By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

In the 1990s, Dr. Art Van Zee had questions about Purdue Pharma’s claim that there was only a slight chance of getting hooked on OxyContin.

The company claimed it was less than 1 percent.

Van Zee, who practiced in the heart of Appalachia, was seeing teenagers he’d immunized as babies now dying from overdoses as teenagers in the school library.

He saw farmers and coal miners getting hooked and losing everything.

One patient said: “This drug is my god.”

Van Zee knew more than 1 percent were getting hooked. What he was sensing were the early warning signs that OxyContin was leading to a much larger epidemic of addiction.

Van Zee is one of the heroes in Beth Macy’s best seller “Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America.”

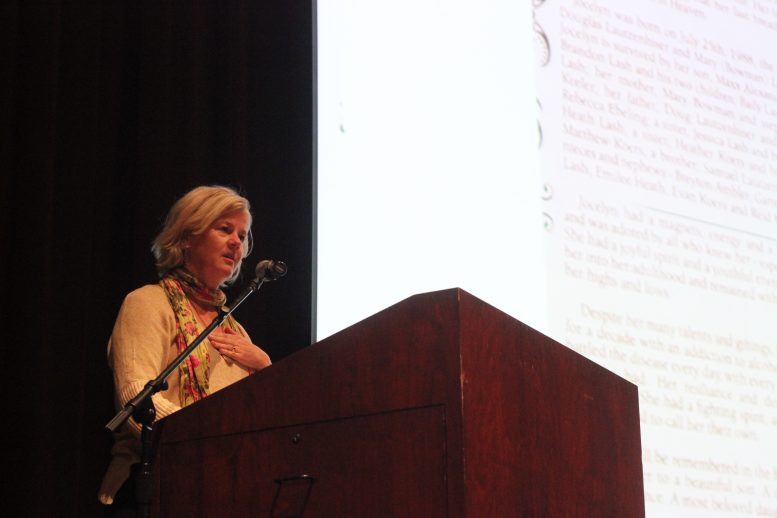

Macy told an audience of more than 200 in Bowling Green Performing Arts Center Monday night that she had to focus on people like Van Zee otherwise she may not have been able to finish the book.

She did complete “Dopesick,” which is a somber look at the opioid crisis from its beginnings with the introduction of what was touted as a wonder drug for pain relief.

OxyContin, Purdue said, had a time release formula that would prevent addiction. It didn’t take long for drug users to figure out that letting the coating dissolve in their mouth or that smashing the pill would instantaneously deliver a full dose.

It wasn’t until 2010 that Purdue addressed that problem, and by then, Macy said, it was too late. Heroin dealers were right there to fill the narcotic void.

The opioid epidemic sparked by OxyContin has reached across the nation. Wood County District Library Director Michael Penrod said as sad as it was to acknowledge it deeply affects the Bowling Green community. Macy’s talk was the first in a series sponsored by the library’s foundation.

At one point when researching the book, Macy questioned whether she could continue. The emotional toll was too great. As someone who had a family history of addiction going back four generations, she was concerned about getting depressed. Too many people she met were dying. Too many parents she interviewed were grieving. She’d gotten her advance from the publisher. Maybe she should just return it. But she couldn’t. “We’ve been living on the money.”

So she had to find the heroes in the story. Van Zee was one.

Another was 27-year-old Nikki King. The Indiana woman’s earliest memory was of her mother overdosing at a birthday party. King ended up starting a treatment program inside a courthouse to break down the barrier between the court system and recovery programs.

Macy had to concentrate on solutions.

Expanding Medicaid so those addicted could pay for treatment.

The promotion of medication-assisted treatment was another. Using drugs such as methadone, suboxone, and buprenorphine, to help those addicted to get off opioids is more effective than abstinence-only programs, like those promoted by AA and many faith-based organizations.

These medication-assisted therapies are up to 60 percent effective, while abstinence only, as best as can be determined, are 10 percent. Yet in some drug courts, abstinence only is what’s ordered.

Many doctors don’t seek the needed waivers from the Drug Enforcement Agency to offer the medicine. “They don’t want ‘drug addicts’ in their waiting rooms,” Macy said.

(During the discussion after the talk, Stephanie McGuire-Wise, of the Zepf Center, said that the local program offers all three medications to help ease patients off opioids.)

Macy spoke of Jordan “Joey” Gilbert who was making progress with medication assisted therapy. When he aged-out of coverage under his parents’ health insurance, he had to seek help at another, faith-based program, which wouldn’t allow him to take any drugs. He died at 27.

People may be on these medicines for the rest of their lives, Macy said, just as people suffering from diabetes have to take insulin for the rest of their lives. “Addiction is a chronic disease.”

A person can go eight years, and make three or four attempts at sobriety to get to one year of sobriety. Often they don’t make it.

For the first time in history, she said. Life expectancy in the United States is going down. That’s driven by deaths among white middle age men who’d never gone to college from overdoses, alcoholism, and suicide, — “diseases of despair.” A half-million people were dead who shouldn’t be, a Princeton University study found.

It was just that despair, Macy said, that Purdue Pharma capitalized on. Using prescription data, they targeted economically distressed areas where people were in real pain from lives spent mining, laboring in factories, and farming. The company knew which doctors were prescribing the most of their competitors’ products. That’s where they pitched their drugs. They treated doctors to trips. They gave them gifts. The doctors prescribed OxyContin to their patients.

Macy once asked a doctor at a party why he and his fellow physicians routinely prescribed a larger number of pills than necessary. Speaking under the influence of “the truth serum of beer,” he admitted, because they didn’t want to be bothered by calls on the weekend.

Tess Henry, then a teenager, went to urgent care for acute bronchitis. She got two 30-day prescriptions, one for a cough syrup with codeine, and another a pain killer that contained an opioid for sore throat. When she’d finished taking the drugs, she started to have diarrhea and felt nauseous. She didn’t know it , but she was feeling the results of withdrawal. She was dopesick. Through a connection at the restaurant where she worked, she got more pills.

This started a spiral downward. She had a son, and lost custody of that child because of her addiction. She’d been hooked for three years, when Macy met her in 2015.

She turned to prostitution and was homeless. She desperately wanted to kick the habit, and just when she was headed home to Virginia from Las Vegas for another attempt, she disappeared. A homeless man foraging in a dump found her body.

Macy wore a necklace that was given to her by Tess’ mother. On it were symbols of what she loved in a life, her son, poetry, rescue dogs, and the tree of life symbol. Tess had a tree of life tattooed on her back. That’s how they identified her body.