By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

James Jones, known on social media as Notorious Cree, took his charge to educate his audience about all things indigenous seriously when he visited BGSU recently as an In the Round series guest.

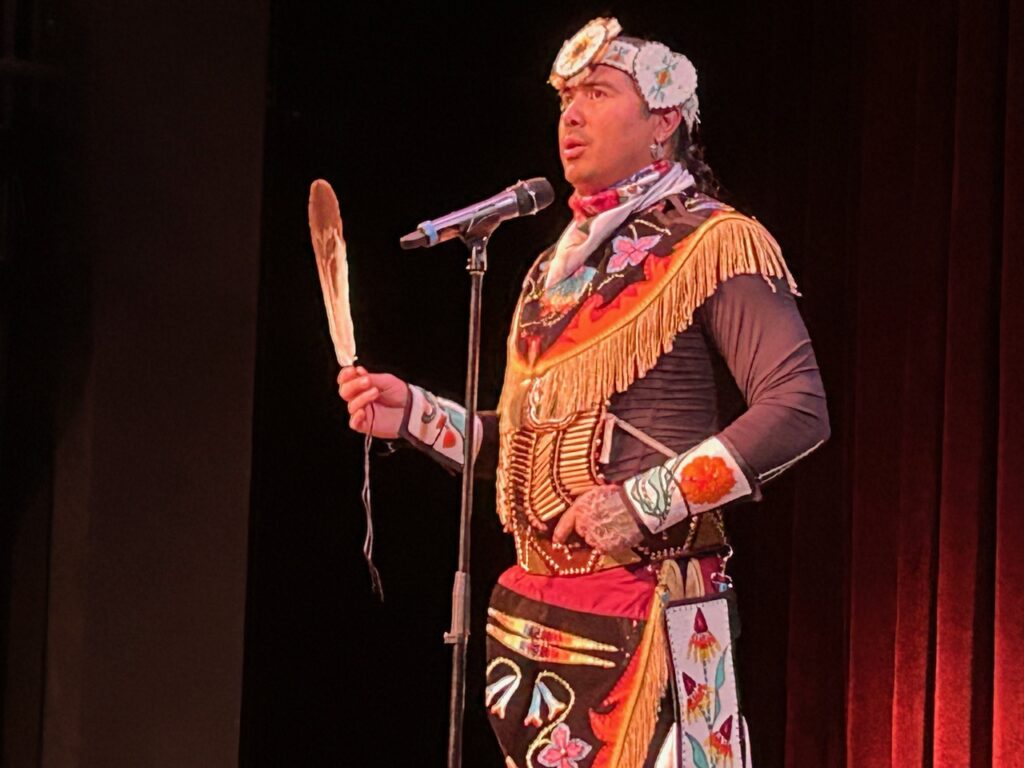

Coming on stage in full regalia, he announced himself in his native language as a member of the Nehigaw people, or people of the four directions, or Cree, the name given to them by the French.

Jones said he would teach those who filled the Donnell Theatre a word “sacred” to indigenous people. Jones carefully enunciated four syllables asking audience members to repeat each. Then he put them together. “A casino.”

Indigenous people are not as stoic and serious as movie stereotypes would have it, he said. Instead they believe laughter is medicine. As he delved into his journey to reconnect with his culture he touched on trauma and anger and recovery, but leavened them with humor.

Jones is a powwow dancer who has displayed his skills not just at indigenous gatherings but also at the Winter Olympics, Coachella, and on Canada’s TV show “So You Think You Can Dance.”

Though devoted to promoting and maintaining traditional Cree culture, he only started his journey as a teen.

“Growing up as a kid I never knew much about my culture,” he said. “My family was really affected by the residential school system. My parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles were taken away when they were children and put in residential schools.” There they were forbidden from speaking their language or practicing their culture. “They were not allowed to dance and sing,” Jones said. “A lot was lost, those traditions were lost, in those schools.”

But many in the younger generation, he said, set out to reclaim their past from the elders who had retained the culture. “A lot of us are reclaiming our ancestral knowledge,” Jones said.

His journey to becoming Notorious Cree began when he moved from the territory in northwest Alberta to the capital Edmonton.

He discovered dance there — not traditional dance, though. He joined a community of indigenous youth who break danced. They also attended powwows, where they experienced traditional dances.

Later while in New York he learned that early hip hop dancers had attended powwows and adopted steps they saw there. Those moves, the Apache and Indian step, are fundamental to the form.

Jones demonstrated the dances and music and talked about his regalia. When he played a song on flute, he said it had been used in courting.

Jones performed a hoop dance, with lighted hoops turning the dance into spinning, rhythmic light show.

Before he performed the chicken dance he told its origin tale.

A hunter came across a family of prairie chickens. Needing food, he killed and ate them.

That night the rooster appeared to the hunter in a dream. The chicken wanted to know why had the hunter killed his family? The hunter said he needed sustenance so he could find larger game to feed his family.

The chicken said that if the hunter promised to tell the story of the chicken, he would not kill him in the night.

The hunter agreed and that’s how humans learned the chicken dance.

Jones displayed an eagle feather that was part of his regalia. The feather was presented to him by an elder to honor Jones’ cultural work.

Jones said that’s why indigenous people find it offensive seeing someone at a music festival wearing a head dress. To indigenous people headdresses are akin to lifetime achievement awards, not just a costume.

Eagle feathers have deep meaning. Because the eagle flies so high it absorbs the love, sagietin, from the Great Spirit, and brings that down to Mother Earth, Jones said.

Jones said when he moved from his community to the city, he was adrift. He never felt much love when he lived in the city. He experienced racism, violence and substance abuse.

“I couldn’t truly love myself,” he sad.

About 10 years ago, an elder spoke to him, just “checking in on him.” The elder could feel the younger man’s anger and pain. That’s when the elder shared with him the teaching about the eagle and sagietin. While it was acceptable to feel that pain, the elder said, there comes a time when you have to just let it go.

The elder told Jones to “go home and think of those things those hurting just sending it love, send it sagietin, start telling yourself. ‘I love you.’”

Through that practice, Jones said, he found an emotional balance he had never had. And he shared that with others.

“Just like that eagle you can feel this,” he said. “We can find our way again. We can start supporting ourselves. We can find our lifeline, can find balance again,” he said. “Just like this feather, we are very, very resilient. We go through so many things. We can always come back to balance if we’re practicing that.”

Then Jones led the audience in a simple exercise to emphasize his point. He ask everyone in the Donnell to look at the person next to them and say: “Hey! I freakin’ love you man!”

Jones said he feels blessed and honored to be able to receive these teachings of his elders.

Another is the teaching about the two-legged tribe.

Jones said there was a time when he was young, he felt the sting of racism. He was bitter and angry, and didn’t feel he could trust people from other tribes and other ethnicities.

Then he learned that “we all come from the same tribe. We’re all from the two-legged tribe, the human tribe. The only way we will move forward is by loving each other and helping each other.”