.

Asked what he’ll tell students, he replied: “The real truth is, it’s going to change. Whatever it is, wherever you are, it’ll change, and it’ll be better. Enjoy the ride.”

That optimism arises, the 82-year-old added, “against all odds, I would say.”

Budd, who has been active as a composer and performer for more than 50 years, will be in residence at the Toledo Museum of Art through Sunday, Oct. 7.

The highlight will be a premiere performance of his chamber piece “Petits Souffles” for string quartet including Brian Snow of the BGSU faculty on cello and the composer on celeste. The performance will be 8 p.m. Saturday in the Peristyle.

“I don’t really perform very often, in fact, at all,” he said in a recent telephone interview. “This will be kind of a new experience for me.”

Budd said that while the other parts of the ensemble are composed, his contributions will be improvised. He described his role as “modest … an occasional burst.”

The “Petits Souffles” like so much of his work is inspired by paintings.

A turning point for Budd came when he discovered in the 1960s the work of the color field painters Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell. That’s when what would be considered his style “blossomed inside of me.”

Yet, he said, he’s gone through various experiences musically and artistically, and “I gave them all up.”

He’s abandoned composition on two occasions, only to return. As he tells it, he has no choice. He’s not a performer, so this is what he does.

One enduring influence, Budd said, is the 19th century writer and illustrator Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whose work he reveres for being “overly romantic, overly decorative.”

“It can’t be too vulgar for me,” he said.

That from a musician whose work is marked by a shimmering simplicity with slowly unfolding melodies, music that is unhurried.

He’s collaborated with a range of producers and composers, from within and without the classical field, including Brian Eno. His work has been lumped in with ambient music, a categorization he eschews.

But back in 1959-1961 Budd collaborated with Albert Ayler, a free jazz saxophonist known for his volcanic sound.

They knew each other when they were in the same regimental Army band in Monterey, California. Budd played drums in the outfit.

He and Ayler would jam, often just the two of them. While these sessions were at first inspired by bebop, they moved far, far beyond. “It got away from that real fast.”

Budd remembers: “For a while that form of free jazz very much attracted me because of its impulsive nature, and I saw how rich that impulse could be. If you really bought that ticket, it was extraordinarily rich. I indulged myself in it. I learned a lot about trusting your instincts and not questioning them so much. You can go back and analyze them later. At the moment, it defies analysis.”

Monterey, he said, was “paradise.”

He even thought about re-enlisting so he could stay there, and Ayler encouraged him to do just that, so they could continued their explorations.

In the end, Budd said, he knew he had to leave. It was too boring. All paradise lends itself to is “self-indulgence.”

He remembers saying good bye to Ayler. He was driving away in his Mercury as Ayler was walking to lunch. “I had this terrible feeling. I knew I would regret it. And at my age, I still do.”

He remains a fan of that style of expressionistic free jazz, recalling fondly hearing Ayler’s contemporary Pharaoh Sanders in London. Sanders with his enormous sound was “a miraculous artist.”

He and Ayler came from the “Black spiritual impulse,” Budd said. “I knew I didn’t belong. I was just another guy who paid to get in. That was fine with me. That’s exactly what I was.”

He found that same spontaneity in painting and felt that worked better for him.

He was also drawn to composition after taking a course at Los Angeles City College in Medieval and Renaissance counterpoint. “I fell in love with that activity, yeah activity, except it was quiet and personal,” he said. “It was not musical in a way. It just range my bell. I continued in that direction.”

He’d found that jazz “where I originally entered music to begin with was not rich enough.”

“It wasn’t big enough, and it didn’t fulfill the other parts that I was just discovering. That’s what I brought me to composition.”

He studied the scores of the European masters, and then was drawn to the work of American composers Charles Ives and Aaron Copland. “I decided to go in that direction. I did. Of course I gave it up fairly pronto.”

Shortly after leaving the Army, he attended a lecture, “Where We Are Going, What We Are Doing,” by philosopher, composer, and writer John Cage.

“That’s where I’m going,” Budd said. “To hell with everything else.” He was “a snob.”

And he did go there, he said, “for a while.”

His love of visual art has been the constant. Asked about the trip to Toledo, he said he was looking forward to discovering the art museum, about which he’s heard glowing reports. He will give a gallery talk on Sunday at 3 p.m. in Gallery 1.

“Petits Souffles,” he explained, was inspired by French paintings all of which are “a little foggy, a little bit murky, a little flamboyant.”

The final movement is inspired by “Blue Balls” by American abstract expressionist painter Sam Francis “which is a very, very decorative, very handsome.”

“It doesn’t fit with my initial idea. Big deal. Just do it.”