By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Bravo! BGSU this weekend was a major arts event, showcasing some, but by no means all that transpires here culturally. Like the food served at Bravo! this was just a taste, delicious to be sure, but a sampling. As the spring semester unwinds, it’s hard to keep up with everything going on. Yet there are events that bear documenting.

“Emilie”

Among those performing at Bravo! BGSU was Hillary LaBonte, who with Caroline Kouma, reprised a duet from Mozart’s “Cosi Fan Tutte,” which was staged two weeks ago. That opera was a frothy entertainment.

Just a couple days before Bravo! though, LaBonte had the stage to herself in a very different opera.

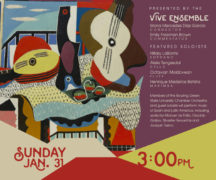

Maria Mercedes Diaz Garcia conducts the Vive! Ensemble during a rehearsal for “Emilie.”

Working with conductor Maria Mercedes Diaz Garcia and the Vive! Ensemble, which the conductor founded, she sang “Emilie,” a solo opera by Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho and Lebanese author Amin Maalouf.

Here LaBonte portrays leading 18th century French intellectual Emilie de Chatelet. We find de Chatelet in the process of writing a letter to her lover, the father of the child she carries. De Chatelet was a woman of great passions, both physical and intellectual, and all these weave together. She spills her heart into the letter.

Her quill is amplified so that there’s a telegraphic urgency as she writes. That’s just one of the ways the composer uses electronics to expose Emilie’s inner life.

Emilie is consumed by a sense of foreboding, about to give birth, she expects the worst. She speaks of her hopes for her child, hopes for a parent as loving and encouraging as her father.

Rare for the time, de Chatelet received a full education in the sciences and arts. She played harpsichord. The instrument electronically amplified plays a prominent part in the orchestra. It tracks, even anticipates, her thoughts. She is devoted to astronomy, physics, mathematics, and philosophy. There is nothing cold about her calculations and observations. They burn like the sun, whose constitution she ponders.

Emilie is at this point completing her translation into French from Latin of Newton’s “Principia.” This is the cutting edge science of the day, and still aligned with the mystical.

The score, performed by a small orchestra, amplifies the moods, whether the dark foreboding or antic excitement. LaBonte soars above, her voice capturing all the emotional shades of Emilie’s personality.

As she faces her fears that she will disappear in “the web of oblivion” she imagines holding her book, not her child, in her arms. As reality would have it, she died at 43, nine days after giving birth. Her completed manuscript would be found a few years after her death and only then published. It remains the definitive translation of “Principia” in French.

Emilie de Chatelet is something of a forgotten woman. This opera reveals her in all her complexity.

It’s says something about the passion Diaz Garcia, LaBonte, and their colleagues have for this opera, that they would tackle it in the midst of their own hectic spring performance schedules. The performance was a testament to the creative energy that surges through the new music scene.

“Montreal, White City”

Another troubled, passionate woman is at the heart of Bachir Bensaddek’s film “Montréal la Blanche (Montreal, White City).” In late March, the filmmaker visited campus to show and discuss the movie as part of “Exile and Migration,” a film series about displaced people that continues Thursdays and Fridays through April. (See schedule.)

Filmmaker Bachir Bensaddek answers questions following a screening of his film “Montreal, White City.”

As an Algerian who immigrated to Canada in 1992 to study film, Bansaddek knows about migration. But his transition was very easy, he said. He was a 19-year-old student. All he had to do was study film and hang out with his friends. It was a heady time in Montreal with the Parti Quebecois pushing for independence for the province of Quebec. Here was in a place searching for its identity. Bansaddek absorbed it all.

Back then there were about 4,000 Algerians in the city. A decade later there were 50,000. They had fled “the black decade” in Algeria, a time of terrorism during which 200,000 people died from bombings, massacres, and assassinations.

By then “after everyone knew that an Algerian was someone who said he was a doctor or engineer back in Algeria but drives cab now,” Bansaddek said.

When he interviewed his displaced countrymen for a documentary play, he found a very bitter community. They did not have the privileged experience that he’d had. They were middle-aged with families to feed and keep warm in Montreal’s bitter winter.

When he saw his play staged, he realized he needed to turn their stories into a feature film. Ten years later in 2017 he released “Montreal, White City.”

The title refers not only to Montreal in winter but to Algeria’s capital city, Algiers, traditionally known as the White City.

That captures the dichotomy at the heart of the movie. People caught between two worlds, the one their bodies live in, and the one that holds their spirits hostage.

Set on Christmas Eve, which happens in that year to occur during Ramadan, the Moslem month of fasting, we travel along with a cab driver Amokrane as he transports partiers throughout the city. Through the intervention of Santa Claus, or a man dressed as Santa Claus traveling from engagement to engagement, he ends up picking up a distraught yet glamorous woman. Kahina was a pop star in Algeria, but she was believed to have been killed.

For Amokrane this is like meeting a ghost. He is also struggling with his own memories of terror in Algeria. He works on Christmas Eve because the money is good though it keeps him from breaking the Ramadan fast with his young family. It helps him keep the memories of a tragic Ramadan at bay. He’s haunted by more than Kahina. He’s haunted by what happened to his parents and siblings back in Algeria.

The film is an odd emotional mix with people struggling just to keep alive, and yet with great comic moments. Interspersed throughout are clips of a quartet of musicians playing Christmas songs on traditional Algerian instruments.

The music offers a sense that maybe such divergent cultures can harmonize. The plot ends on a hopeful note that maybe the characters can at least inch toward a better life, if not escape the sadness that pervades their existence.